HRV-Guided Training: When To Hold Back and When To PUSH

Plot twist.

I’ve recently written about HRV-guided training, its origins, and how to use HRV to modulate training load.

While discussing this topic with Dan Plews, with whom I am writing a book (together with Emma Mosley and Sylvain Laborde - hopefully coming to you sometime next year!), Dan brought up some interesting papers showing a strong link between baseline HRV and training adaptations, highlighting how individuals approaching a period of training overload with a higher baseline HRV, would show much larger improvements with respect to individuals approaching an overload period with a lower HRV.

These articles (Hautala et. al., 2003, Hautala et. al., 2008 and Vesterinen et al. 2013) made me think more about the use of HRV and, in particular, HRV-guided training, where I tend to always stress its utility to hold back, more than to push harder.

This is something I’ve been thinking about a fair amount, especially since Jason Koop brought up to me the same question, while discussing HRV with his team at CTS a few years back.

In this blog, I would like to discuss the practical implications of the studies above and how we can try to use HRV not only to slow down, but also to decide when we can push harder, as we could obtain larger gains.

What You Know Already: Slowing Down

I won’t spend much time on this as I’ve discussed it plenty of times, but in short, the best case for HRV in the context of managing training load is to determine when to reduce load (see here for more details on what that means, i.e., volume vs intensity, etc.).

In practical terms, starting from a solid plan, built by you if you are self-coached, or by your coach, we want to use HRV to make small adjustments, reducing load when your body is unlikely to assimilate the stimulus. Without a solid plan and subjective feedback, there is no use for HRV as HRV cannot capture important parts of the recovery process (e.g., muscular breakdown - hence the meaningless information you get from ‘recovery’ or ‘readiness’ scores in wearables or apps).

I always stress this aspect of HRV guidance as there are various reasons to limit the number of high-intensity sessions, especially for sports where injury risk is particularly high, as in running. Thus, when we have built a training plan, we typically already have a number of high-intensity sessions that are near what we consider an acceptable limit for the athlete.

However, data in the papers above shows that not only more training won’t lead to the desired adaptations when HRV is low, but that the desired adaptations might be larger when HRV is high, hence this is something we might want to try to use to our advantage, at times.

Below, I revisit the topic from this different angle.

