[TrainingTalk] 100 km del Passatore: Training and Race Report (2024)

Finish time: 9h 25'. Overall ranking: 67th / 3500

Last Saturday I raced the 100 km del Passatore (Strava activity here), a race I have been obsessed with for a long time (and wasn’t able to finish in my previous attempt).

I finished in 9 hours and 25 minutes, more or less in line with an ideal race scenario, ranking 67th of about 3500 runners. It wasn’t all smooth sailing, but we’ll get to that later.

It was quite a day, and as I write these words I am both tired and elated.

In this blog, I cover the training (including a high-level overview of the past few years, as well as more details on volume, intensity, specificity, hills, heat acclimation, long runs, and takeaways) and race (what I had planned vs how I executed, difficulties and learnings in terms of pacing, fueling and hydration).

Thank you for reading!

Outline

Background

The Race

My Journey

The Training

Volume and Intensity

Specificity: Hills and Heat

Hills: workouts

Hills: specificity

Passive heat acclimation

The Long Runs

Training Takeaways

The Race

Planned vs Executed

Pacing

Fueling

Hydration

Race Takeaways

Background

The Race

The 100 km del Passatore is the oldest ultramarathon in Italy, which goes from Florence to Faenza. I am drawn to this race mostly because of my personal history. I have lived not far from the finish line for 25 years, before emigrating to the Netherlands first and the States later. My father ran it 47 years ago, it was the second edition. As a child, I used to go with him to see his friends competing for a top-10 finish. I have many memories of evenings and nights spent between Marradi and Faenza, supporting runners battling this somewhat crazy challenge. If you were born here, you know the race (people here call it ‘la cento’, which means ‘the one hundred’, like there is no other). The heat, the hills, the 100 km. It’s special. As of this year, I even moved to the course, in Brisighella.

