How to turn the worst running economy ever measured into sub-3-hour marathon performance in only 14 years

a true story

This blog started as a bit of a joke, but hopefully, there’s something useful in here for other endurance athletes.

Let’s start with a bit of background.

When I was in high school, our physical education teacher would corner me and ask how much I'd been smoking, given my complete lack of endurance.

I never smoked, but that’s how good I was as a runner, despite being active and doing sports since a very early age.

Many years later I fell in love with running. I left my country in 2009 when I was 25 and started pouring myself into work, finding in running a much-needed break for my mental health, more than anything else. It wasn’t love at first sight, but I slowly started to enjoy it more and more.

After making some initial progress, I settled into middle-of-the-pack performance for the half-marathon distance (1h 45’ or so). As my work brought me closer and closer to the science of exercise and performance, I started to learn more about training and made some adjustments that led to large performance improvements (1h 24’ half marathon). At a certain point, back in 2017, I thought I could even run a sub-3 hour marathon, a decent target for a recreational runner. This is when I had to face an unfortunate truth: I was a (negative) outlier in terms of running economy, or energy expenditure in general (even at rest). As a result, my performance would drop dramatically between the half and the marathon distance, beyond what you can expect from most runners of similar abilities.

I tried, and I tried again. No matter how much I would run in a week or how many long runs I would do, I just couldn’t keep up the pace, depleting very quickly, and experiencing all sorts of muscular problems and cramps. At a certain point, I started to break and called it a day. Running a sub-3-hour marathon wasn’t for me, and being injured all the time wasn’t worth it. No drama of course. I still loved running very much regardless of performance, to the point that these past few years, I was running more and more, regardless of my declining performance.

The interesting thing about running economy is that the more you run the better it gets, but very slowly, over many years.

Eventually, following a “reset” which I described elsewhere, I started improving again over shorter distances. At this point, I knew better than to fool myself, and I was still quite convinced that I just couldn’t run a sub-3 marathon (despite running a half in 1h 21’ 45”). - just ask Dave.

Long runs at race intensity don’t lie and they were just too slow and often led to cramps.

Until they didn’t. Focusing on a few key aspects over many months (I will discuss them below), and training at the right intensity (hint: internal load), I was finally able to improve my running economy and overall fitness to aim for a sub-3. I would still be “underperforming” given my times over 10km and half marathons, but it would be just enough to get it done, possibly.

Eventually, I ran 3 hours and 2 minutes in Ravenna in November, cramping terribly only in the last few kilometers, and then after a few months of great training, followed by a few injuries and setbacks, I gave it another shot in Manchester where I ran 2 hours and 59 minutes (still cramping for about an hour, but managing to reduce pace just enough to make it - an exhausting exercise, mentally).

Considering how it all started, it is quite amazing to me how the body can adapt to proper training, following the science, and experimenting a bit based on your own physiology, limiters, and strengths.

In this blog, I tried to highlight some of the main pillars as well as some of what we could call more advanced aspects that are relevant to marathon training, and that helped me to get there.

What follows should be obvious to most people that understand endurance training, but might help you if you are a beginner or have similar issues.

The Pillars

These are the non-negotiable, at least in my experience:

Prioritize your health and training

Slow down, then train more

Train hard

Train at your current fitness level

Prioritize your health and training

There is no training without health.

Do what you can to eat well, sleep well and enough, move, spend time with loved ones, and address the elephant in the room: whatever it is that is stressing you out.

If you want to get better at training, prioritize your health and training will become easier. This often means reducing other stressors. You need to put yourself in a position to assimilate and respond positively to training stress, and that is unlikely to happen if you are chronically stressed for other reasons.

For me, work has always been the priority and the main stressor for many years. I would often see drops in HRV because of work stress more than training stress, clearly highlighting what was causing issues in my life. This is not something that you can change overnight (but nothing around endurance performance is!), but it needs to be addressed.

As I approach my 40s, I made choices that reflect my beliefs and what I try to preach.

Once I can eat, the choice is very easy:

Time before money. Mental and physical health before money.