The Flipside: Pushing Harder

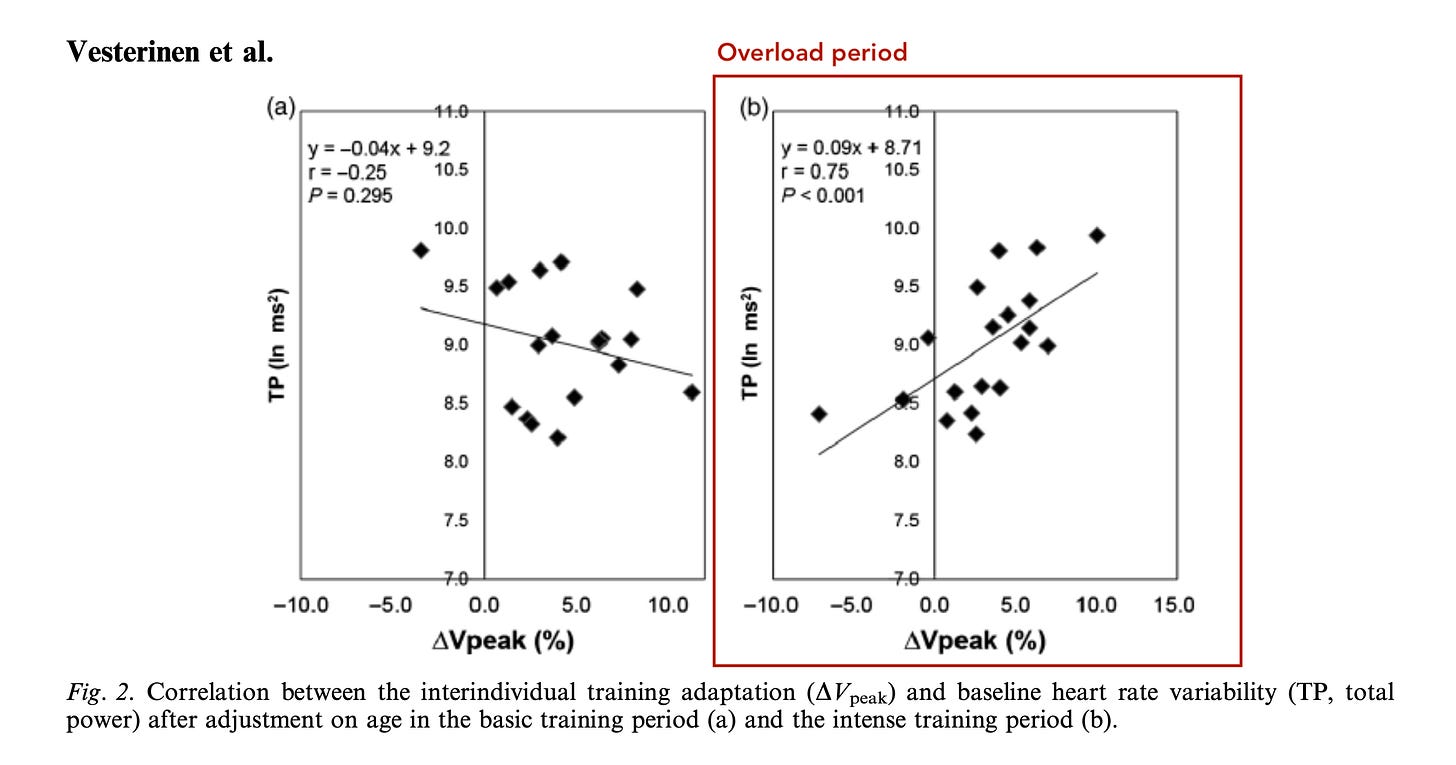

In the figure above, derived from the Vesterinen paper, we can see that individuals with higher baseline HRV when starting an overload period, improve more.

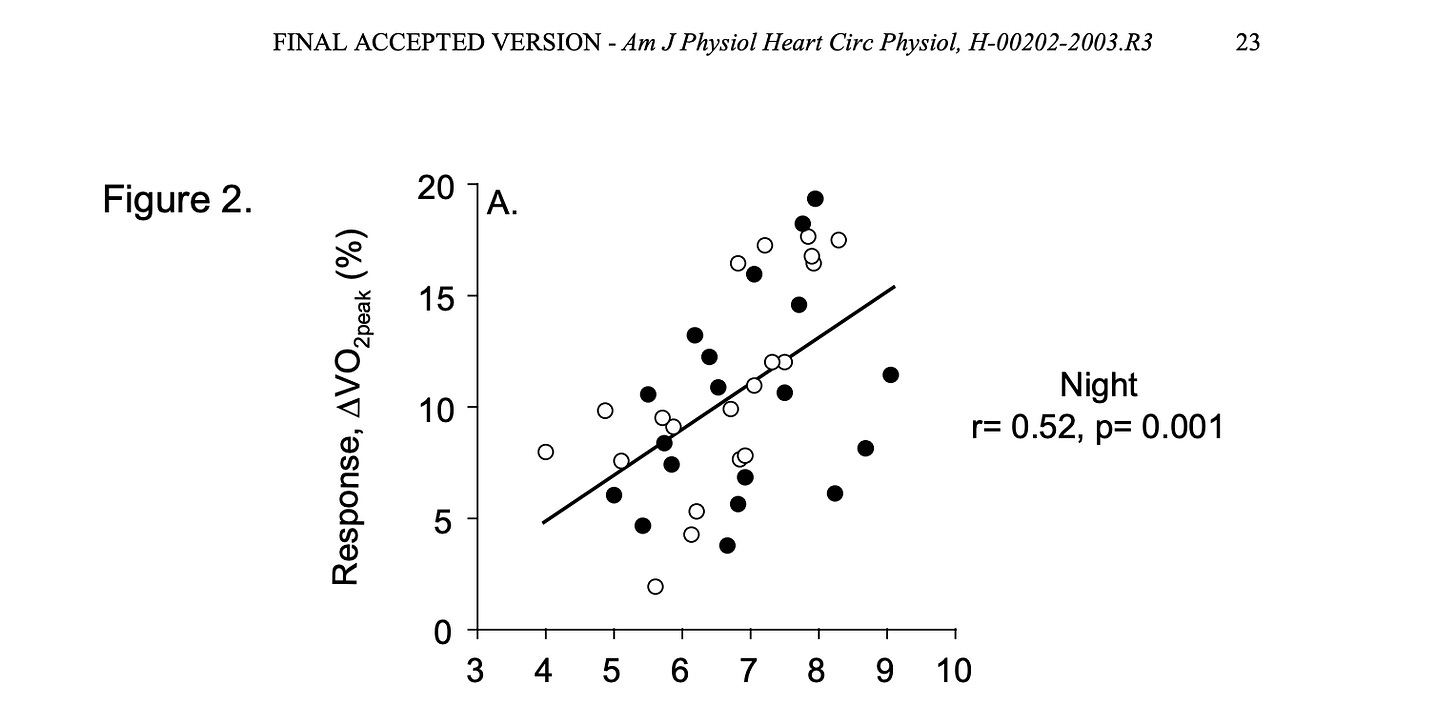

The same was shown by Hautala already back in 2003:

Quoting the authors: “These data show that cardiovascular autonomic function is an important determinant of the response to aerobic training … High vagal activity at baseline is associated with the improvement in aerobic power caused by aerobic exercise training …“.