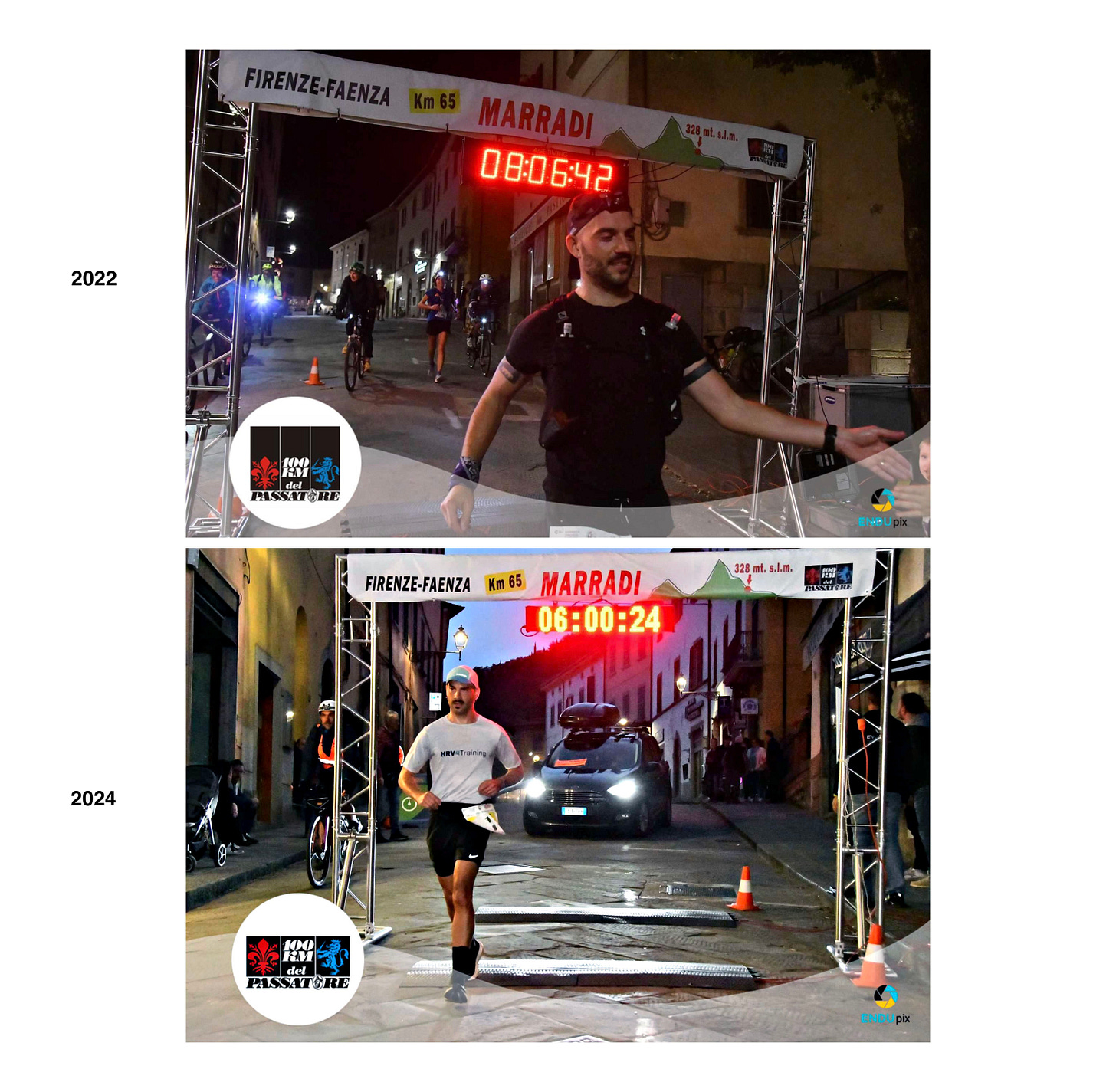

As my love for the sport kept growing over the years, I finally signed up and decided to give it a go two years ago, in 2022. Eventually, I had a rough day in the heat and ended up in a hospital with massive cramps (DNF). This forced break triggered some self-reflection and renewed interest in trying to get back into a different type of training and shape, as well as to address a few things differently, as I made some novice mistakes back then. Last year, I trained very well and got as fit as I could possibly be. I ran personal bests on every distance from the 5 km to the marathon, but Passatore was canceled due to major floods and landslides that hit our region just two weeks before the race.

Eventually, I did find another race two weeks later and ran a good 100 km in the night in Switzerland at the Bieler Lauftage (race report here), but you know, it is not the same thing. This year, Passatore was back, and I wanted to be as ready as I could, to finally cross the finish line in Faenza.

My running journey

When I was in high school, our physical education teacher would corner me and ask how much I'd been smoking, given my complete lack of endurance. I never smoked, but that’s how good I was as an endurance athlete, despite being active and doing sports since a very young age.

Many years later I fell in love with running. I left my country in 2009, when I was 25 years old, and started pouring myself into work, finding in running a much-needed break for my mental health, more than anything else. It wasn’t love at first sight, but I slowly started to enjoy it more and more.

After making some initial progress, I settled into middle-of-the-pack performance for the half-marathon distance (1h 45’ or so). As my work brought me closer and closer to the science of exercise and performance, I started to learn more about training and made some adjustments that led to large performance improvements. This year, at ~40 years old, I ran a half marathon personal best in 1h 20’. We are not breaking any records here, but it’s all about training, applying the science, experimenting, and seeing where we get despite obvious genetic limits.

See also:

The Training

Volume and Intensity

During my first preparation for Passatore two years ago, I was obsessed with volume. Probably, a naive mistake of first-timers at such a long distance, which can feel intimidating. I ran very consistently, 6 days per week, 130-140 km per week, for many months. However, I was also getting slower and slower, accumulating niggles, and being unable to do proper workouts or feel good at the end of long runs.

Last year, I still wanted to keep up a decent volume, as I know I benefit from it, but without sacrificing the intensity. It was clear at this point that just running more easy miles wasn’t working for me, and that more isn’t always better (a hard concept to get behind at times). In other words, I needed to focus on fitness before (maximizing) volume.

Both volume and intensity matter, but I find it easier to accumulate volume (you just have to run after all), while intensity requires adequate health, planning, recovery, etc. - and is the first thing to go when we have a setback. In the past two years I tried to make sure I wasn’t slipping, maintaining intensity, and staying healthy.

My periodization has changed in an attempt to prevent physical issues while allowing me to train properly. For example, while last year I’d do big blocks of a specific stimulus (e.g. a VO2max block, then a threshold block, etc.) now I keep doing a bit of everything, without overdoing anything. An example could be to aim for 2-3 workouts over two weeks, e.g. a threshold session (long intervals), a VO2max session (short intervals) and a longer tempo run (e.g. 10-25 km near marathon pace). This is what I do these days, with some adjustments depending on upcoming events.

As the days (and years!) go by and we stay consistent with training, it becomes easier to focus on fitness while also running high volumes. While two years ago it was all about volume, and last year it was all about fitness, this year I was able to stay fit (i.e. maintain intensity) while also running high volume. I wouldn't be surprised if in the next 2-4 years these numbers went up a bit more: it is just consistency, patience, and doing what our body allows us to do, which tends to be more and more if we manage to stay healthy.

