I recently ran a personal best at the Winschoten 50 km. In this blog, I cover the training between the 100 km del Passatore (end of May) and this race, which was far from what I had planned or expected, but gave me an opportunity to test a few things and keep enjoying experimenting with the art of training.

In particular, here I will focus on a few aspects that I hope can be interesting to others, or at least can give some food for thought:

The original plan and goals

Overtrained or not overtrained? using lactate and HRV to diagnose the situation

Making the most of the current abilities (or lack thereof)

3 weeks to get race ready: what did I lose, what do I need to improve and how can I get there?

Specificity, (lack of) tapering

The race

alright, let’s get to it.

The original plan and goals

Having raced a good 100 km at Passatore (training and race report here), and having gone through this already last year, finding myself in the best shape of my life right after the 100 km, I thought it’d be a similar kind of summer. Last year I went back into racing quickly and got injured, hence this year I thought I’d skip the racing and just keep building with training (sometimes we do learn from our mistakes). I planned to keep going with my recent non-linear periodization (see here), but focus a bit more on short workouts to get some speed back after the ultra (e.g. VO2max type of work).

However, after a few normal weeks post 100 km, I found it really hard to run. I’d be very sore in my quads the first few kilometers, then get somewhat better, and eventually be extremely fatigued after about an hour. Going from running 30 km with 1000m of elevation per day to running 50 km per week gave me a bit of an existential crisis.

Overtrained or not overtrained? using lactate and HRV to diagnose the situation

The timing of it all was also what made it confusing. After Passatore I had already trained quite well for 5 weeks. I took the first two weeks very easy, then slowly got back into structured training, and I was feeling good. At this point, the issues showed up, about 5-6 weeks after the race.

Given how hard running felt, and the major training block and race I had done, it is natural to think that maybe I did too much or that I was overtrained. I never take much of an off-season and tend to go by feel and see what I can do after major events. I keep moving at low intensities until it feels good again. However, this time something went wrong. To see if I could spot anything strange in my data (which might point to overtraining), I looked at and tried the following:

Non-training related energy levels: how did I feel e.g. at work or simply during the day?

Different training modalities: how would not running but e.g. cycling feel? A similar sense of fatigue could point to overtraining.

Abnormal physiological data: either a suppression or an increase in HRV outside of my normal range, and the same thing for exercise heart rate, or deviations in lactate measured at known intensity, could point to overtraining.

During those weeks, I felt good mentally. I had no fatigue during the day outside of running, I was sleeping fine, I was doing good work, and I was motivated to train. All good from this angle. I also picked up cycling again, and I could do intervals, I could do very long rides, I could train many hours per week on the bike, with no issues. Feeling good and performing well in cycling was in line with my physiological data, which did not highlight any issue either:

My subjective feel, the data, and my ability to train while cycling gave me confidence that I was alright, and my legs and muscles just needed some time to get back into proper running.

To further investigate running-specific issues I figured I could have a look also at potential differences in exercise heart rate and in lactate levels at known intensities. Basically, I wanted to look at two sides of the response: the cardiovascular response, using heart rate during exercise and HRV, and the metabolic response, using lactate at different intensities.