I read these studies many years ago and always struggled with the fact that they seemed to highlight how we are genetically doomed, more than how we can use HRV to guide training, at least in my (always very optimistic) mind. If my baseline HRV is low, what can we do?

The other side of the equation, i.e., reducing training load when HRV is low, has been since then tested in longitudinal studies, assessing within-individual changes, and therefore we have all the evidence we need to establish that this approach is not only theoretically sound, but also practically feasible and effective for everyone, as the adjustments to implement are based on how your own HRV is changing over time.

We cannot say the same yet for the “pushing harder” side of things, meaning that the studies have looked at cross-sectional data and have not explored interventions in which individuals have been given higher loads when their HRV was trending higher, hence what follows is more speculative and mostly based on how I think about this and how I use it for myself or the people I coach.

Getting Practical

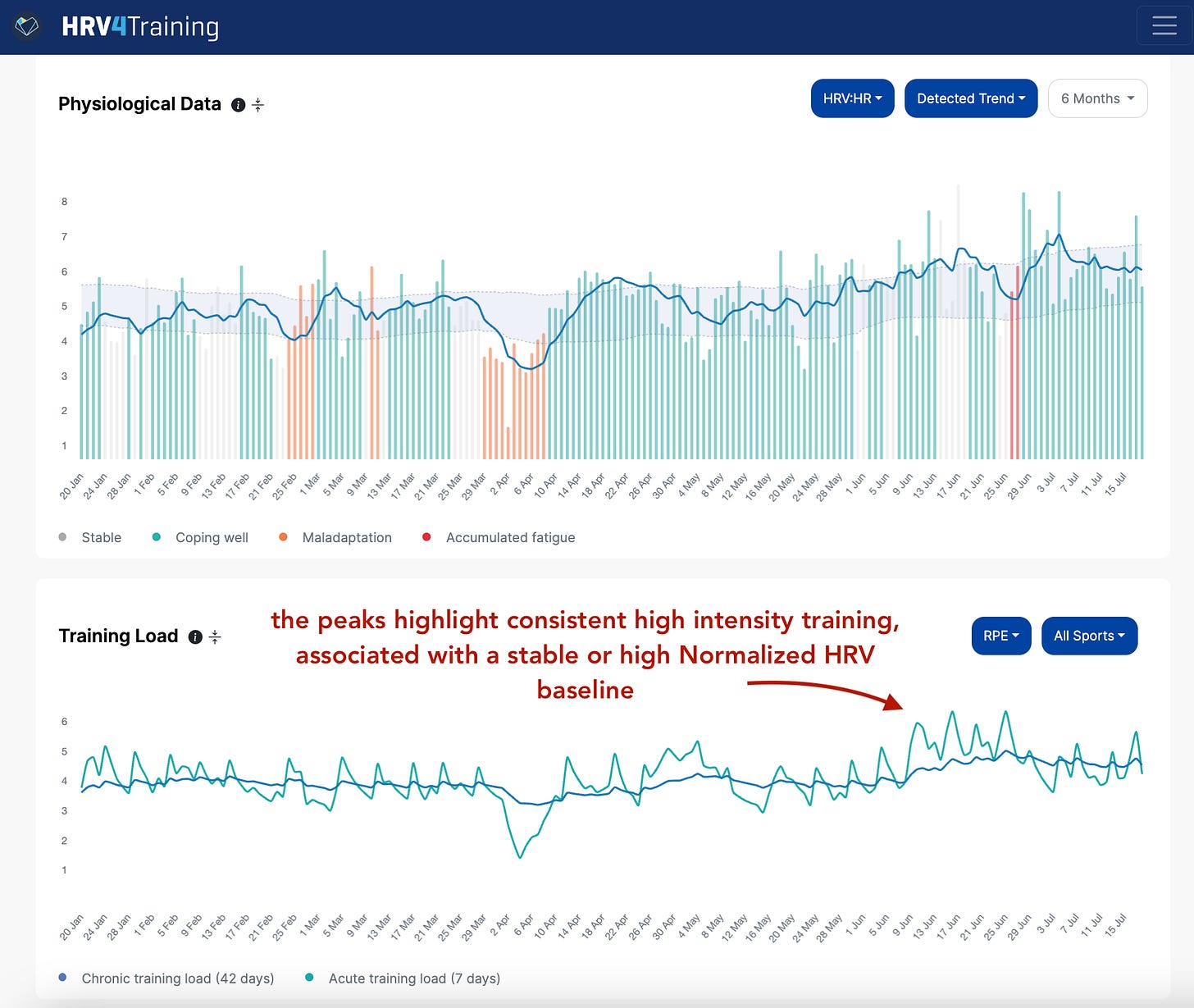

Below is an example showing my past 6 months of data, in terms of Normalized HRV and training intensity (based on RPE, the rate of perceived exertion). Apart from a short trip (end of February) and a bout of sickness (beginning of April) the data (baseline) has always been within normal range or trending towards the high end of the normal range.