Let go of external pressure, it is not worth it.

Follow your path.

Okay, enough with the preaching and back to training. The way this translates into daily life is that health and training are prioritized. There’s always a lot of extra to do for each one of us. It makes little sense to postpone training because I have to do another endless task. Training is time-constrained. Once you have done it, there are typically another 20–23 hours in the day.

Prioritizing health and training was the first step in improving my performance.

Slow down, then train more

This one gets people all worked up, but it’s really simple.

I used to do all the things you’d expect a runner to do: the hard intervals, the tempo runs, the progressions, and the longer runs. I wasn’t making any progress. I wasn’t able to run more or to run longer.

How did all of this change?

By slowing down.

Between 2009 and 2010 I made the usual progress that all novice athletes make. I ran my first half marathon in 2 hours and 8 minutes, and my second one in 1 hour and 42 minutes, 6 months later. Then, between 2010 and 2016 I trained and made zero progress. Six years without improving by a single minute.

The reason? I was always running too hard. I had no idea what it meant to run easy. It felt easy, it was slower than race pace, but it wasn’t easy enough. Perceived effort is my favorite tool today, but it is of no use to most beginners. Most of us do not have an innate ability to understand when we are working too hard, as beginners.

In 2016, thanks to Matt Fitzgerald’s popularization of Stephen Seiler’s work (and a heart rate monitor), I started running easy for real. The changes have been quick and dramatic. I could train more. I could do harder sessions better. I could run longer. 6 months later I ran 1h and 27 minutes in the half, and another 6 months later I ran 1h and 24’, or 3’ 59”/km, almost 20 minutes better than my previous PR, which I could not improve for 6 years.

Running slow allows you to run a lot, which brings many benefits, and gives you the ability to perform better in your hard sessions too.

See also:

training intensity distribution (make sure to read this one before you get all worked up about “polarized training”, context matters!).

Train hard

Training easy should be prioritized, as it will build the foundations required to assimilate the hard stimulus. However, training hard should also be a key part of the picture.

The two go together, and in my experience, it was very easy to see: I made zero progress in performance by training hard but not easy, and therefore at low total volume (this is how I trained between 2010 and 2016).

I also made zero progress in performance when training a lot and always easy, so when maximizing volume at the expense of intensity (this is how I trained after my worst injuries, between 2018 and 2022).

Then, I made a lot of progress when combining reasonably high volume (for me, 90-130 km/week, typically over 6 days), with high intensity (let’s say 3 sessions over a 2 weeks cycle, as I cannot handle 2 sessions per week without breaking down). This is how I trained between 2016 and 2018, when I made the first jump in performance, before breaking, and how I trained again between 2022 and 2023, when I further improved my performance, with some adjustments.

Again, this is my experience, not a universal truth, but hard training is how we get better, once we have reached a high volume of easy running. For the first few years, it is as simple as training many hours, and going hard once in a while. Mixing easy and hard will break the monotony of always doing the same thing, and likely bring additional benefits. Give it 6 months with high consistency and compliance, and you will start seeing improvements (your effort will be lower at a given pace or your pace faster at the same effort).

Once we have developed some fitness and a better aerobic base, training intensity distribution becomes more nuanced, with time spent in different zones increasing or decreasing depending on the time of the year (e.g. how far from the goal event), current limiters, and the demands of the goal event (principle of specificity, discussed below) - more on this, later.

see also:

Train at your current fitness level

Endurance training takes time.

While you might be able to make some quick gains in VO2max, it is unlikely that you will develop the capacity to work at a large percentage of that max for long, in a short time. When it comes to running economy, my main limiter, changes in muscle fiber type will take many years.

It took me a while to understand that I couldn't force these changes and that I was probably training in a counterproductive way by doing long runs at goal race pace (i.e. guided by external load) instead of race intensity (i.e. guided by internal load, based on my current abilities).

When I started not bothering about the depressing pace of my long runs but worked on maintaining my heart rate in the right place for a marathon effort, and doing this repeatedly as I finally wasn’t compromising my health or recovery anymore, I made progress.

