[TrainingTalk] Notes on training zones and training intensity distribution

and a note on lactate

I have received a few questions about “zones” and how I set mine, hence this blog post.

At this point in my journey, I use training zones more in a descriptive than prescriptive way. However, there were phases in which it was certainly key to use them in a more prescriptive way. Over the years, I have mostly figured out my zones based on training and racing data (some initial fixed thresholds and lab testing too, but more trial and error and assessing performance or feel or my ability to perform a given session in which I maintained - or attempted to maintain - a certain intensity). This is especially true for zone 3 or what I consider marathon pace - more on this later.

This was a long process (many years), hence not a simple formula others can likely apply, but hopefully there is something useful below.

In this blog, I cover this process, trying to clarify some points of confusion (e.g. zone 2, training intensity distribution, differences between cycling and running, how things differ when we are beginners, and more).

I also provide an overview of my progress over the years, how training has changed, and what are the takeaways based on performance over different distances.

Overview

In this blog:

What is exercise intensity?

What are training zones?

Low-intensity zones

Beginners are different

Splitting Z1 and Z2 as we develop

Running vs Cycling, can you go too easy?

High-intensity zones

A brief history of the past 15 years of my training

Performance and limiters

When to use heart rate?

My Zones.

Is this the only way?

Let’s get to it then.

What is exercise intensity?

Training can be broken down into frequency of the sessions, duration of the sessions, and intensity of the sessions. Duration and frequency are easy to monitor. Exercise intensity is defined as energy expenditure per minute while performing a task, but this is not feasible to measure outside of laboratory settings.

Since heart rate and VO2 (energy expenditure) are linearly related, we can try to use heart rate to estimate energy expenditure, hence the use of heart rate monitors to determine exercise intensity.

Thus, with heart rate, we determine the intensity of exercise, which is a key factor in determining the potential effect of a session.

What are training zones?

With training zones, we establish ranges of exercise intensities that should result in certain physiological responses when we spend time exercising at those intensities. It is a way to break down continuous measures (like heart rate) into something possibly simpler to understand or use. This has some advantages, for example, given day-to-day variability and inter-individual variability in general, using zones, removes some of the problem / noise (we minimize the impact of day-to-day variability).

Here I am considering a 5-zone system, where Z3 is the only zone that is actually demarcated by what we consider somewhat measurable thresholds (the first and second lactate thresholds, LT1 and LT2 or the first and second ventilatory thresholds, VT1 and VT2). There are variants of this, but this is the system I am using here. Hence Z1 and Z2 are both low intensity for me, below LT1, while Z3-Z4 are all high intensity, above LT1.

Z3 is often called moderate, or the middle zone, but in my view, Z3 is also high intensity. Why? Because training above LT1 causes disruptions in autonomic activity similar to high(er) intensity training, hence when we are above LT1, we are stressing the body. Z3 is where we typically run a hard marathon, or a very long tempo run, and in my view, that type of training is hard training.

Other resources:

Low-intensity zones

Low-intensity zones are typically defined as the ones below LT1, the first lactate threshold. As beginners, we often don’t have access to this type of testing, or metabolic testing (using indirect calorimetry to measure gas exchange). A decent compromise, which is not perfect but can help from a practical point of view, is to use heart rate.

For example, many years ago when I started paying more attention to exercise intensity (something I discuss in more detail in this blog and also below), I simply used 75-78% of my maximal heart rate, to determine the limit between low-intensity and not-so-low-intensity exercise. If you go this way, it would be very useful to know your actual maximal heart rate, maybe from a short race or some hill repeats, as opposed to using formulas based on age, which tend to be quite inaccurate. Later in my journey, I also measured lactate, which was generally in agreement with heart rate (only recently, after a few years of high volume training - e.g. ~6000 km/year of running - I have seen a small change in the relationship between heart rate and LT1, as I am now able to sustain a higher heart rate at LT1, despite a lower maximal heart rate - I discuss this in a bit more detail towards the end of this article).

This is an intensity at which we can have full conversations and not feel out of breath.

