Should you measure your heart rate variability (HRV) on race day? What’s an ideal response in the days leading up to the race and on race day? How well do readiness or recovery scores reflect our ability to perform on race day?

In this blog, I’ll try to answer these questions, based on published literature and the past 10 years of experience working with this type of data.

Let’s see how far we get.

Context

First of all, we should recognize that both tapering and racing are outliers: something that happens rarely. Additionally, we can taper in many different ways (depending on the duration, volume reduction, or intensity management, for example). Similarly, a race might be more or less important or require different logistics (e.g. we might need to travel across the globe, or it could be just in our hometown).

All of these factors, together with the type of sport practiced, the profile of the athlete, the level of the athlete, and other circumstances, will impact the physiological response to tapering and race day.

While we will start by looking at the research, note that often there is a difference between research and real life: in research studies, participants typically do not see the data collected, and therefore the psychological component can change quite a bit in terms of the impact on performance. While this approach allows us to study the relationship between the physiology and race performance or even psychological stress (e.g. via additional questionnaires), we also need to think about the potential impact of looking at the data.

All of this makes it quite challenging to generalize, but let’s start by looking at published literature.

What does the research say?

I will split this section between tapering and race day, as they are often investigated separately in the scientific literature.

Tapering

Common sense says that during taper, HRV should increase. After all, this is when we finally start reducing load so that we can be ready to perform. In a few studies, the expected relationship between load and HRV has been observed: training load increases up to a point, leading to reduced HRV, then during taper, HRV rebounds. This makes sense as the load was already having a strong impact on the athlete’s physiology, possibly to a point in which a negative response was already reached (reduced HRV). This is the case for athletes of different levels [1, 2, 3].

It is important to highlight, however, that reduced HRV during increased load is not the response we normally target or hope to see. Increased load, when coping well with training and responding positively, should result in a stable or increased HRV. As a matter of fact, functional overreaching is associated with increased HRV, despite high load [2]. Recent studies [4, 5] have however shown the opposite relationship: reduced HRV with reduced load during tapering. Notably, this reduction was associated with world-class performance, highlighting how the reduction was not detrimental to performance. Why does this happen? The reduction in training volume might elicit lowered blood plasma volume and therefore decreased stroke volume, and in turn, increase heart rate and reduced HRV [4]. This reduction in HRV reflecting reduced parasympathetic activity and increased sympathetic activity during tapering could be potentially linked to a better physiological state in the context of competition (i.e. readiness to perform). This is typically the case for well-trained or elite athletes, where HRV has been trending well during periods of higher load.

Another reason for HRV to reduce could be associated with a suppressed heart rate during periods of high load. As we taper and reduce load, resting heart rate increases, re-normalizing, from the acute fatigue state in which it is often suppressed. As such, HRV will also decrease a bit. This is similar to the behavior of exercise heart rate, which might stay suppressed during periods of high load, as a sign of fatigue, but increase faster when reducing load or tapering.

These cases are quite different from rebounding from a period of suppressed HRV due to a poor response to a high load. Finally, a reduction in HRV following functional overreaching has been documented in other studies [5], where HRV remained relatively elevated, but lower than during a previous phase of higher training load, somewhat consistent with the studies previously mentioned.

See also:

Race day

There is less research when it comes to looking at HRV on race day, and therefore here I will add studies that do not necessarily concern only endurance athletes. In particular, when it comes to race day, the focus shifts from changes in physiology due to training (e.g. reductions in volume or plasma volume that could explain changes in HRV) to psychological factors.

In a study on elite BMX riders [6], a strong inverse correlation has been reported between anxiety state and morning HRV. Greater scores for the somatic and cognitive anxiety sub-scales were associated with reduced parasympathetic activity as measured by HRV. The same results were shown in another two studies in swimmers [7, 9], where anxiety was also inversely related to rMSSD, a marker of parasympathetic activity. In all of these studies, data was collected on different occasions, i.e. once before training, and once on race day. This is not ideal in my view, but it was the norm when longitudinal data collection was not as easy as today.