Workouts reflected this stable and positive trend, as we can see from the many peaks in the RPE and Training Load plot, highlighting great consistency with high-intensity training. Interestingly, I did not proactively increase the frequency of high-intensity sessions because my HRV was high, but I simply did what my body allowed me to do, which seems to be well reflected in baseline HRV data as well (!).

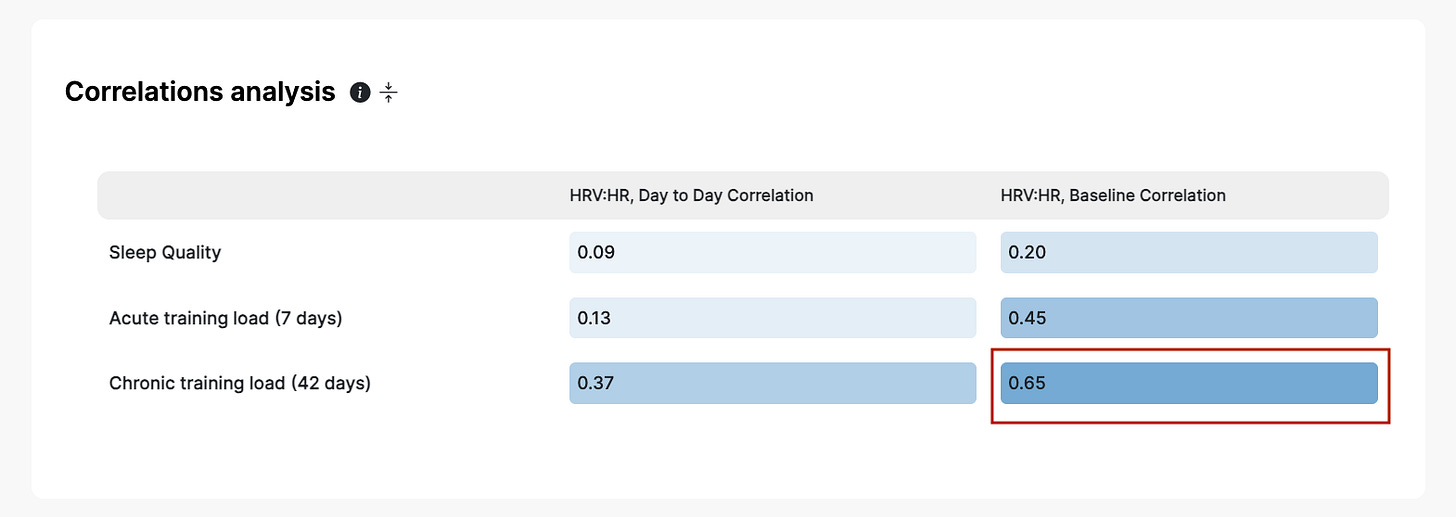

We can see this relationship quite clearly visually, as a strong correlation between Normalized HRV baseline (7-day moving average shown as a bluet line in HRV4Training Pro) and chronic RPE (the blue line in the training load plot) is present, but we can also look at the math on our web platform:

During these six months, my performance has been consistently improving, hence backing up the group-level data shown in the papers linked above (despite some setbacks such as the bout of sickness shown above, and an injury post 50km personal best, resulting in using different training modalities and getting more creative with training in the past month, aerobic fitness is as good as ever, which is the parameter of interest here as we are looking at a cardiac parameter - HRV - in the context of cardiac adaptations).