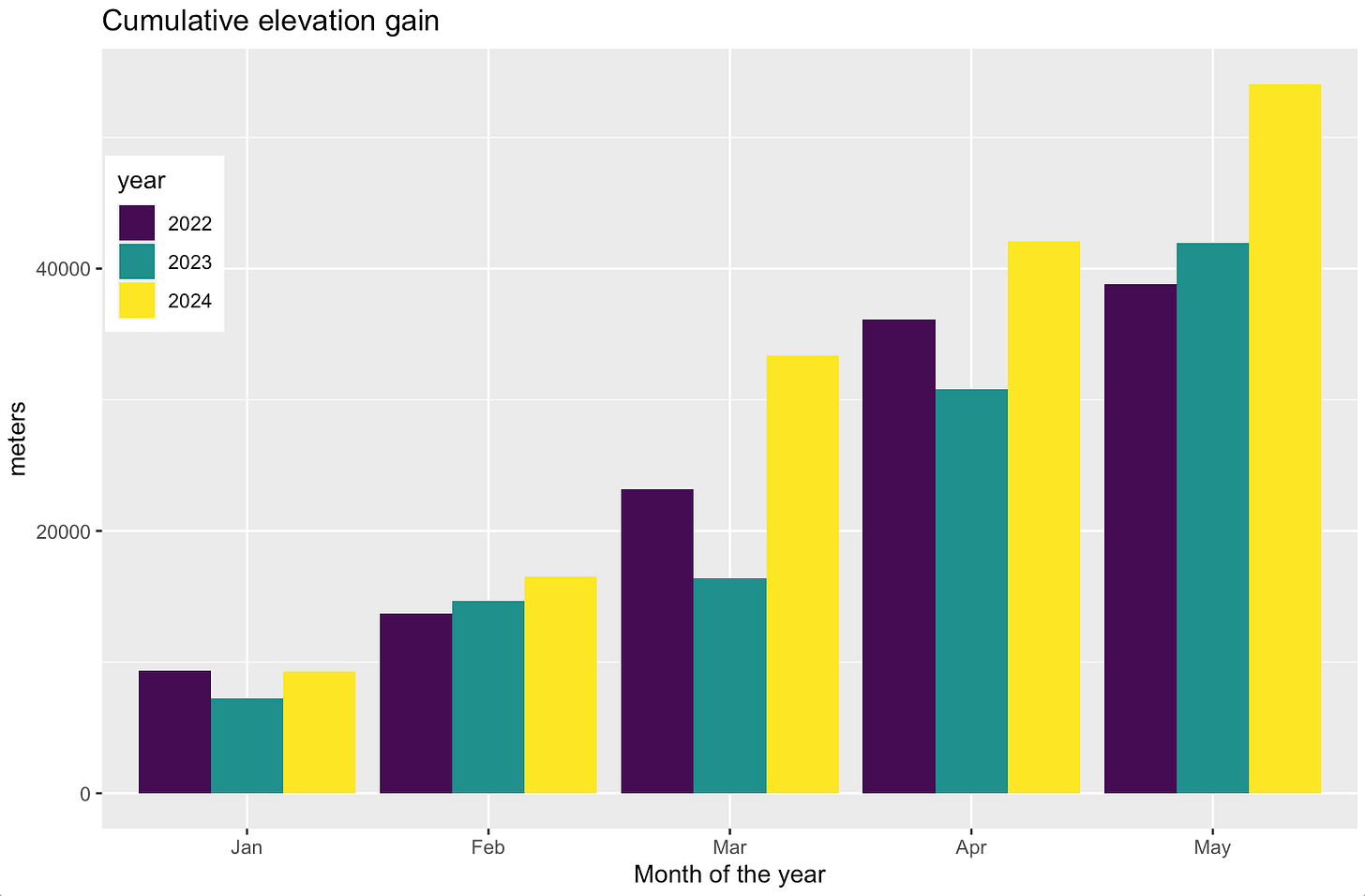

Here is my running volume in the 6 months preceding the race, which is at the end of May, for the past 3 years, since I started preparing for it:

You can see in 2022 I was training higher volume than in 2023, where I was also acutely injured in March. In May 2023 I was much fitter than I was in May 2022 (training volume is obviously just one part of training, and can’t capture much of our performance), while this year, in 2024, I was able to run higher volume but also to maintain fitness (and train hard, not only long).

We can see another side of training, by looking at the number of workouts (i.e. sessions that include some intensity). Not all workouts are the same, but here again we can see how in the past 2 years I could do more structured training, which was a goal I had set for my training:

Something I have noticed this year when doing long workouts with hard sections (e.g. this ~60 km run with hard climbs) is that I was not as limited as I was in the previous years in terms of peripheral fatigue, e.g. muscular problems, but it was becoming harder centrally, e.g. even just mentally, as my body seemed to be able to keep up better. Probably many people that don’t suffer from the same issues I suffer from (e.g. poor economy / durability, frequent muscular cramps, and in general a lower than average performance as the distance increases) might have a harder time relating here, but it was an unexpected learning and something that impacted a bit my training and the way I decided to race.

In terms of totals, I’ve averaged a bit less than 600 kilometers per month, with 11 500 meters of elevation gain, between January and May (lowest: 440 km, +7000m in February, when I raced the Barcelona half and then needed some time to recover, highest: 700 km, +17 000 in March).

Specificity: hills and heat

One of the aspects that I find most interesting is the specificity of training, and how we can manipulate training as we get close to the race, to help us become better at the target event. This could mean marathon pace before a marathon, or hills and passive heat acclimation before a long ultra which includes plenty of running uphill and downhill on a warm / hot day, as Passatore is. Specificity often means becoming more efficient, which is something at times we can quantify by looking at how e.g. our heart rate changes at race pace, or on the hills or in warmer weather.

There are some trade-offs here, between ‘getting as fit as possible’ and training for the specifics of the event, when the event is very long (i.e. pace is slow). In 2023, as I was focusing more on fitness, I raced an April marathon (1 month before the 100 km), while this year I preferred to only race a half marathon in February and then run 2 marathons (and a 50 km) at an easier pace (around zone 2, with a harder finish) and do a longer block of specific work, with plenty of hills and workouts on hills (e.g. pushing a long climb).