Another study looked at HRV during competitions of different levels in football players [8]. Consistently with the previous studies, there was an association between pre-game anxiety and reduced HRV, and this association was only present for important matches, while no change in HRV was reported for low-demanding matches.

Most of the studies above report higher anxiety and reduced HRV on the most important occasions, and extrapolate to this state being a negative one, which might need to be addressed to reduce anxiety and (possibly) improve HRV on race or game day. However, it should be noted that all the studies discussed so far look at the relationship between anxiety and HRV, but stop there. They do not look at performance.

In only one study I could find the relationship between race day HRV and performance is investigated. In [10], elite long jump athletes were measured before the Olympics games. Interestingly, the most successful performers had the largest suppressions in HRV. This is maybe unexpected, as all the previous studies suggest that certain interventions should take place to reduce anxiety on race day (and supposedly also increase HRV), while in the one study that looked at performance, having a better HRV on the most important day did not seem important, quite the contrary. This is only one study and a few athletes, but still, it challenges some of the assumptions brought up from the previous studies. In the words of the authors, "we hypothesize that there is an increased requirement of sympathetic .. activity, indicated by lower HRV, necessary for successful performance by elite athletes in major competitions".

In [4], weekly moving averages leading up to the world championships and Olympics are shown for a group of rowers, whose HRV is reducing (as per the previous section on tapering). However, no daily data is shown, and therefore it is difficult to extrapolate and understand if a suppression was present on race day too. However, in the study just discussed above [10], the strongest relationship between race day performance and HRV is not with race day HRV, but with the HRV baseline of the week preceding the race, what we could consider “taper HRV”, consistently with the study of Plews et al. [4].

Research takeaways

Positive responses to increased training load should result in stable or increasing HRV. This increase in HRV is associated with a functional overreaching state which is also reflected in reduced resting heart rate and exercise heart rate. However, during this phase, performance can be impaired (due to the high load).

Following this phase and response, during tapering, we might have a drop in HRV. There could be multiple reasons behind this reduction in HRV, as covered in Daniel Plews’ research, for example, reduced plasma volume due to less aerobic stimulus, parasympathetic saturation, or simply the race getting to you.

This reduction might extend or be amplified on race day, due to anxiety, and seems to have no implications for performance.

On the other hand, If your training has been less than optimal or your HRV has been often below normal, you might see a rebound and increased HRV with tapering, as most likely a reduction in load was long overdue.

The research tells you that you should not worry about a reduction in HRV during race week or on race day. Obviously, if you are feeling poorly, eating random things in airports, sleeping poorly, maybe getting a bit sick, etc. - the data will capture that too: not all reductions will be representative of a good taper or the right type of race stress. Context remains key.

Readiness and recovery scores

In general, my recommendation is to always look at the physiology, and not bother much with scores built on top of the metrics, for reasons I discuss in more detail here.

Scores make assumptions: you exercise more or sleep less and you are penalized. However, your physiology might be perfectly normal, and that’s what you want to look at, especially in the context of training. Learn to look at the actual data and to use tools that allow you to easily understand if a daily measurement is within your normal range or not.

On race day in particular, the issue of combining behavior with physiology becomes even more problematic, as sleep is often either shorter or more disrupted prior to a race, and therefore readiness or recovery scores fail. The relationship between sleep and HRV is also not obvious, and likely individual, hence the assumptions made to generate a readiness or recovery score, might not be applicable to you (maybe your HRV is in fact still within normal range).

When it comes to training, I need to know where my physiology is, without the confounding effect of my behavior.