I will add that when looking at increases in HRV as a potential marker of what could be the ideal moment to increase training load, I think Normalized HRV can offer additional advantages, as we would not get fooled by changes in HRV that are simply due to a large suppression in resting heart rate (as in the case of fatigue!). You can see your own data for Normalized HRV in the Overview page of HRV4Training Pro.

Below is another example from an athlete I coach, whose data recently has trended in a similar direction, and therefore potentially allows for greater adaptations:

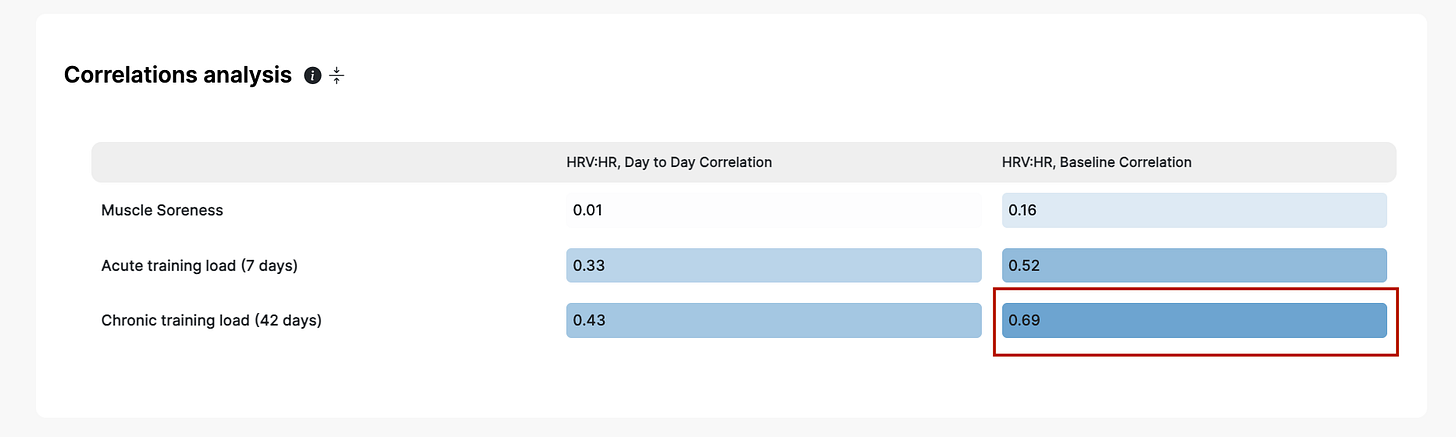

And similarly, also for this athlete, we have a strong correlation between chronic load in RPE and Normalized HRV, associated with performance improvements:

I’m highlighting long term data and correlations here because the approach I’d recommend is certainly not the one of waking up with a high HRV and deciding to ‘go hard’, but to look at long term trends, how the baseline is changing with respect to the normal range, and eventually deciding if we are in a training block where we could try to add a bit of density or not. This is not a reactive approach or making up training as we go. This is about integrating information and thinking long term.

Alright, that’s a wrap for today!

While recent research on HRV-guided training has mostly focused on reducing training load (typically, intensity), early work from more than 20 years ago gives us useful pointers to use the data in the opposite direction, i.e. to further increase load, aiming for additional adaptations.

Needless to say, a sound training plan and many additional considerations beyond HRV need to be part of the process here, to maintain our athletes (and ourselves) healthy and injury-free in the process. Additionally, the evidence covered here shows data collected cross-sectionally or at the group level, and does not investigate this approach in detail longitudinally, the way it has been done for HRV-guided training that aims at reducing load.

Yet, there seems to be a solid theoretical basis for this approach, and I’ve also reported a few cases of clear correlations between load and HRV for athletes who have been improving their performance during such periods.

Something more to experiment with, maybe.

In the meantime, thank you for reading, and all the best for your training!

Endurance Coaching for Runners

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and fill in the athlete intake form, here.

How to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

As a HRV4Training user, the best way to help is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you for supporting my work.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching. He is a certified ultrarunning coach.

Marco has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, Endurance Coach at Destination Unknown Endurance Coaching, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

One question I have is, what should we do when we have a yellow day on the morning of a hard workout, such as a track session (often for me, this is something like 5 x 1k at 5k pace). Assuming we feel more or less fine (that is, we don't feel awful but we don't feel amazing), what to do with the "limit intensity" recommendation?

One answer in my head would be, well, if the next day is a rest day, go ahead and do the track session and spend the next day working on recovery modalities.

But what if the next day is not a rest day? Should we do the track session on a day we're back within our normal range? Or do the track session, but limit reps?

I've always been unclear about this.