As I was unfit at that time, any running would bring me near or above this threshold (the upper end of Z2). Let’s break down this point a bit more, as I think it is quite important.

Beginners are different

When you are a beginner, there is no Z1, and low-intensity running often requires walking breaks (see also this blog where I talk about training intensity distribution).

Aerobic capacity is poor, and as soon as we start running, we get really close to the first lactate threshold (or above it). As beginner runners, the focus on Zone 2 kind of makes sense, as long as we understand that it's about going easy, not about training harder than a certain intensity.

Other resources:

Splitting Z1 and Z2 as we develop

In practice, I run more in Z1 these days because as you get fitter, Z2 becomes very demanding (too tiring for my legs, I’m not fresh then for proper sessions despite lactate staying low, risk of injury is much higher as external load - pace - gets quicker and quicker for a low heart rate, etc. - here is where the trial and error comes in).

We also need to keep in mind that there is no measurable threshold between Z1 and Z2 (I consider LT1 the upper end of Z2), hence this is somewhat based on how it feels and what I can do when sore or tired due to high volume and intensity. For practical reasons, I now consider race intensity for a 100 km race my lower-end Z2 (hence a proper effort, not just a jog, which would be Z1), and race intensity for a 50 km race my upper-end Z2. Obviously, this makes sense only if you train for those distances. Otherwise, simply consider Z1 a type of training that does not leave you tired mentally or physically, and Z2 a more focused low-intensity effort, still below LT1.

In my case, I set the threshold between Z1 and Z2 at 135 bpm (my maximal heart rate is 185-187 bpm, while my training is mostly around 125 bpm these days. A proper Z2 run would be around 145 bpm, or even a little more). This means that 100 km intensity for me is the low end of Z2, with some margin. A better athlete will probably run towards the upper end of Z2 instead, around LT1. Granted that this is rather arbitrary, but the point is that most of my training is very far from LT1, for the reasons mentioned above (less risky, very similar benefit, the same is consideration do not apply to beginners, for whom a focus on Z2, simply means trying to go easy, the point is to stay below an upper end for a beginner, not above a lower end).

Running vs Cycling: can you go too easy?

I believe it is important also to realize that running and cycling are very different sports, and the focus on Z2 is typically in cycling, where you can certainly train too easily ("you are just sitting there"), while in running, it is hardly possible to train too easy (you'd be walking otherwise, there is no equivalent of walking for cycling).

Running is always hard on the body, hence we tend to shift more towards Z1 than Z2 as our volume increases and we become more fit. Being more or less prone to injury also plays a role (i.e. I have to be very careful).

A common question after reading this, is the following: should you do your easy training at even lower intensity? I think that it depends. If you are already running the available hours you have, have no interest in increasing volume, and your easy training does not compromise your hard sessions, then probably there is no need to change. If you want to step up your volume and your easy training is making it difficult to properly execute hard sessions or to accumulate more volume, then it could be a good idea to lower the intensity of that easy training, the way I did.

High-intensity zones

My main (actually, only) concern for high-intensity zones is Z3, as this is marathon pace, and I do love running a hard marathon once in a while.

For Z3, finding the the upper limit wasn’t straightforward, and required quite some trial and error, based on very long tempo runs and marathons, something I discuss in greater detail here.

In short, I prefer actual performance to dictate the limit, instad of lab tests. It is quite irrelevant to know where my lactate is, if I cannot run the full distance because of muscular cramps or other issues. Using training data and performance data, I could find a sustainable heart rate for me, for the marathon distance. Eventually zone 3 ended up being ~10 bpm higher than zone 2 for me.

I don’t use any higher intensity zones (Z4 and Z5) in a prescriptive way. They are defined for the graph above but I do nothing with heart rate data during intervals or races shorter than the marathon: I go by perceived effort, typically targeting a certain external load (pace), and whatever comes out as heart rate will do. I have never gone on a run thinking of running in Z4 or Z5 or following heart rate during a session harder than marathon pace. I do a short or long interval session, which tends to be Z5 vs Z4, at least in terms of external load.