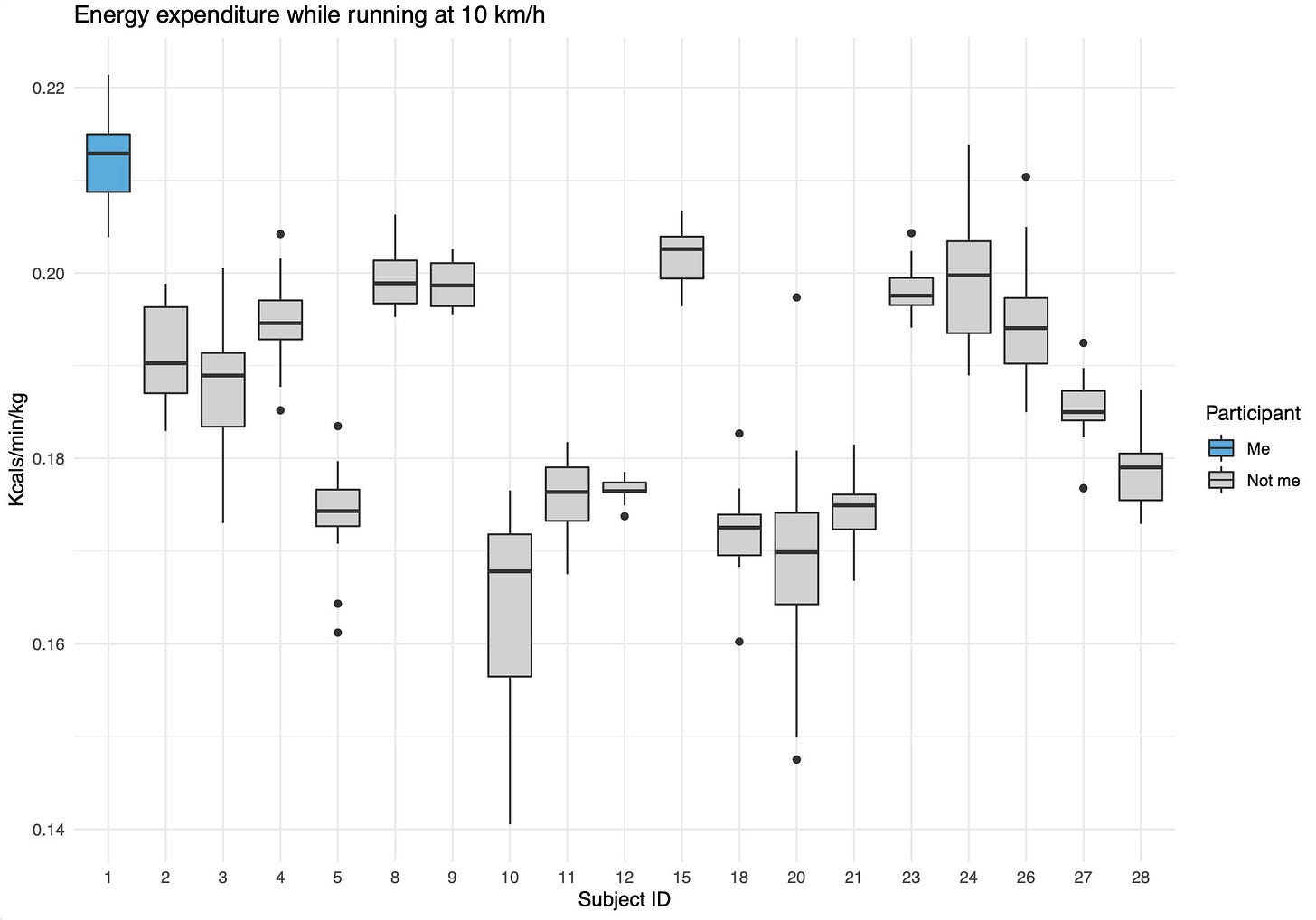

Below is the energy cost of running at different speeds for me, measured via indirect calorimetry 10 years apart (gray and yellow boxplots) and then again this year (blue boxplot). The lower the cost, the better. You can see quite a dramatic change over a decade, but still quite a large change even in the last year, as I am now running more than ever (570 hours of running in the 12 months between the two tests).

