In a recent blog, I discussed temperature regulation during sleep and its impact on HRV and possibly recovery.

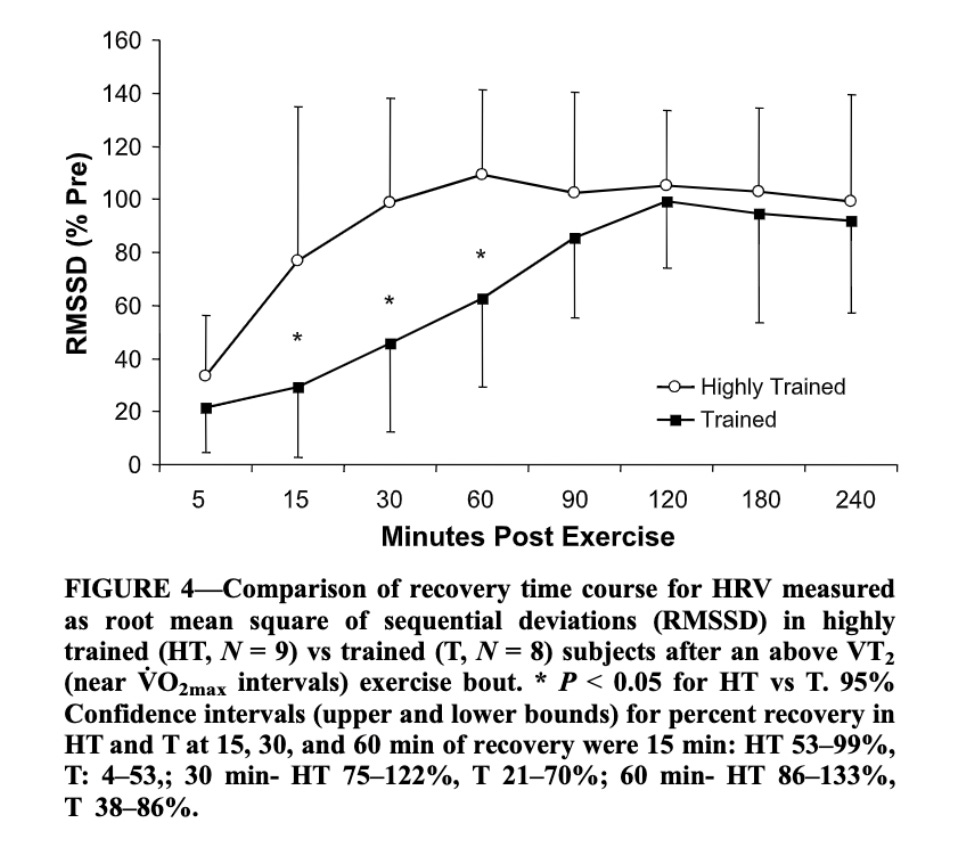

Something else that has intrigued me in the past few years is the possibility of using breathing techniques to stimulate HRV, and possibly impact recovery, e.g. by quickening a return to normal in terms of nervous system activity after high-intensity exercise.

We have seen in Stephen Seiler’s research (full text here) how after a hard workout HRV is suppressed: the body’s stress response causes the autonomic nervous system to increase sympathetic activity, and reduce parasympathetic activity. In turn, the autonomic nervous system impacts heart rhythm, reducing its variability, which we can measure with a HRV monitor (for a primer about HRV, go here).

If we look at HRV after workouts of different intensities, this is what we see:

Easy workouts (below the first ventilatory threshold) should lead to an immediate normalization, while hard workouts can take several hours for HRV to renormalize. This explains also why night HRV measurements and morning HRV measurements can differ: night data can be more tightly coupled with your behavior and what you did before going to bed, as the measurement comes earlier, while morning data will be more representative of your readiness for the day, as it comes after the restorative effect of sleep (deeper discussion, here).

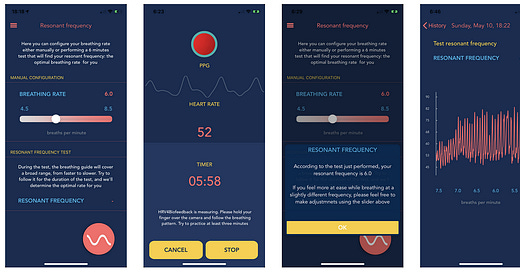

Now we look at the same data, but grouped by athlete’s fitness level:

In the figure above we can see that the renormalization of HRV after a hard effort is much quicker for highly trained individuals.