Other resources:

A brief history of the past 15 years of my training

Here is how my training intensity distribution has evolved, which might give you some useful pointers in terms of how zones and training intensity distribution change as we develop as endurance athletes.

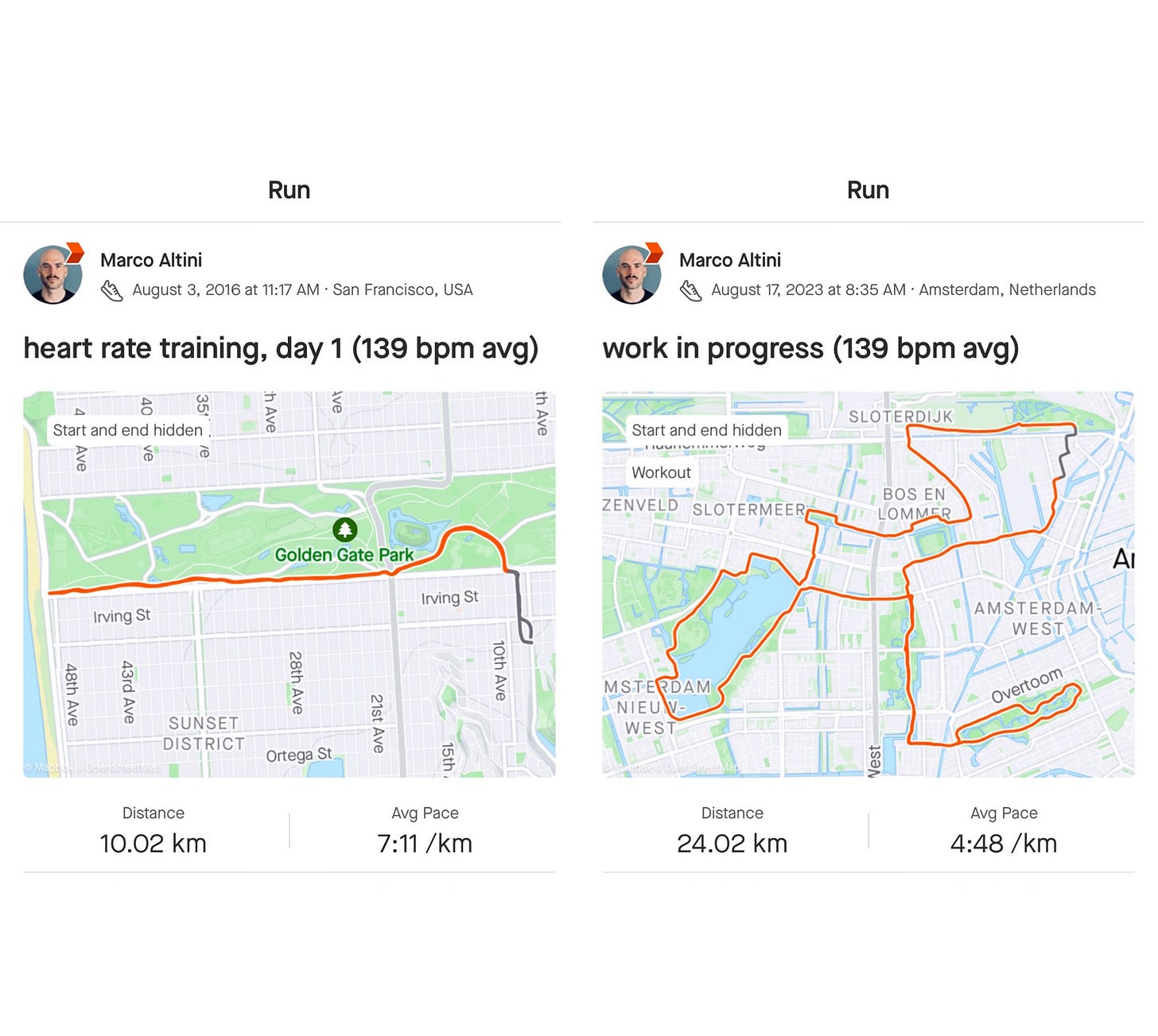

Back in 2016, when I started with low-intensity training, my pace was 7'11"/km (11'38"/mile) @ 139 bpm, or 75% of my maximal heart rate (and I had already been running for 6-7 years!). I am now running at ~4'48"/km (7'43"/mile) at the same, low heart rate. Thanks to Matt Fitzgerald and Stephen Seiler’s work, I slowed down, which then allowed me to be more rested, run more, and eventually make good progress over many years.