As a result, this year I ended up climbing quite a bit more:

and also running more long runs:

We can appreciate how in 2022 I was really making an effort to run long consistently, but probably overdoing it, which led to being in poor shape in May. On the other hand, in 2023, the year of fitness, I was doing fewer long runs, and most of them while getting closer to the 100 km (as things got more specific). I think this was the right approach, and this year it was similar, with most long runs in the last months.

This year I was able to do more, but I didn’t force any of this. The body slowly adapts. I don’t plan my training in detail, I just have in mind the main workouts I want to do over the next weeks, and then I go out and do ‘as much as I can do while staying healthy’, in between workouts. If I’m very tired I might hike, then run a descent, then see how it feels. Often it gets better after an hour or two.

Two years ago, when I moved to the hills for the few months before Passatore 2022, I developed plenty of issues, with Achilles pain, knee pain, etc. Last year, again, I had knee pain following the first weeks of hills, but then it got better. This year, I had no pain or issues. I believe this is simply gradual exposure, and years after years of this stimulus, that right now has become normal (as I have eventually moved to the hills!).

Hills: workouts

Something I’ve seen consistently over the years is that intensity makes me a better runner. However, intensity also breaks me routinely. This year, I tried something different, to accumulate more time at higher intensity, while minimizing injury risk. On top of cycling, I have also added moderate or hard hills. I have moved to Brisighella for a few reasons, one is certainly the hills around me, a perfect training environment for Passatore.

Pushing uphill gives me a great cardiorespiratory stimulus and none of the muscle soreness. I have done this quite a few times, during long runs (e.g. 45 km with 4 big climbs @ 6-8% grade at moderate intensity) or shorter ones (e.g. 8-10 minutes all out @ 8-9% grade). To be clear, I am one of those people that can barely do a hard session every week. I am always sore. I break down easily. I am weak from a muscular point of view. However, changing the training modality (bike vs run) and using hills allows me to run harder more frequently, and eventually stay fitter. No need to overdo it, but it is easier this way to make sure I am consistent with quality, not only quantity, of training.