Stability (which is our goal) is reached earlier. A common question I get in podcasts or interviews is if we should expect our HRV to sink after hard sessions or (some companies even promote this idea). The answer is a resounding no. Highly trained athletes, experiencing the same hard workout (as intensities are relative to their ability) will recover and renormalize quickly: they reach an optimal state of stability before less trained athletes. A suppression normally follows a mismatch between the intensity of the session and our abilities (i.e. we went out too hard, more typical of recreational than professional athletes) or highlights the presence of non-training related stressors.

Following this line of thought, and adding some knowledge about how HRV biofeedback can improve HRV acutely, we could speculate that deep breathing exercises might favor a quicker re-normalization of our resting physiology, possibly leading to a faster recovery from an autonomic nervous system point of view (you’ll still be sore, recovery is multifactorial).

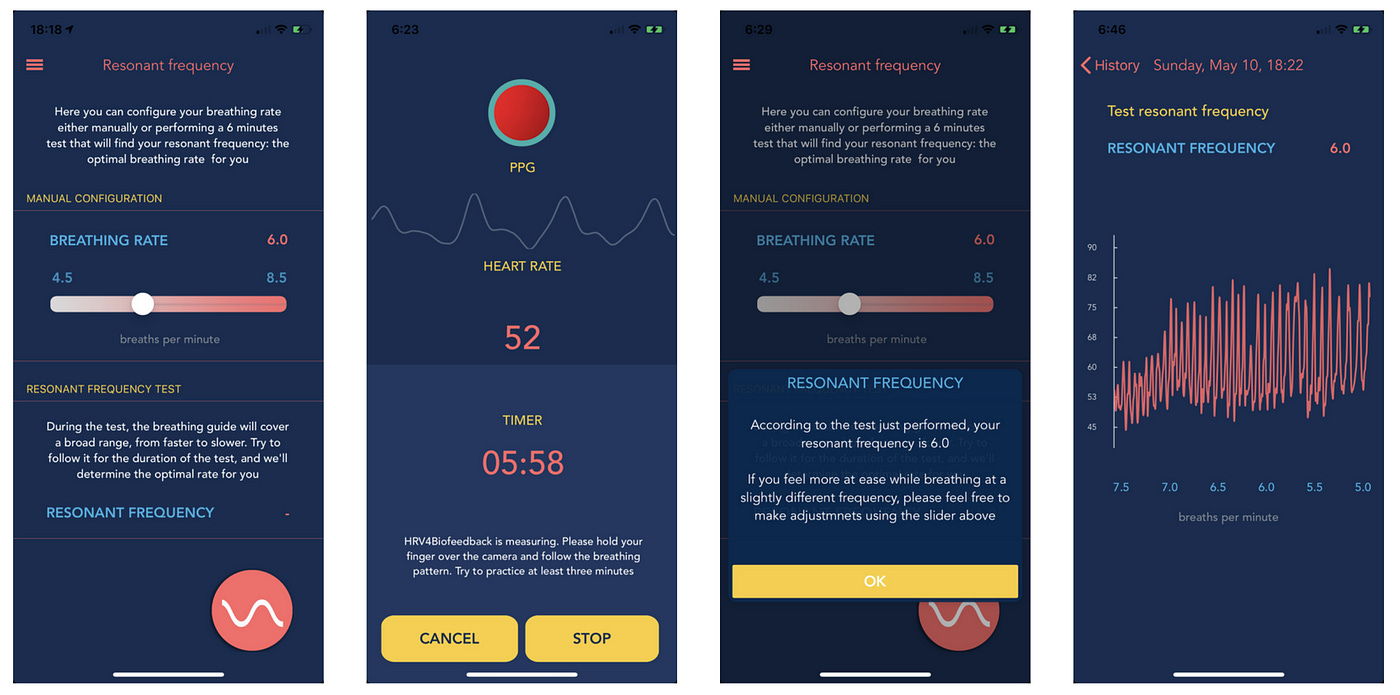

Slow-paced breathing, also known as resonance frequency breathing, involves deliberately slowing your breath to around 5-7 breaths per minute (see our HRV4Biofeedback app, which also helps you find your resonant frequency, which is the breathing rate at which your HRV is maximized). This helps create a state of physiological coherence, where heart rate and breathing synchronize. This technique directly engages the parasympathetic nervous system—the "rest and digest" system—which leads to an acute increase in HRV. After intense exercise, when the sympathetic nervous system (responsible for "fight or flight" responses) is still overactive, slow-paced breathing may help the body transition back to parasympathetic dominance, promoting faster recovery. Or at least, this is a hypothesis that I’d love to test at a larger scale (if you have tried it, feel free to comment below!).