I never removed intensity from my training, it was always part of it for me. I do not believe in only training slowly, just so we are clear. While I had always done hard sessions, it was the easy training that I wasn't doing well or in a sufficient amount. I wasn't doing the easy stuff easily enough, and I got stuck there for years without progressing. Make no mistake, I thought I did go easy, it felt easy at that time, but it wasn't. As someone who started with endurance exercise relatively late, I had poor self-awareness of this type of effort.

Data (heart rate in this case) sometimes helps, e.g. if it's part of a bigger picture, and it leads to better awareness. I do not need heart rate now, but I did back then. I also do not necessarily think that this is the way to go for all, but it is likely applicable to others if the goal is to also increase training volume or run long distances.

I pulled some data from Strava to look at this visually, which I describe below.

Top plot, data collected in 2016, before starting with low-intensity training. I had been running already for 6-7 years: I was training with structure (hard workouts, etc.) but I had no awareness of effort or intensity as a late starter in endurance exercise. As a result, I was always training at moderate intensity. Hard training was there, but not supported by a good base. How do you recognize if you are in this situation?

Performance-wise, I could run fast intervals, but I could not hold that pace for a race. A huge gap between e.g. 1 km reps and half marathon pace. Running 1500 km / year.

Middle plot, data collected the first 6 months of more focused low-intensity training: starting to run at low intensity, it was really hard as I still had no aerobic base. All runs were more or less around what I deemed easy (e.g. 75-78% of maximal heart rate), you can see the peak of the distribution just there. Hard training was still part of the picture but there was more low-intensity training. I felt more rested between runs and I could step up my training volume (not visible in this graph). Over 6 months, training volume doubles (e.g. 30-40 to 70-80 km/week). Same amount of hard sessions or fewer, but more consistent easy training. Performance-wise, I quickly closed the gap between short reps and half marathon pace, but remained unable to run a good marathon. It was a short phase of re-focus on training intensity which led to quick improvements over distances between the 5km and half marathon, where I almost peaked in just 6 months. It will take many more years to improve my main weakness, running economy. Running 3000-4000 km/year.

Bottom plot, data collected in the past 6 months (end of 2023): I started being able to tolerate more easy training, and slowly move towards maximizing training volume. Fitness improves, and I find myself able to run while covering a very broad range of low intensities (Z1-Z2), see how wide the distribution is in the plot below. Easy training shifts towards lower and lower heart rates, and Z2 becomes too demanding (high external load), hence there is mainly Z1 now. I still do the same hard sessions, but average almost 6000 km / year, despite a few injuries and other issues (I am an average athlete, from a "genetic potential" point of view, these numbers aren't meant to impress anyone, they are only meaningful in relation to my journey, as context). The high volume, combined with specific workouts (e.g. lots of Z3 or marathon pace) finally improve my economy. Performance-wise, while my 5 km to half marathon times improve by very little with respect to 2017 (1-4 minutes), I take 21 minutes off my marathon personal best. My 1 km reps and half marathon pace now are really close. Running 5500-6000 km/year.

Performance and limiters

Analyzing performance over time, over different distances or workouts, can be very helpful to understand limiters and how to train if we have a certain performance goal in mind.

Top plot, February 2016 - August 2016:

1 km reps at 4'10"/km

half marathon time: 1h 45' (5'/km)

marathon time: unable to run more than ~25 km

Takeaway: VO2max is good, economy / durability is very poor (large gap between 1 km rep and half marathon pace, unable to run long).