We all set ambitious goals for ourselves, but these goals can quickly derail our progress and performance for many years, if our bodies cannot keep up with them, as it was the case for me.

Keep training, and train hard, but also train smart, at your current level, not at the level you’d like to be. Give yourself time.

See also:

The Advanced Stuff

Once the aspects above were covered, I was still not enough for me to run a decent marathon.

The reason, was my limiter (poor economy), and here are some more advanced aspects that made a difference for me, when implemented:

Specificity

Managing intensity just right

Fueling

Specificity

I haven’t used the magic word (“polarized”) much in the text above, to avoid being misunderstood, but here we need to get a bit more specific on terminology and actual sessions. It’s the advanced section after all.

Broadly speaking, we can break down training intensity distribution into 3 zones.

We have an easy zone, a moderate zone, and a hard zone. The easy zone is below our aerobic threshold (first lactate or ventilatory threshold): think very easy, conversational pace. The second zone is below our critical power or speed (near the second lactate or ventilatory threshold): think some difficulty in saying a full sentence. The third zone is… well, hard.

Polarized training in the traditional sense means that more emphasis is given to the easy and hard zones, and less on the moderate one. An alternative would be pyramidal training, in which more emphasis is given to easy and moderate zones, and less on the hard ones. For most beginners, polarizing training means breaking an unproductive pattern: running always too hard, always doing the same type of training. Nobody is arguing for Kipchoge to stop doing his 40 km long runs near marathon pace. We are arguing for beginner athletes to better structure their training, and learn what it means to run easy. When we look at the problem from this angle, it is a good idea to polarize more your training regardless of volume (total amount of hours in a week). This is just a first step towards learning to run easy and breaking training monotony (more about this, here).

Now, fast forward a few years, and you have developed an aerobic base, and are able to train at different intensities, not just easy or hard. Your physiology can now stabilize for long in “middle zones”, and these zones are key to marathon performance. Here is where the principle of specificity plays a role. Specificity means that you will train close to the demands of your event. This is why in the past two marathon training cycles I have split my training into two blocks:

first, a VO2max block where there is more low-intensity training, and the high-intensity training is harder. The goal here is to get faster. We are lacking specificity as we are far from the target event. This is “polarized” training.

secondly, a lactate threshold and steady-state block where we have a similar amount of low-intensity training, but the hard training is mostly at moderate intensity. The goal here is to extend the amount of time I can run faster and also get more efficient at marathon pace. This is specificity. This is “pyramidal” training.

Training at marathon intensity (not to be confused with marathon pace) was probably one of the key changes that allowed me to finally run the sub-3 marathon. But how do we find marathon intensity?

Read on.

Managing intensity just right

Specificity is key and we need to run at marathon intensity to get better at it, but what is marathon intensity if we are particularly inefficient and cannot rely on pace, due to a mismatch between predicted times and what our physiology can do?

Trial and error is how we sort this out.