Hills: specificity

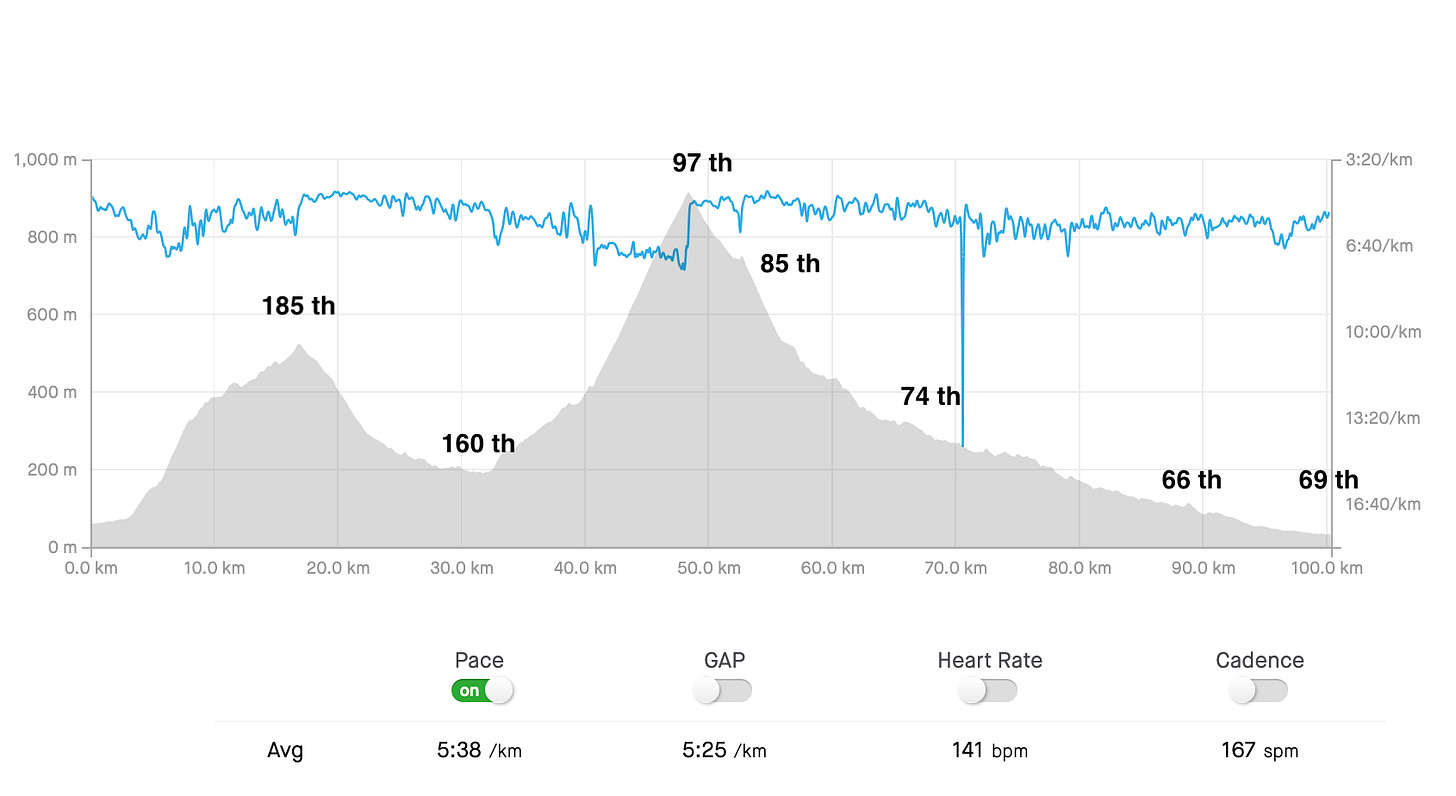

Passatore is 95% hilly and 5% flat. The climbs and descents are really long: we go up 17 km, then down 15 km, then up 16 km, then down 20 km, and then there’s a bit of a slight downhill with some rolling hills. The first two climbs and steep descents mean that you are running quite differently from the way you’d run on the flats, and for hours each time. As such, I think it is key to train this type of running, and become better and more efficient from a muscular point of view.

During the past 6 months before the race, I averaged between 3000 and 5000 meters of elevation gain per week (unless I was traveling, which I do try to keep to an absolute minimum these days), which I think has been essential for my race.

I lived for years in Amsterdam and struggled a lot the few times I’d go to the mountains or hills. Hills were a weakness. In the past 3 years I did my best to spend time in hilly places, and eventually even moved to one, with the result that it became a strength. I raced both the 50 km di Romagna and 100 km del Passatore passing many people on the climbs, only thanks to having spent so much time practicing this, over the last few years. I don’t think there’s any special workout that is particularly important here, but repeated exposure to this stimulus over a long period of time makes a huge difference in a hilly race: we become more efficient and its easier to run uphill.

In the race, I passed 63 people on the climb between Borgo San Lorenzo and Passo della Colla, which is a steep 16 km. It was probably the best part of my race:

Even when my heart rate was particularly high in the flat parts, I could see that while hitting a climb and maintaining the same internal load (i.e. heart rate) I would start passing people or I would work a lot less hard than them (based on breathing). It seems I became better at running uphill than at running flat. Here is the evolution of my yearly elevation gain in the past few years (again, not planned, just what my body allowed me to do, while building towards this race):

Hills hills hills.

Passive heat acclimation

Passatore is the last weekend of May, and starts in Florence, where you can barely breathe that time of the year. It is key to get to race day ready for a hot day. Two years ago I opted for training in the heat (i.e. active strategy). Training in the heat meant that I had to limit a lot what I could do and that I eventually trained poorly over the last 2-3 weeks before the race when the weather got warmer. Additionally, as the race is during a period in which days are getting warmer and warmer, training in the heat means you are always trying to catch up with changes in temperature, which is not ideal. This year, it didn’t get hot until the race, hence this strategy was just a no-go.

Last year, I opted for a passive strategy instead: the hot tub. The science on the topic is quite fascinating (check out Jason Koop’s book and podcast for a lot of great resources about the topic). Long story short, sauna or hot baths can give you a similar benefit to what you get from training in the heat, without messing with your training as much. Last year I found myself able to run at a low heart rate on warm days, which was certainly unlike me. This year, I also used the same strategy in preparation for the Barcelona half marathon, which wasn’t hot, with the idea that passive heat acclimation can improve performance even in temperate conditions (just like altitude).

For Passatore, I used the sauna for practical reasons, with a similar protocol: I spent about 25 minutes in the sauna, which was set to 70-80C, five times per week. I did 4 weeks straight, but with 5 sessions in the first two weeks, then 4 sessions in the third and fourth week. I also went twice on race week (Monday and Tuesday, racing on Saturday).

In the data above we can see a large drop in heart rate during the sauna after the first week or so, as expected. I’m finding it very interesting to see these changes and how we can manipulate different variables in the training process. During training, in the few warmer days we had, I also felt quite comfortable, for my standards.

The Long Runs

How long should the long runs be?

There’s no perfect answer to this question, and a lot depends on where you are at with your training / running journey, and what’s the goal of the long run.

Very long runs (e.g. 70+ kilometers) are risky (e.g. for injuries), and provide little to no added benefit after we go beyond certain durations / distances, from a physiological point of view (e.g. I can get a good training stimulus by doing 40-50 km with some intensity, and some people might even be able to push that a bit more or longer, but that’s pretty much it, it seems).

There are other reasons though to do very long runs, or what I call race simulations, i.e. going out at race pace (slow but not too slow) and practicing everything exactly like you’d do it during the race. This can be particularly useful mentally, and to practice managing intensity, fueling, test shoes / gear, or other important details.

Last year I learned a lot while doing race simulations and making mistakes, which eventually allowed me to race well when the race came. As we do more races and simulations, there is probably less need for these runs. This year I ran only one very long run (74 kilometers with elevation gain similar to the race), and this was enough to give me the confidence I needed, as I thought everything else was already sorted (intensity, fueling, clothing, gear).

In the last two months before the race, I preferred to go for runs that were a bit shorter (e.g. between 40 and 60 kilometers) and included intensity, for example pushing long climbs a bit harder, so that I could get a good training stimulus, without overdoing it with the distance.

Was this the right choice?

I think that from a physical fitness point of view, it was. However, mentally, staying out 70+ kilometers is really hard for me, and I am unsure if it is something I should practice more (I dread the thought). The mental drain I think is the main reason why I can only think of preparing for a 100 km once per year tops (as mental drain I also include having to deal with massive physical pain during the race).