See for example the message I have received on the mornings of my last marathons PR, despite a normal HRV (the exact wording is quite funny on this occasion):

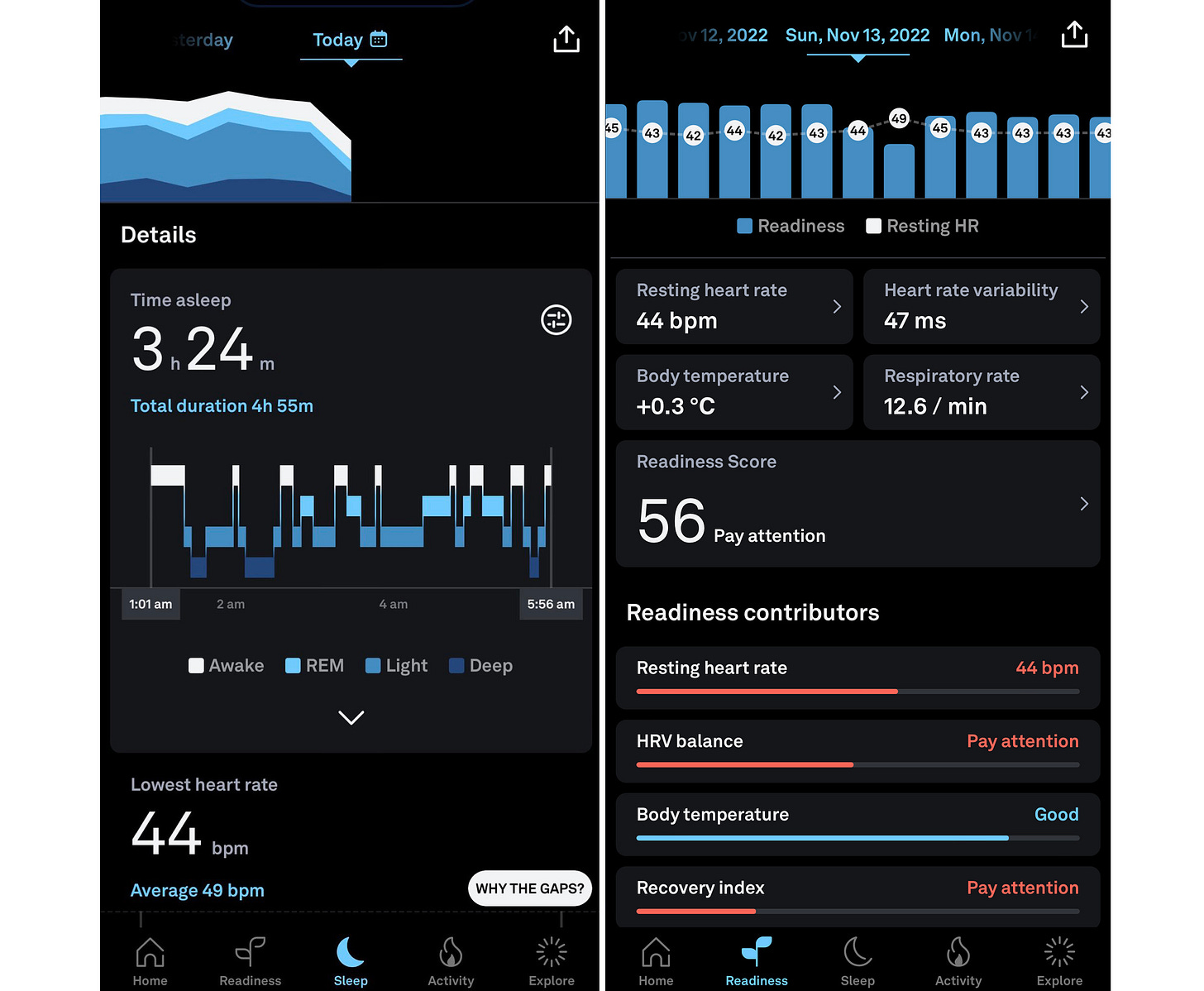

On another occasion (the previous marathon PR), I was coming from a high stress phase: traveling, giving talks and being sick just before. Additionally, I was much more stressed about the race, and barely got any sleep:

Poor sleep in this occasion is the same as low HRV: it does not define in any way what you can do on a given day, but it still matters. Why? Because if you chronically are sleep deprived and / or your HRV is chronically suppressed, your health and performance are compromised. The data is still helpful but does not determine what you can do on a give day.

This is why it makes little sense to build readiness or recovery scores, despite the fact that the physiology is useful to keep track of how you are doing over time.