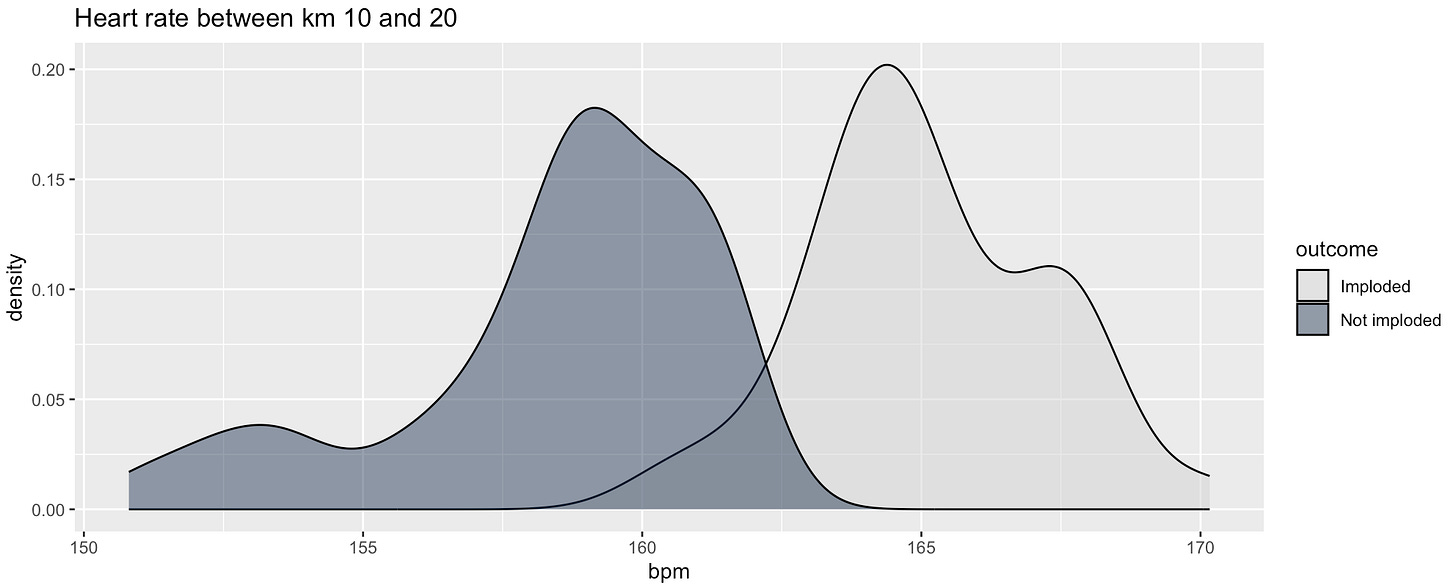

In particular, I started looking at my heart rate data to determine what could be a sustainable intensity, separating successful long runs and marathons, and not-so-successful ones (the “imploded” category below includes races where I cramped really badly already before 30 km, resulting in quite a miserable day).

Looking at the data above with respect to the “outcome” shows a clear picture, internal load (heart rate) doesn’t lie and clearly separates outcomes. This means that a slightly higher heart rate always resulted in poor outcomes, and therefore, heart rate becomes a key parameter to manage for me. It’s just a few beats, but they make a great deal of difference.

From the graph above, we can derive that aiming for 85% of my maximal heart rate or ~159 bpm for the first half of the race seems a safe strategy. For the marathon in Ravenna, I was a bit above that, and I did cramp badly and had to run a slower last few kilometers. In Manchester, heart rate was exactly where it was supposed to be, and despite experiencing my usual muscular issues, I could manage them and I did not have any large reductions in pace.

Heart rate here matters more than any other signal because this is the hardest my body can work for this distance (in different environments and for different fitness levels, with some caveats). External load (speed or ‘power’) cannot capture any of this.

If you do not have the same limiters, marathon predictors might work well for you. For me however, they are all overly optimistic as they do not factor in that issues in running economy, cramping, etc. - do not impact my times up to the half marathon This is not something I could just figure out using a formula or models based on other people, as my own physiology and limiters impacted what I could do and what intensity I could sustain. However, paying attention to the data, and then doing all my specific training at this intensity, regardless of pace, allowed me to successfully train for the distance, and eventually reach my goal.

Note that this does not mean that I need to use heart rate for every marathon now. Having trained more and more at this intensity (principle of specificity) I am now able to use perceived effort too (in fact, my chest strap stopped working after a few kilometers in Manchester, providing me with the perfect occasion to test my new skill).

However, the data was instrumental in getting there. We can use tools without becoming one.

Fueling

Preparing for an ultramarathon is probably what made me finally understand that certain distances are different from others, and require a more methodical fueling strategy.

It took me a while to find the right setup, what to eat, how frequently, etc. - I think this just comes down to experimenting a lot, and maybe I didn’t experiment enough before. In the past year, with more experimenting, I became quite confident with different strategies for different races and distances, even though my intake is still on the low side at times.