A note on weight

Last year I was more concerned with my weight. I made an effort to be lighter, and it went okay (I never had issues in training or life, because of poor energy levels or else).

However, since increasing training volume even more last summer, and also adding cycling more regularly to my routine, I found it extremely difficult to maintain the same weight. At the beginning I tried to fight it, and eventually had periods of poor form, no energy and difficulties with training and just to function. Eventually I stopped fighting it and just ate what I wanted / needed to eat. This happened between last December and last February.

Since last February, I have not been bothered in any way by my weight, which is now quite a bit higher than it was in the past 2 years (I was 73 kg the day of Passatore, while I have been down to 66 kg the year before). I let performance decide on this one. If I train well and perform well, that’s all I need to know.

Training Takeaways

After spending three years trying different things specifically for this race, I think this is what I’d like to keep doing in the future, as I prepare the next editions:

Train for fitness between June and December (i.e. far from the race). This could mean a good marathon at the end of the year, or a half marathon even. Maintain some long runs (I love to spend time outside, and as enjoyment is a big part of why I do this, for me long runs are part of training all year long, but they might be more relaxed when I’m not in the few months that precede the 100 km race - specificity doesn’t matter at that time).

Train for specificity between January and May (i.e. before the race). For Passatore, this means hills, race pace, and workouts that tend to be longer (e.g. long hard climbs, tempo / threshold runs). Training in warm weather would be ideal but it is not practical.

Use hills for intensity and specificity. A way to train at high intensity while limiting injury risk and also improving efficiency at running uphills (a big part of the race).

Use passive heat acclimation to prepare for a hot race, and possibly other gains (e.g. increased hemoglobin mass). I like the idea of trying to keep some of this stimulus also all year round, and possibly get some sort of chronic adaptation (?) / struggle less in warmer weather.

Keep long runs moderately long, and add intensity (e.g. hard climbs). Limit extremely long runs at race pace to a minimum (e.g. maybe one, many weeks before the race). Spending all day on trails is no problem, I get no mental drain from that, quite the contrary!

See also:

The Race

I think that the training tends to be more interesting than the race itself (or at least, I’d love to read more training reports than race reports), so I will keep this section shorter, and try to cover a few points that I think can be useful to others or a future self, in terms of pacing and fueling in particular.

I went into the race aiming for a 8h 55’ - 9h 25’ finish (A goal), with a sub 10 hour (or top 250 finishers, meaning ~10h 30’ this year) as a B goal, and just to finish as a C goal.

I had written this for friends on the course:

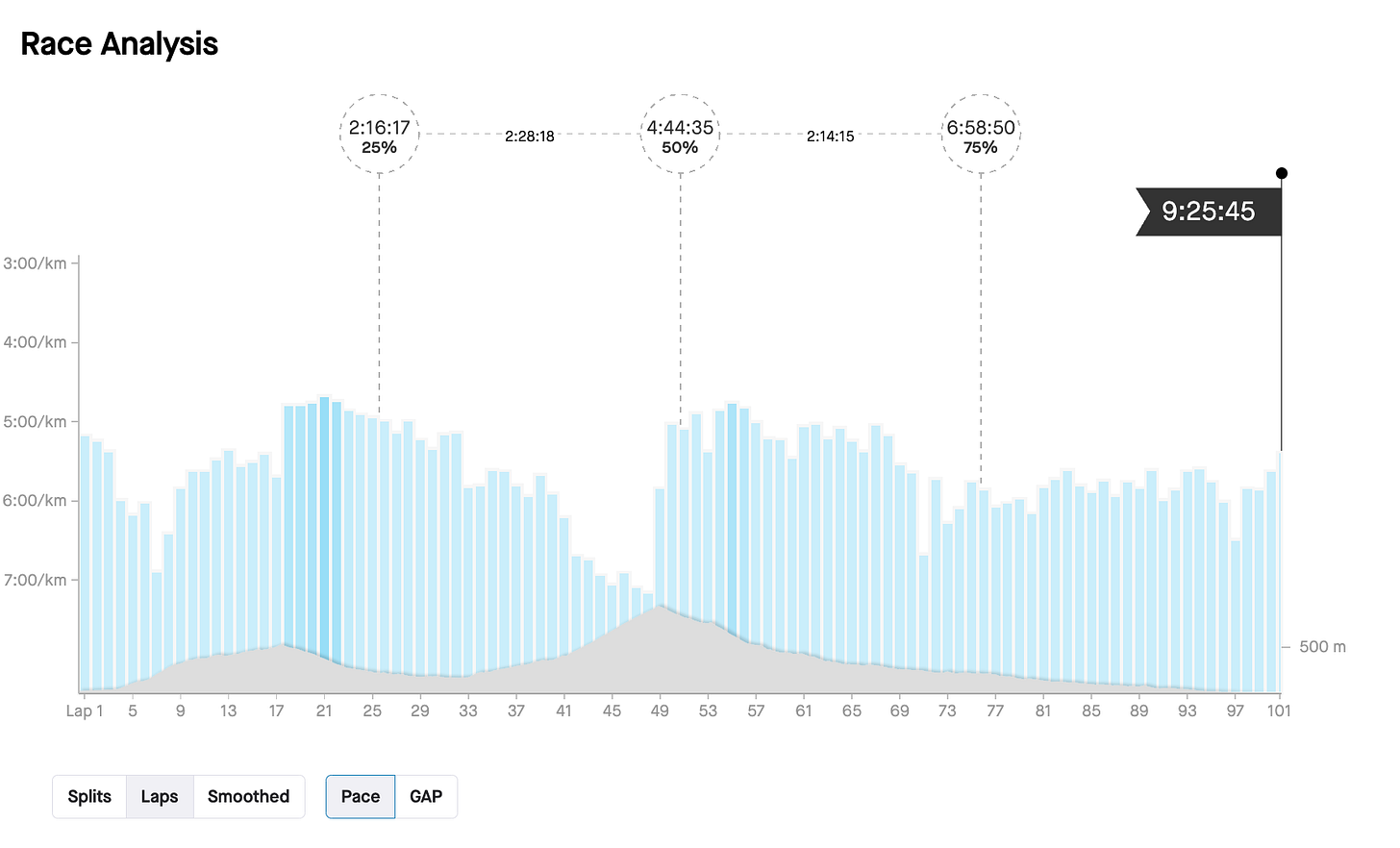

Eventually, I passed in Marradi in 6 hours, and faded a bit in the last third of the race, to finish in 9h 25’. I am extremely happy with the result.

Pacing plan

I find heart rate useful for these long events as it can be tricky at low intensities not to overdo it, hence I had planned to run at 135-140 beats per minute on average, based on trial and error during long runs and experience from last year's 100 km in Biel. This is 72-76% of my maximal heart rate.

Passatore is hilly so the strategy changes based on the grade, and I thought to allow heart rate to go up to 145-148 bpm or even a few extra beats when uphill (here we are getting up to 80-82% of my maximal heart rate), especially at the start when it is warmer (3 pm), then keep it < 140 bpm on the near-flat sections, and just try to save my legs on the downhills, trying to make up some time while running easy.

I planned to run the whole time, including Passo della Colla. Managing intensity with heart rate makes sense until about 60-65 km, at that point, I just use perceived effort and hang in there while heart rate drifts (in reality, we often have too many issues at this point in the race to worry about heart rate, which tends to be rather low due to reduced external load / pace).

Pacing execution

I felt quite tense and nervous in the 7-10 days before the race. I didn’t expect it, honestly. However, I was not relaxed and I was feeling the race. At the start line in Boston, where I couldn’t care less about my performance, I had a heart rate of 60 beats per minute. At Passatore, I was at 90 beats per minute. As I started running, (rather slowly) I was already at 150 beats per minute, above the limit I had set for the climbs. I then just tried to stay calm, slow down a bit, and focus on my breathing, to make sure it was the way it should be / feel for this type of long, low-intensity effort. While the start was warmer than expected (it was supposed to rain, but eventually, it didn’t), things got better as we got up to Fiesole, with a bit of breeze and clouds covering the sun, after the first steep climb.

At this point, I felt like it was a good day to race, as it wasn’t as hot as it could have been, and I decided to go for it and see if I could hit 9 hours or get close. I ran an easy downhill (17 km - 32 km) but at a decent pace, and then a steady climb up to Passo della Colla (48 km), which was probably the best part of my race, passing plenty of runners. At that point the temperature was really good for running as we were above 900 meters of elevation, and even in the descent (which was quick but controlled, not to damage the legs too much), my heart rate went down the way it was supposed to (which is not always the case when tired or when it is too warm):

After a long descent, quite controlled, in which I was feeling pretty good, I passed Marradi (“where the race starts”) at about 65 km, and I had a side stitch. I didn’t have one of these in ages, but it kind of killed my race. I slowed down, and tried to breathe differently, but it wouldn’t go away. It stayed with me for more than an hour, during which I also didn’t eat or drink, as I was afraid I’d make things worse and would need to stop. It was quite a hit also mentally, but I just tried to keep moving the way I could, waiting for it to pass.

At about 80 km (after an hour and a half), it resolved and I felt normal, but tired. I started eating again in small bits, and drinking more, but at that point mentally I was really drained. Maybe a mix of the distance and dealing with the pain for so long.

In the pace plot we can mostly see changes due to the hills:

while in the grade-adjusted pace plot it is quite clear that I struggled a lot in the last third of the race (I stopped to pee only once, at km ~71, which is the pace drop you see below):

So, how did it go?

I think I paced myself well and was a bit unfortunate with the side stitch. Not sure if I drank or ate something too quickly or else. My heart rate was definitely above where it should have been for the first part of the race, but I went more relaxed on the downhills and got things back on track soon enough, I believe.

The last 30 km felt strange, I was in physical pain but it wasn’t my legs or cramps (the type of pain I’m used to), it was the side stitch first and other stomach problems later, hence I was going slow because I couldn’t do otherwise, but I was also feeling like I was saving my legs more than I would have done in normal conditions. Mentally it was harder than expected. The support on the course was really good though, and knowing that I’d meet family and friends in different towns helped me to break it down to small steps. 15 km to Brisighella. 14 km to Brisighella. 13 km to Brisighella. You know what I mean. Lots of cyclists supporting runners, families and kids out until very late, it was really nice to pass through small towns between Tuscany and Romagna and see how much the race is felt down here.