Middle plot, August 2016 - February 2017:

1 km reps at 3'45"/km

half marathon time: 1h 28' to 1h 24' (4'10"-4'00"/km)

marathon time: 3h 20' (4'45"/km)

Takeaway: VO2max is good, economy / durability is improving, but still poor (closing the gap for the half marathon, but still very large gap between half marathon and marathon pace)

Bottom plot, April 2023 - October 2023:

1 km reps at ~3'40"/km

half marathon time: ~1h 21 (~3'50"/km)

marathon time: 2h 56' (4' 10"/km)

Takeaway: economy / durability has improved a lot (marathon pace much closer to half marathon pace), and is still the main limiter, but VO2max is now also a limiter (small gap between half marathon pace and 1 km reps pace). My performance ceiling is close.

For context, my performance goal is a 100 km race (together with a decent marathon here and there as I build towards the 100 km race), hence the shorter races here are just "side effects" of that training, they are not what my training is geared towards (if I wanted to run a faster 5 km or half marathon, I would train a bit differently).

This is key to understanding why I spend so much time on my legs and running slow: it is (in my opinion) helpful for that goal, to further improve my economy and durability, which have been my main weakness since the beginning (see below for proof, i.e. my energy expenditure at a given pace was the highest I had measured - and among relatively sedentary individuals -, while as runners, we want energy expenditure to be low, which means we are more economical).

Other resources:

When to use heart rate?

Heart rate for me is a key cap when facing a certain task. For example, during a marathon or an ultra, I know from experience such as previous races or race simulations that exceeding that cap will result in major drama (cramps or other issues leading to slowing down and not achieving whatever goal I had). During an easy run, heart rate can also be useful in a similar way, if I want to limit stress on the body, so that I can still accumulate high volume and make certain gains, without compromising high-intensity sessions or total volume.

Heart rate is often criticized because it doesn’t track external load, for example, it will be higher if it is hot. To me, that’s exactly the reason why it is useful. If I want to limit stress on the body or to race a certain distance and my body is working harder (i.e. heart rate is higher), then I better adjust my external load (i.e. run slower), or I won’t get to the end. Similarly, during an easy run, if I want to keep it easy and recover quickly, the internal load is what matters, not my pace.

For anything else (workouts, shorter races), I collect the data because I am curious about it, but I do not really look at it (I had no idea what my heart rate was during the recent half marathon personal best, I raced by perceived effort as always for this distance).

I will add that being limited from a muscular point of view, these days I always find myself training at a very easy internal load unless I am doing a workout, as otherwise I wouldn’t be able to sustain the volume, hence knowing my e.g. exact first lactate threshold (zone 2 limit) is not that useful to me anymore, because I very often train quite far from it (easier, or at a lower intensity, as shown by the graph above).

This will likely differ for others, depending on training age and key limiters (muscular or other). It also differs for me, on the occasions in which total volume is much lower (I would then naturally gravitate closer to z2).

My Zones

My maximal heart rate is 185-187 bpm, and here are my zones, based on the discussion above:

Z1: 100-135 bpm (most of my training)

Z2: 135-148 bpm (100 km race intensity for the low end, 50 km race intensity for the upper end)

Z3: 149-160 bpm (marathon pace for the upper end, tempo)

Z4: 161-172 bpm (half marathon intensity, mid-zone, or long intervals, upper end, not prescriptive)

Z5: 173-max (short intervals, not prescriptive)

In percentages:

Z1 55% - 72%

Z2 72% - 82%

Z3 82% - 87%

Z4 87% - 92%

Z5 92% - 100%

Is this the only way?

Of course not.

The shift to low intensity was the catalyst for me, but in my personal experience, a high volume of low-intensity training is key as a support for the higher intensity work, not just by itself. For example, in 2019-2021, due to many injuries, I could only train at low intensity, and while training volume was high, I was racing slower than I did in previous years. As soon as I could pick up intensity again (2022-2024), on top of the low-intensity volume, I could race personal bests again.

Keep in mind that there are many ways to go about it and improve as endurance athletes, and this is just one way, which I suspect worked for me also due to my "profile" (high VO2max, low economy, hence the need to train a lot at low intensities).