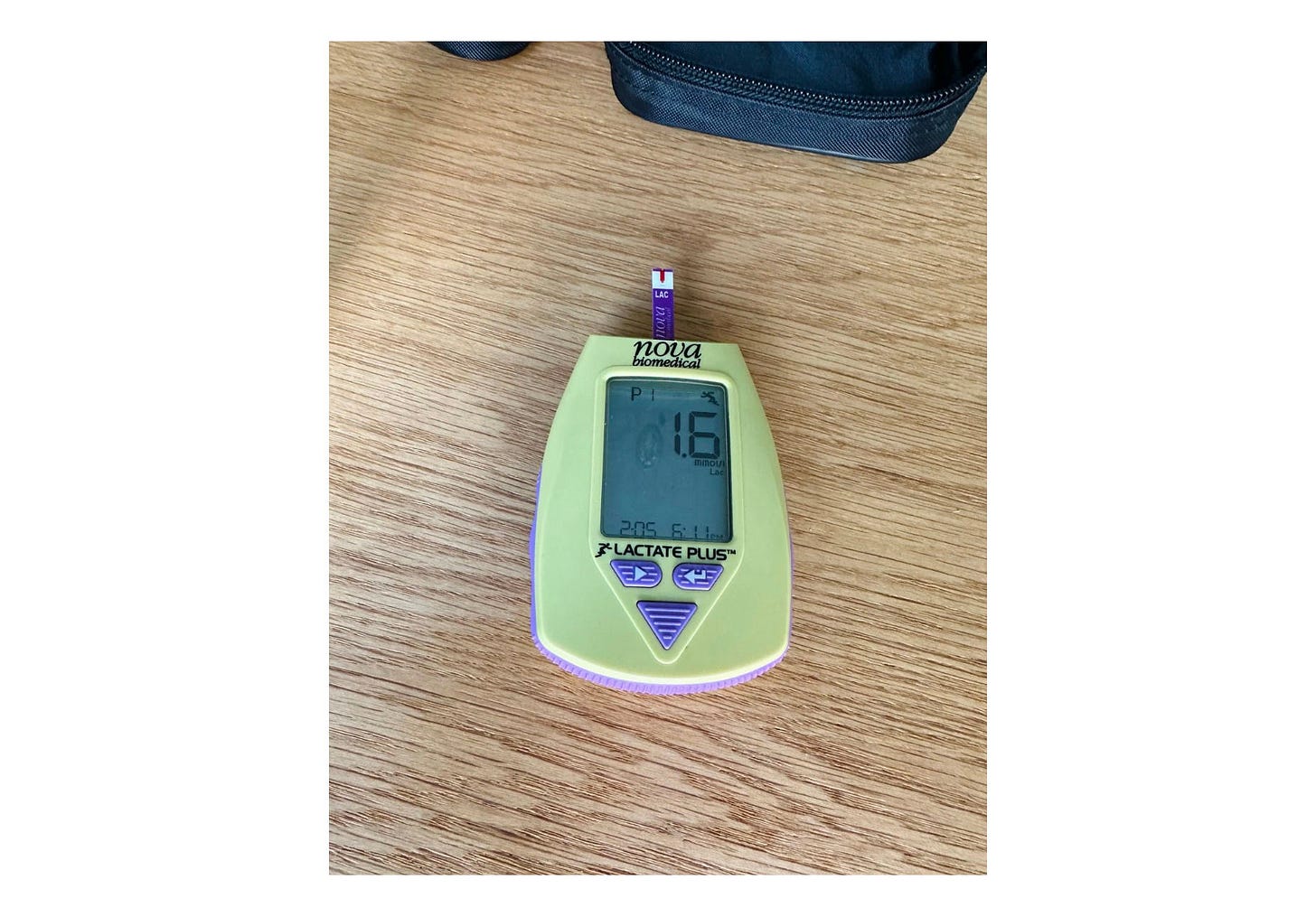

For practical reasons, I picked high-end zone 2 (in a 5-zone model) and near-maximal efforts to look at lactate, with the idea that either a particularly high value at high-end zone 2 (where I expected to be around 1.5 mmol/l, i.e. my first lactate threshold), or a particularly suppressed value after a near-maximal effort (e.g. a set of 800s on the track), could both point to some issue. Please see this blog to get more context around training zones, lactate, and so on.

As shown in the picture above, lactate levels when running near my first lactate threshold, or even in low-end heart rate zone 3, were pretty low and did not highlight issues. A potential issue here could be to see a very flat lactate profile across intensities, which could also be indicative of metabolic issues linked to overtraining. To test this I pushed hard on the track and tested there, reaching lactate levels similar to what I had seen in my best shape, after maximal tests in the lab (see here). Hence, I excluded this possibility. It was all fine from a metabolic point of view.

In terms of heart rate, I could see in training that it was slightly elevated at all intensities. I took this just as a sign of detraining. I was training less, and I wasn’t training well, hence my heart rate was slowly increasing at submaximal intensities, as expected. No large deviations or anything abnormal.