A final note I’d like to add here is on the measurement protocol: measuring in the night will impact the data more than measuring in the morning, especially if your sleep is poor or disrupted. In these cases, a morning measurement might provide a better representation of your state, in my opinion.

Hide your data in HRV4Training

On race day, you are racing. You might be curious about the data, maybe especially after reading about the relationships shown in the research discussed above, but if you are concerned that a suppression in HRV might impact you psychologically, simply hide your data.

To do so in HRV4Training, you can choose “Compeeting | Hide HRV” in the Training Phase tag of the questionnaire (you can choose which tags to use from Settings - Configure Tags). The app will not show you any data after the measurement, and the History and Baseline pages will also be empty.

Post-race

There is even less data on this, maybe none when it comes to looking at different races for the same person over time, but this is something where we all have collected plenty of data and I would like to add just some pointers based on my experience.

In particular, while race week trends and race day values might not impact your performance, they tend to impact your recovery and what you can do in the weeks after the race. This has implications depending on how dense is your racing season.

This is the whole point of HRV-guided training: you can in most occasions perform on a low HRV day (assuming you are not sick), but your ability to positively assimilate the stimulus can be compromised. This is why studies have shown better performance for athletes skipping hard sessions on low HRV days. On race day, you can still perform, but your recovery might be compromised. This is quite clear in my experience, where racing when in a good HRV trend is something I can bounce back from quickly (marathon PR on April 16th, small suppression the day after, then back to normal):