My partner has dramatically different physiology and makes progress while training very differently, which was quite an eye-opener for me. Individualization remains key, despite some basic principles being quite applicable across the board (train a lot, train hard sometimes).

What about lactate?

Over the years, I have tested lactate a few times, using the typical incremental protocols, as well as spot checks after holding the intensity more or less constant on a ‘real-life endurance run’ (i.e. outside, in the conditions I normally train, near what I would consider upper-end Z2). This latter type of test (a spot check after holding the intensity constant for a while) is probably more useful once our fitness is more or less stable and we want to better understand how things are going at the boundary between low-intensity and not-so-low intensity, so to speak. It’s also easier to do with respect to an incremental test, as you don’t need to do a maximal test. Additionally, looking at the point in which lactate production is higher than its removal, seems to be one of the most meaningful things we can do with this data (as opposed to looking at rather arbitrary absolute values, or fitting data to curves hoping to find a ‘second threshold’).

While I find it interesting, I don’t test lactate much, mainly because it’s not practical and a bit of a pain (quite literally). The inability or difficulty to collect data in realistic settings and continuously (the way you can do it with heart rate) makes it less useful, practically speaking (e.g. you can never check your lactate in a race, so you’d better rely on something else).

Additionally, with high training volume, I don’t really consider it necessary either as I naturally shift towards very low intensities for days in which I’m not doing a workout (I just can’t do otherwise, when maximizing volume, due to soreness, fatigue, etc - something I have discussed in more detail in the sections above), hence there is no “risk” of pushing intensity too much (if we want to call it that way).

For hard workouts, I don’t consider lactate particularly useful either (and it’s even less practical to test, given that lactate measurement should be taken after holding the intensity constant at least 6-8 minutes). Even if we believe a LT2 does exist (a questionable statement), there is no practical utility here. I prefer to set my boundaries based on what intensity I can maintain for a given distance, so that I can use these ‘zones’ while training or racing an event (e.g. as I discussed in previous sections, I consider Zone 3 marathon intensity, and use the top end of this zone as the upper limit of what I can sustain for a marathon, based on training and racing data - see also this blog). If my limiter is cramping, I need a practical tool that allows me to avoid cramping, regardless of my lactate being below maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) or else. This is why I must do a bit of trial and error (e.g. running long distances at race pace) and then adjust based on a sustainable heart rate (i.e. the maximum heart rate I can sustain without cramping). I cannot do any of this with lactate, with the currently available technology.

Let me try to rephrase this: lactate data might help us determine what we cannot do, more than what we can do. If my lactate is very high at what I consider a low intensity, it is unlikely that I can sustain that intensity for a 100 km race. However, if my lactate is not high, it doesn’t mean that there aren’t other limiters that will make it impossible for me to still complete the distance in the time I’d like to race. Lactate doesn’t determine what we can do (nor does critical power, or any other metric that comes from overly simplistic tests, especially for long or very long-distance running). Only race specificity in training - hard long workouts at race pace or race simulations - or racing can answer these questions.

When to test lactate then?

With low volume, there is a natural tendency to run always a bit faster (as we are fresher), and we do risk ending up running always the same, at moderate intensity (slightly too hard, which might result in compromising workouts and our ability to increase volume. This is why I wasn’t making progress for many years, as I cover here). In these cases, it might make more sense to test lactate and / or try to limit the intensity in other ways: we might learn that we need to keep heart rate lower to limit physiological stress on the body and be able to run more frequently or longer, eventually increasing volume (if the goal is also to increase volume… if we are otherwise happy with a low volume, then it’s a different story).

A lactate profile might be better than heart rate to determine this low intensity in which lactate removal can’t keep up with production, as this intensity might be at different percentages of our maximal heart rate, depending on a number of individual factors (training history, fitness, genetics, etc.). However, testing should be done in realistic settings, both for lactate and heart rate (there can be a large mismatch between lab data and your normal training, and things change for all sorts of reasons, try for example to test after eating more or less carbs and see what happens..), which again, is not always practical.