From all of this, I learned that I was okay, but my legs weren’t able to run the way I had been doing for the previous two years. I still had no idea why, but both my subjective feel and the data were helpful in finding some peace of mind and deciding how to move forward in terms of training. Had lactate been different, it would have prompted a different solution (for example, with higher lactate levels at low intensities, I would have moved to lower-intensity training).

In terms of running, at this point, I thought I just needed to be patient and give my muscles the time they needed to allow me to train well again.

My goal at this time was to devise the best possible training plan to limit running detraining.

Making the most of the current abilities (or lack thereof)

Last summer I had been injured for a while and experimented with cross-training and cycling for a few months, eventually maintaining cycling as part of my routine for most of the year (see here). Hence this year I had little doubt about the need to maintain the highest cycling volumes possible, and also added a weekly hard session on the bike.

In terms of running, given that I didn’t have any injury, and that I could not run for long, I opted for running little but running hard. This is typically how you can limit detraining over a period of a few weeks when you cannot run the typical (higher) volumes. Below is a typical week, with one or two hard running sessions, a few short easy runs, and lots of cycling:

During these weeks, I felt like I could maintain the running fitness I had, which was far from what I wanted, but at least was not further decreasing. For example, my hard sessions remained more or less the same, and I could over time increase the number of reps, running slightly slower:

I kept this going for a few weeks. I could run hard once in a while, but I did not force it. If I was feeling sore and fatigued in my legs, I would cycle instead.

Four weeks before the Winschoten 50 km I met a few friends that had also planned to race and mentioned I was probably not running. My legs weren’t feeling it. Until they did. A few days later I went for a longer run with friends and felt okay. The day after, instead of feeling super sore as it had been for the previous month, I felt good and ran intervals on the track. I had turned a corner. I do not have a clear view of what caused the issue or what made it go away, my best guess is that I simply needed the time after the 100 km, even if issues manifested themselves a bit later and I responded very differently from the previous year (a year in which the 100 km preparation and race execution had been extremely similar to this year).

By monitoring changes in training and physiology, and adjusting training accordingly, I was then ready to resume running training.

The next question was how to best prepare for the Winschoten 50 km in the 3 remaining weeks.

Three weeks to get race ready: what did I lose, what do I need to improve and how can I get there?

It’s one month to race day, and considering there’s not much you can do on race week (even though I did try something on race week too, see later), I had about 3 weeks to use to get race-ready.

In this period of running detraining, I had mostly lost my speed (last year I ran a 17’ 51” parkrun in summer after the 100 km while this year I could barely run below 20 minutes) and durability (I couldn’t run long without feeling very fatigued after 2 hours).

Three weeks it’s a short time but I figured the best way to address the situation was to do a mini-periodization that would go from generic to specific, just like I’d do over a much longer time period before an ultra.

For the 50 km, I wanted to run just around the first lactate threshold or slightly above, at low-end zone 3 in terms of heart rate. At the moment, I couldn’t run hard and long, and therefore I started by running hard for short intervals and very long but at a slow pace and intensity.

I kept doing 800m reps on the track, 5 km progressions at parkrun, then run on trails for 4-5 hours. By the second of the three weeks, I started getting more specific and testing race pace, running 30 km around the first lactate threshold. I then added more sessions around this pace as I got closer to the race. Eventually, I ran 6 days / week, about 130 km / week. The week before the race, I preferred to keep going harder than race pace, to gain fitness, and went for another set of 800s on the track (the quickest session of all summer, which also gave me confidence) plus a set of 3 km reps a few days later. On race week, I went for 25 km at race pace four days before the race. Maybe a bit of a stretch, but I figured the intensity was low enough that I could make a full recovery by Saturday (race day).

During this phase of increased load, I reduced cycling to about two sessions per week: a longer ride the day I did not run (I run 6 days per week), and one session of intervals on the bike, typically the same day I’d do a hard running workout in the morning, or the following day. The idea was to keep boosting my fitness while limiting injury risk, and therefore using the bike for an extra quality session.