For a marathon, I currently eat 1 gel (25 or 30 grams of carbs) right before the race and then 1 gel every 7 km (which is a bit less than 30 minutes at 3-hour marathon pace). I also take electrolyte pills (these ones from precision hydration) with the same frequency. I then drink at thirst based on what’s available on the course. More frequent intake gives me GI distress, but this might change in the future with more GI training. Since I’ve started to be more methodical, I have experienced fewer lows. This is a key aspect of marathon training which might not be so obvious to beginners, especially in terms of how much to eat and how frequently.

Fueling and weight, together with the energy cost of running, come together when trying to figure out how much I need to eat for a given distance. For example, assuming a pace of 4’10”/km, I am at 78% of my VO2max. My consumption at that intensity is ~940 kcal/hour, hence I need 2820 kcals to get to the end in less than 3 hours, and I have ~2000 in storage assuming full glycogen stores. An extra 1000 kcals means 300+ grams of carbs over 3 hours or 100 grams / hour (I am intaking quite a bit less).

The math here is obviously flawed and oversimplified, but you get the point: weight, running economy, and fueling all matter, and I have tried to work on them by 1) running a lot, running hard and running at marathon intensity, which improve economy 2) fueling more and better (special thanks to Andy, Sean and Precision Hydration for their guidance) 3) managing my weight better, but without stressing too much about it.

Keep in mind that nutrition outside of training will drive the vast majority of your metabolic flexibility, something I learned only years later, but that eventually made it much easier to run long even at sustained intensity (e.g. marathon pace). In particular, my fat oxidation at marathon pace after heavily periodizing my diet became so high that I would now need 0 (yes, zero) grams of carbs per hour to run sub-3.

That’s a story I documented here.

see also:

What about heart rate variability?

Heart rate variability (HRV), similarly to exercise heart rate, is a powerful tool, as long as we don’t become the tool.

In my experience, as my understanding of HRV has evolved in the past decade, this tool was instrumental in many of the steps above. However, this does not mean “following the advice of an HRV app or wearable”, but it means understanding what HRV is, what is a positive or negative response to training, how it can track different stressors, and then use this information for behavioral change (in life and training).

For example, HRV helped me understand where the negative stress in my life was coming from (being overworked), and as such, it helped prioritizing health and training.

It also helped me understand what it means to train at the right intensity, an intensity that allows your body to quickly re-normalize. Remember that stability in HRV highlights a positive response, and a prolonged suppression does not mean that you worked hard, it means that your body can’t deal with the stimulus you have provided and you have likely overdone it.

Resting physiology tracks also quite well with changes in body weight, and in fitness, therefore providing additional feedback on how these changes have impacted me.

If you are interested in using HRV, here are some useful pointers:

That’s a wrap

Prioritize health and training. Slow down, and train more. Then train hard but at your current fitness level.

In my experience, given my limiters, specificity and finding the right intensity for marathon training, as well as fueling were important aspects I did not grasp at the beginning, but that I think helped me a lot in the past year or so.

Finally, using data (heart rate during exercise, morning HRV measurements), can help us in different ways, eventually allowing us to become better at using perceived effort or feel to guide decision-making, as well as providing valuable objective feedback in relation to training and other stressors we might be facing.

That’s more or less how I turned the worst running economy ever measured into sub-3-hour marathon performance, in only 14 years :)

I hope this was informative, and thank you for reading!

Ways to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

If you already use the HRV4Training app, the best way to support my work is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you!

Endurance Coaching

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and fill in the athlete intake form, here.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

One of the problems with slow running is maintaining proper stride rate.

I have hard time maintaining stride rate when I run fast, but when I run slow,

the stride rate becomes atrocious.

I know you are proponent of polarized training (and so am (or was) I), but there's other ways.

What do you think of "Easy Interval Method" (essentially a variation on Igloi)?

Very interesting and inspiring, especially the example from HRV4training relating to training intensity distribution in different phases. I'm new to polarized training and would like to find out more about how to best to use it and pyramidal training in the different training phases. Do you have a paper on that or could you point me in the right direction?. I'm self-coached, so any help would be much appreciated :)