Protocol

As a simple protocol, I’d do something like running at a certain pace for 8-10 minutes, then measure lactate, and then do the same for a slightly faster pace, and once you start seeing lactate increasing more than 0.2-0.3 mmol/l, you are done. It’s simple and you can do it any day as the intensity is always rather low, since we are only trying to identify LT1. Often, instead of these incremental tests with long steps, I test after runs of 30-40 minutes at a ‘constant’ intensity, so that I don’t have to go to a track or bring my kit with me. In this case, you’d go at slightly difference paces on different days.

Recently, after a period in which I couldn’t run as much, as my legs felt fatigued after the 100 km del Passatore, I tested a few times following longer Z2 efforts (e.g. 1 or 2 hours at that intensity, while also drifting a bit in terms of heart rate, due to warmer weather). During this phase, which lasted about two months, I noticed I was getting slower, as expected, and my workouts were not where I wanted them to be. Cardiorespiratory fitness was getting worse. However, my training volume remained high (including cycling) and I was somewhat surprised to see that lactate levels wouldn’t move even after 2+ hours of running at high-end z2 (with a bit of drift, this would be almost 85% of my maximal heart rate, still at 1.6 mmol/l). Metabolic fitness was still good. In fact, it was better than it has ever been. I think these tests were useful. In case of a high lactate at the end of the z2 workouts, I would have changed training to more easy volume. But since it was low, I figured the easy volume was fine, and I could focus on the quality stuff, to improve cardiorespiratory fitness.

Personally, once in a while, I test simply because I’m curious or interested in seeing what’s changing with training (or detraining!), as it’s also part of my work, but I have hardly ever used the data to make large adjustments. This is mostly due to having trained many years, training high volume (and therefore far below LT1 on most non-workout runs), knowing at this point how certain intensities should feel, and having heart rate as a backup, which can still help me in certain situations. Heart rate was the main parameter I have used to make more dramatic changes to my training, as covered in this blog. Still, there can be meaningful ways to test and learn from the data, so that we can potentially make some useful changes, as I tried to elaborate above with an example on my training (Summer 2024).

I hope this gives you some useful pointers, thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Hi Marco,

That's interesting because now your training zones (in %) are similar to the Norwegian Olympic Committee 5 zone model. This model tends to be the one better appropriate for well trained individuals. However, you mentionned using 75/78% % of MHR at the beginning for your top end zone 2. This is more similar to the 5 zone model we see everywhere with Zone 2 below 75% MHR. Your article makes this point pretty clear : 5 zones model is interesting, but the percentages are changing depending on your fitness level, training history...

Really appreciate to read your blog post ! Have you found some correlations between between bigger than usual improvements and new training interventions (examples could be doing more volume on the bike, adding strength training, adding hill reps, fueling more ...) ?

Great information in this article! Thank you for sharing.

I have a question! 🙋

I performed a heart-rate drift test, which indicates that 140 BPM is the top of zone 2 for me. I find running at this heart rate for an hour to be quite uncomfortable! I even find it hard to speak in complete sentences at a heart-rate of 130-135. My ventilatory indicators and RPE seem very much out of sync with my heart-rate data.

I’m not a strong runner (a 10 minute/mile pace will put my heart-rate at 140 within 10-20 minutes), so the phenomenon of fitter athletes needing to do more of their “easy” volume in zone 1 is very unlikely to be at play here.

Here is my question: I am a heavier person at 185cm, 90kg, sub 10% body fat. Could the increased mechanical load required to run at this body-weight be the reason that the top of zone 2 feels so hard to me?

It seems like the only way I can run at the frequency I enjoy is to do almost all of my runs—other than speed work—in zone 1.

In your opinion, should I do all my “easy” runs in zone 1, and push the pace in my medium and longer aerobic runs towards the top of zone 2, even if it makes those routine aerobic runs feel like fatiguing workouts? Or should I keep ALL of my volume work at whatever pace feels easy, even if it is very much below the top of zone 2?