Once again I used HRV to see how I was responding to this phase in which both intensity and duration of training were increasing. Overall, I had a good response, meaning a stable baseline HRV, well within my normal range. I could also see the impact of my double quality sessions, which often led to acutely suppressed HRV just for one day:

Had the data looked differently, e.g. with a suppression in HRV when picking up training, I would have probably skipped the race, as it would have been a sign that I needed more time to get back where I was. Subjective feel would have played a major role in this decision of course, but in my experience, data and subjective feel tend to be well aligned in the medium and long term, as they were here. Despite more than doubling my running training load over a few weeks, I was feeling fine and the data reflected a positive adaptation and the opportunity to push hard for a few weeks and race.

Specificity, (lack of) tapering

A few more words about specificity. As I was getting closer to the race, ideally I would have proceeded with a marathon-like type of training, e.g. long runs with most of it at marathon pace. I think those sessions are great training for a 50 km race as the intensity and pace are quite a bit lower in the race. However, I didn’t have the fitness and durability to try something like my typical marathon workouts. Hence, I decided to prioritize 50 km race pace, therefore training near the first lactate threshold (high-end zone 2 instead of zone 3), which I could now do again as I was feeling better (high-end zone 2 is a demanding intensity, but in my experience, there is a large difference with marathon pace / intensity - see this blog).

I don’t test lactate often, but for this specific race, it was quite useful. For example, once I saw through testing that I was still well within the limits of the first lactate threshold even when heart rate was at 85% of my max, I was a bit surprised but It was useful information to know because if I had higher lactate values, it would have prompted more easy training, or reduced race pace, but since lactate remained low, I thought maybe I had a shot at running a personal best despite everything. Maintaining very high training loads for the last two years probably allowed me to still be metabolically fit even though I was losing some cardiorespiratory fitness. For this race, lactate was actionable information, even though the limiter is always heart rate, not lactate (i.e. if my heart rate increases because of drift, the heat, or poor durability, it is quite irrelevant if lactate stays low, I would still be unable to complete the race or maintain race pace. A low lactate at race pace was a necessary but not sufficient condition to race at that given pace).

Below we can see how the training intensity distribution has changed over the summer, with a shifted focus on specificity:

and here is a similar view where we can also look at the distance of individual workouts, with long runs finally re-appearing, even if at a slow pace and low intensity:

Both images are part of the Training Intensity feature in HRV4Training Pro, which you can try here if you already use the HRV4Training app.

Talking about cardiorespiratory fitness, my heart rate at any given pace was reducing quite quickly over these last three weeks of proper training, something that was picked up by HRV4Training’s VO2max estimate:

The estimate relies mostly on the ratio between heart rate and pace, and therefore if we hold constant a few important parameters (e.g. elevation and temperature), it can track changes in cardiorespiratory fitness quite well. In a few weeks, the estimate goes from 56 to 59 ml/kg/min, simply reflecting how I went from a state of detraining to better fitness. It’s always easier (and faster) to get back where we were, than to build fitness for the first time, hence nothing odd here.

In terms of tapering, I normally do not make any changes in training apart from reducing the duration or intensity of a long run 7 days before the race and reducing the duration of a hard session (assuming I’m recovered enough to do one) on race week. The three days before the race, I do very little, typically 1 hour or 45 minutes easy, each day, and the day before the race I run 30 minutes with a few strides at the end (what I call a mini-taper in the image above). No other changes.

For this race, I cut back even less as I did the two hardest sessions and one of the longest runs on the week before the race, and then ran also 25 km at race pace on race week. Personally, I prefer to keep recovery as part of the weekly equation, and avoid digging holes and then hoping to get out of them with 3-4 weeks of tapering. Very small adjustments in the last week or two will do, if we train in a more sustainable way, and manage intensity well, especially in our easy runs. Or at least, those are my current thoughts.

The race

The Winschoten 50 km is a road ultra on a flat, fast course, structured in loops of 10 km. It’s a good setup for a personal best, very well organized, and despite not being a fan of running in loops, it’s an event I look forward to.