Speculatively, we might view slow-paced breathing as a manual override for the ANS—a way to intentionally slow the heart rate and calm the nervous system, similar to the relaxation benefits of more sleep or naps. After high-intensity workouts, the body often remains in a state of heightened alert, with elevated heart rate and stress hormones. By incorporating slow-paced breathing into a cool-down or during rest periods, athletes might be able to return to a relaxed, recovery-focused state. Over time, this could potentially reduce recovery duration and improve training consistency by allowing the ANS to recover more swiftly.

What does the research say?

In a pilot study years ago we helped explore this technique with athletes using the HRV4Biofeedback app to practice deep breathing exercises after training. Athletes measured their resting physiology each morning using the HRV4Training app, according to best practices, to assess any changes in resting physiology outside of practice (keep in mind that HRV must be assessed at meaningful times, i.e. first thing in the morning, to avoid the issues I cover in detail here - hence we need to couple our intervention / deep breathing exercises with more typical morning measurements of our resting physiology, if we want to assess its effectiveness).

While this was a small, unpublished master’s student project, athletes who performed biofeedback showed a lower coefficient of variation in HRV compared to a control group that did not. A lower coefficient of variation indicates a more stable day-to-day physiological response, which is associated with better recovery profiles.

Recently, another study examined the effects of HRV biofeedback on short-term recovery after aerobic exercise. It found that participants using biofeedback during recovery showed improvements in HRV, indicating enhanced parasympathetic activation compared to those who did not use biofeedback (Yilmaz et al., 2024). However, these findings contrast with yet another study, which found that while HRV increased during the biofeedback session, it returned to baseline afterward, similar to the control group (Perez-Gaido et al., 2021).

Something I’d be curious to explore more, maybe in specific settings (e.g. after certain types of workouts), and in relation to various aspects of our stress response (e.g. not only increased HRV, but also, and possibly most importantly, improved stability).

In terms of a potential protocol, I think that it would be best to practice deep breathing towards the evening, maybe even before bed (this might give additional benefits as there is some evidence of improved sleep quality with biofeedback before bed). In any case, I would do it after exercise, as the idea is to shift the balance from a highly sympathetic state to a more parasympathetic one. In my experience, it can be difficult to practice slow deep breathing right after exercise or in the hours following exercise, when we exercise at high intensities. Hence I would try later in the day (evening or before bed). Then see if your morning HRV remains more frequently within your normal range, a sign of stability and of a better response.

Food for thought!

Case study: morning vs night HRV and using low-intensity exercise and slow, deep breathing to (possibly!) aid recovery

In this blog, I tried to put together an example of a few things I’ve discussed in recent posts and notes, to make it all a bit more practical.

Endurance Coaching for Runners

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and fill in the athlete intake form, here.

How to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

As a HRV4Training user, the best way to help is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you for supporting my work.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching. He is a certified Ultrarunning Coach.

Marco has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, Endurance Coach at Destination Unknown, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Applauding your exploration of these techniques, documentation is badly needed to support alternative complementary medical practitioners trying to convince patients of the link between sympathetic bias and chronic illness. I am an ex chronic fatigue sufferer, my Oura ring was a help, along with heartmath, in detecting my sympathetic bias problem. One thing most don't know is that extreme breath holding provides an automatic 'reset' for the heart's respiratory sinus arrythmia that lasts for a little while. This is the logic behind Buteyko method breathing retraining: breath holds after light exercise to lower heart rate and stimulate RSA, along with regular practice of resonant breathing with progressive muscle relaxation for dampening sympathetic bias. Buteyko practitioners also teach lifestyle changes to reduce stress because of the link between chronic hyperventilation and stress. This is also true of trauma recovery, the amygdala is basically an emotional memory bank with chemosensors that are triggered by rapid breathing. Kudos to you my friend, you are on the right track.

A timely post for me. I have been using some breathing exercises right before I go to bed - trying to get my heart rate down to below 50. My HRV is getting much better over the past 3 months - I am using the Oura ring to help me.