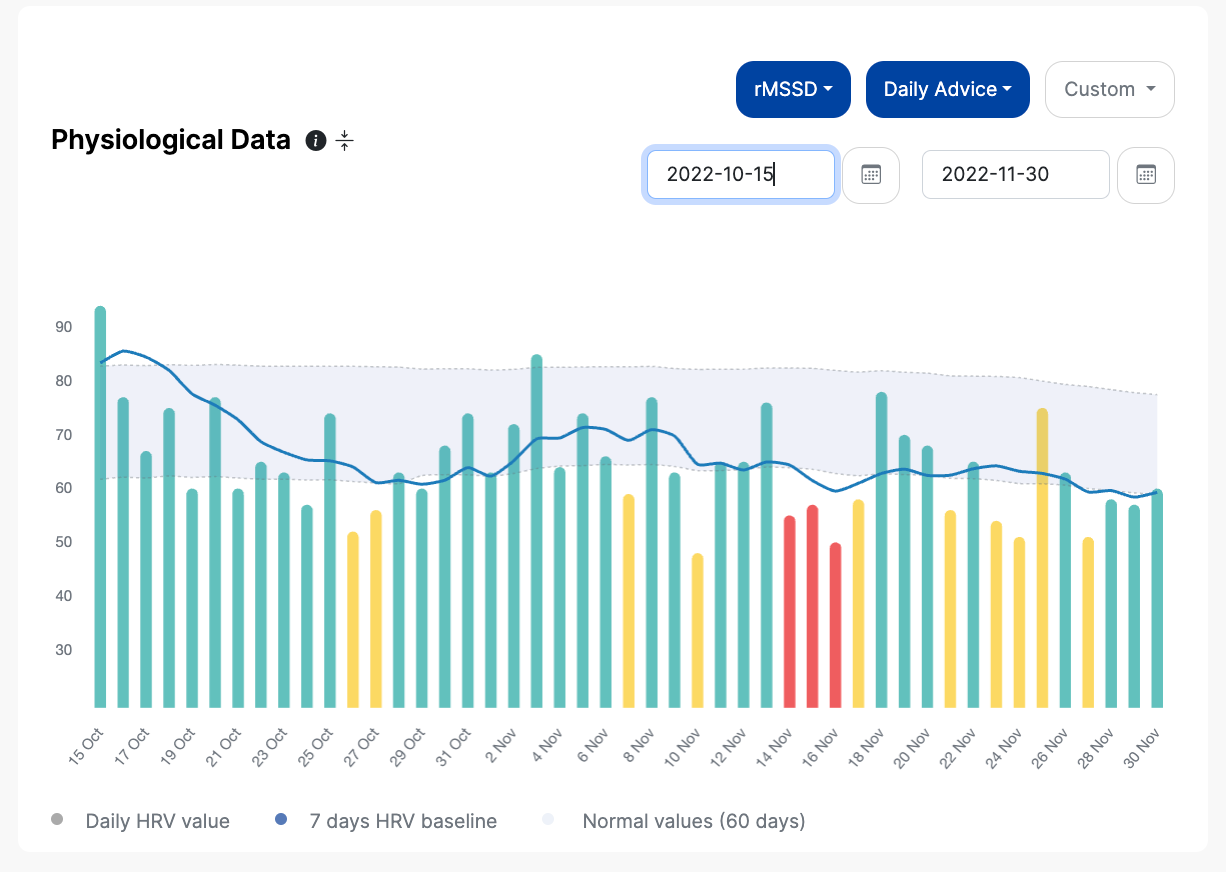

While when I was already in a hole (travel and work stress, sickness in the weeks prior to a marathon on November 13th), then took a lot longer to come back (several days with suppressions, then the baseline also slowly going outside of the normal range):

This data can then help you deciding what to do, e.g. if you are in a phase in which more frequent racing can be handled well by your body, or if you are in a phase where you might still want to race your main event, but then take more time before the next event.

I hope this was informative, and thank you for reading!

References

[1] Flatt, A. A., Hornikel, B., & Esco, M. R. (2017). Heart rate variability and psychometric responses to overload and tapering in collegiate sprint-swimmers. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 20(6), 606–610.

[2] Le Meur, Y., Pichon, A., Schaal, K., Schmitt, L., Louis, J., Gueneron, J., … & Hausswirth, C. (2013). Evidence of parasympathetic hyperactivity in functionally overreached athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 45(11), 2061–2071.

[3] Iellamo, F., Legramante, J. M., Pigozzi, F., Spataro, A., Norbiato, G., Lucini, D., & Pagani, M. (2002). Conversion from vagal to sympathetic predominance with strenuous training in high-performance world-class athletes. Circulation, 105(23), 2719–2724.

[4] Plews, D. J., Laursen, P. B., Stanley, J., Kilding, A. E., & Buchheit, M. (2013). Training adaptation and heart rate variability in elite endurance athletes: opening the door to effective monitoring. Sports medicine, 43(9), 773–781.

[5] Bellenger, C. R., Karavirta, L., Thomson, R. L., Robertson, E. Y., Davison, K., & Buckley, J. D. (2016). Contextualizing parasympathetic hyperactivity in functionally overreached athletes with perceptions of training tolerance. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 11(5), 685–692.

[6] Mateo, M., Blasco-Lafarga, C., Martínez-Navarro, I., Guzmán, J. F., & Zabala, M. (2012). Heart rate variability and pre-competitive anxiety in BMX discipline. European journal of applied physiology, 112, 113-123.

[7] Blásquez, J.C.C., Font, G.R. and Ortís, L.C., 2009. Heart-rate variability and precompetitive anxiety in swimmers. Psicothema, pp.531-536.

[8] Ayuso-Moreno, R., Fuentes-García, J.P., Collado-Mateo, D. and Villafaina, S., 2020. Heart rate variability and pre-competitive anxiety according to the demanding level of the match in female soccer athletes. Physiology & behavior, 222, p.112926.

[9] Fortes, L.S., da Costa, B.D., Paes, P.P., do Nascimento Júnior, J.R., Fiorese, L. and Ferreira, M.E., 2017. Influence of competitive-anxiety on heart rate variability in swimmers. Journal of sports science & medicine, 16(4), p.498.

[10] Coyne, J., Coutts, A., Newton, R. and Haff, G.G., 2021. Training load, heart rate variability, direct current potential and elite long jump performance prior and during the 2016 Olympic Games. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 20(3), p.482.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

I saw a huge decrease in HRV the week prior to the Boston Marathon. I attribute it to mental stress and anxiety about the race (and also poor sleep); however, I was able to do well in the race, setting a PR by over 5 minutes. In the weeks since the race, my HRV #'s are at the upper range, showing a strong recovery.