This year the race was also valid as the Dutch National Championship over the 50 km and 100 km.

Weather

Perfect conditions at the start (10C, no wind), then it got a bit warmer and windy during the race (maybe up to 17C). Nothing unbearable like last year (up to 30 C).

Fueling

It took me a while to figure out fueling for an ultra. I tried real food, engineered food (energy bars, powders), gels, all of the above mixed up and at different frequencies. I have something that works well now and I used the same protocol but with a slightly lower intake as I couldn’t practice much over the summer and I wanted to limit nausea, which is rather frequent for me when racing. Eventually, I had 1 gel every 7 km (instead of the usual 6 km). I had oatmeal for breakfast, 3 hours before the race and 7 gels total, one before the race, and six during the race. I had two gels with caffeine (100 mg each, at km 14 and 35). I find gels with caffeine quite essential to get me clear-headed when fatigue starts to creep in, even though they don’t feel the same since I started drinking coffee again. I also had a sodium pill (200mg) with each gel.

I do not know exactly how much water I drank, as I took a sip at most opportunities on the course.

Pacing

I planned to pace my race based on heart rate (and of course perceived exertion). Based on the past years of training and racing, I know I can race a marathon with a cap of 158-160 bpm (see my blog on finding marathon intensity, here), and a 100 km with a cap of approximately 140-145 bpm. A 50 km for me is raced mostly at the very high end of zone 2, slipping into zone 3 at times. The idea was to then keep the heart rate around 145 bpm or a bit higher for the first lap, then up to 150 for the second, and then don’t bother with it unless it was really getting towards marathon heart rate too soon.

Given very recent training (like, the previous week), I decided to give it a shot for a sub 3h 50’ attempt. During the race, I felt like I almost had the fitness but I didn’t have the legs (as expected given how summer training went). It was very hard physically and mentally in the second half of the race, but I hung in there and eventually, I slowed down but didn’t lose much time, closing in 3h 54’, a few minutes better than last year.

I probably started a bit too quickly for my current fitness, but it felt good and rather effortless, while my heart rate remained in line with what I had planned. I stayed with the first woman for a few kilometers but the pace was unsustainable for me, hence I adjusted quickly and ran the remaining 46 km by myself, which was rather boring honestly.

Even accounting for a bit of normal fatigue plus the increase in temperature, I slowed down more than I recently did, while my heart rate increased more than it should have, which shows durability was still an issue (as expected). I had trained well only 3 weeks after all. In the table above I also added a column showing the increase of heart rate over speed, a marker of aerobic efficiency that captures how I am drifting in terms of heart rate, and slowing down in terms of pace. Again, lack of durability due to suboptimal training.

Putting things in perspective, I was happy with the effort, taking it as a good step towards future goals, as I keep building fitness and durability for long events.

Takeaways

In this post, I covered my preparation for the Winschoten 50 km, which led to a personal best despite an unexpected training period.

After a strong race at Passatore, I faced difficulties with running, which led me to question whether I was overtrained. By using a combination of HRV and lactate data, I was able to confirm that I wasn’t overtrained, but simply needed more time to get back to running. During this time, I relied heavily on cycling volume and short, intense running sessions to maintain fitness.

With only three weeks to prepare for Winschoten, I focused on rebuilding speed and durability through a mini-periodization, gradually increasing the specificity of my training.

Despite the challenges, this training cycle has given me valuable insights into my physiology and limits and has set the foundation for the next months of training. It’s all about the process after all.

Thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

What are your thoughts on the new algorithm for estimating thresholds, namely what was released recently by Suunto, using a dynamic DFA with HRV? You have shown that hard values don't work (eg. 0.75 for everyone), but this new approach seems promising. There's a video on YT from Suunto that goes into some detail in case you haven't heard about it yet (I doubt it 😃).

Hello Marco, Regarding nutrition, I was quite surprised by the news that some gel manufacturers declare a certain amount of carbohydrates that in reality are not there. Thanks for your post, very interesting!

https://www.irunfar.com/spring-energy-awesome-sauce-gel-controversy-lab-results