Only at about 95 km I felt my legs turning into stones, and really struggled with physical pain in my lower body, which I didn’t have for the previous 9 hours. This tells me the pacing was pretty good and maybe I do have some margin in terms of spending time “between thresholds” and not only below the first one, as I get better at the distance and more ‘durable’. This last point is the most exciting one for me in terms of training now, i.e. trying to ‘race’ these long distances, as opposed to just running them.

I am quite happy also that when struggling the most, pace remained decent, and I faded much less than I did last year at the Biel 100 km, which has a easier course. I lost a few positions in the last kilometers, but given my obvious limitations, I am really happy to close in the top 2%.

Pacing execution: 8/10.

Fueling plan

After plenty of trial and error, with nausea, muscle cramps, and other issues I experienced in the past few years, I settled on 1 gel every 6 km as my fueling strategy, with no other food. This would make for 16 gels over 100 km, plus 1 before the start. I am using gels with 25, 30 or 40 grams of carbs, alternating them for the first half of the race, while going with 30 grams for the second half of the race.

I have planned 3 gels with caffeine (one at approximately 25, 50, and 75 km).

Fueling execution

I had 13 (12 during + 1 before) gels for a total of 435 grams of carbs (I had planned 515 grams). Everything went according to plans until the side stitch at about 65 km. At that point, I opted for not eating, and later when the side stitch went away, I had a bit of nausea and struggled to eat, so I had just a bit of gel, then another bit, and lowered the frequency.

I am not sure what I would do differently here. I had most of the larger gels in the first part of the race and uphill, and I wonder if that was a problem and I should have eaten less, or if it was just bad luck. My reasoning was that on the downhill less food is better, as everything moves a lot more and I do not have the most reliable digestive system, so to speak.

I think it is hard to extrapolate from this little data (one race) in any meaningful way, hence I would do the same if I had to run tomorrow. However, I do have more doubts today than I had before the race. The rhetoric is to eat more, but I wonder if I should eat less (maybe just having regular gels with 20-25 grams of carbs and dropping the ones with 40 grams). Not being in pain or distress should be better than having more carbs (a minimum effective dose approach). I am still inclined to just use gels for a road race even this long, but it does get harder after ~7 hours in terms of nausea, something I never practice in training for obvious reasons.

Fueling execution: 6/10.

Hydration plan

I cannot bear to drink anything but water for a race this long (otherwise I get even more nausea), so I do not drink carbs nor do I drink electrolytes, but I take electrolyte pills from Precision Hydration (mostly sodium) and separate my food and my hydration). Hard to be sure about these things, but I think the pills have been helpful in the past years, given my high sweat rate and sodium loss.

For the race, I had planned 1 pill every 12 km. In terms of water, I had planned to go by thirst, and sip water when having gels (a must) or pills if possible. I can’t keep track of water in any meaningful way, hence I do it this way, which seems to work fine for me.

Hydration execution

All good here. I had a trusted friend on the bike helping me out with water, and it was really helpful. I drank plenty, but tried not to overdo it.

Hydration execution: 9/10.

Race Takeaways

This is my second 100 km race, and the first Passatore I finish. I think we were somewhat lucky with the weather, which was warm only for the first hour, and I am glad I tried to race and go for an ambitious time (9 hours) even if eventually I had some issues and didn’t have it in me to race that ‘fast’.

I found the mental aspect of the race to be harder than expected. I run a lot. I train hard, I train long. I am somewhat driven to overdo things, and as such, I thought my type of training, prepares me well mentally for this race. However, the level of physical pain I had to deal with during the race, is something I had probably experienced only very few times. It was really hard and maybe I had forgotten how hard it could be. Something to remember for next year.

Apart from the mental aspect, the key in these races is to adapt. Some things go as planned, others don’t. It’s warmer or colder than planned, it’s harder or easier to eat than planned. There’s always something when you are out for 3 times the duration of a marathon. While it is key to have a plan, I think it is equally important to be able to adjust as you go: let your heart rate go a bit higher than planned on a climb without stressing, but then make an extra effort to recover on the descent (i.e. don’t ignore that your body is working harder, but find ways to compensate). Skip two gels but then make an extra effort to get back into eating regularly, even if in smaller portions. Stay on top of your hydration all the time, etc. - adjusting on the go is key to a successful ultramarathon.

That’s a wrap for the 100 km del Passatore 2024.

9 hours and 25 minutes.

67th of 3500 runners.

Nerves, heat, pain, self-doubt, darkness, grit, beauty, family, friends, joy.

One year to the next Passatore.

See you out there!

Ways to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

If you already use the HRV4Training app, the best way to support my work is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you!

Coaching

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and fill in the athlete intake form, here.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Congrats! I know you mentioned cramping problems before. I just listened to some interview with David Roche (winner of Leadville 100) and he mentioned that sodium bicarbonate helped him with cramping. It's nothing something I heard before, but maybe it's worthwhile looking into.

Well done for your performance and for sharing your preparation and passion for sports science with us. Your article is very interesting.