[TrainingTalk] 50 km di Romagna: Training, Nutrition and Race Report (2025)

A 10-minute personal best, closing in 3h 47' (72nd/1600)

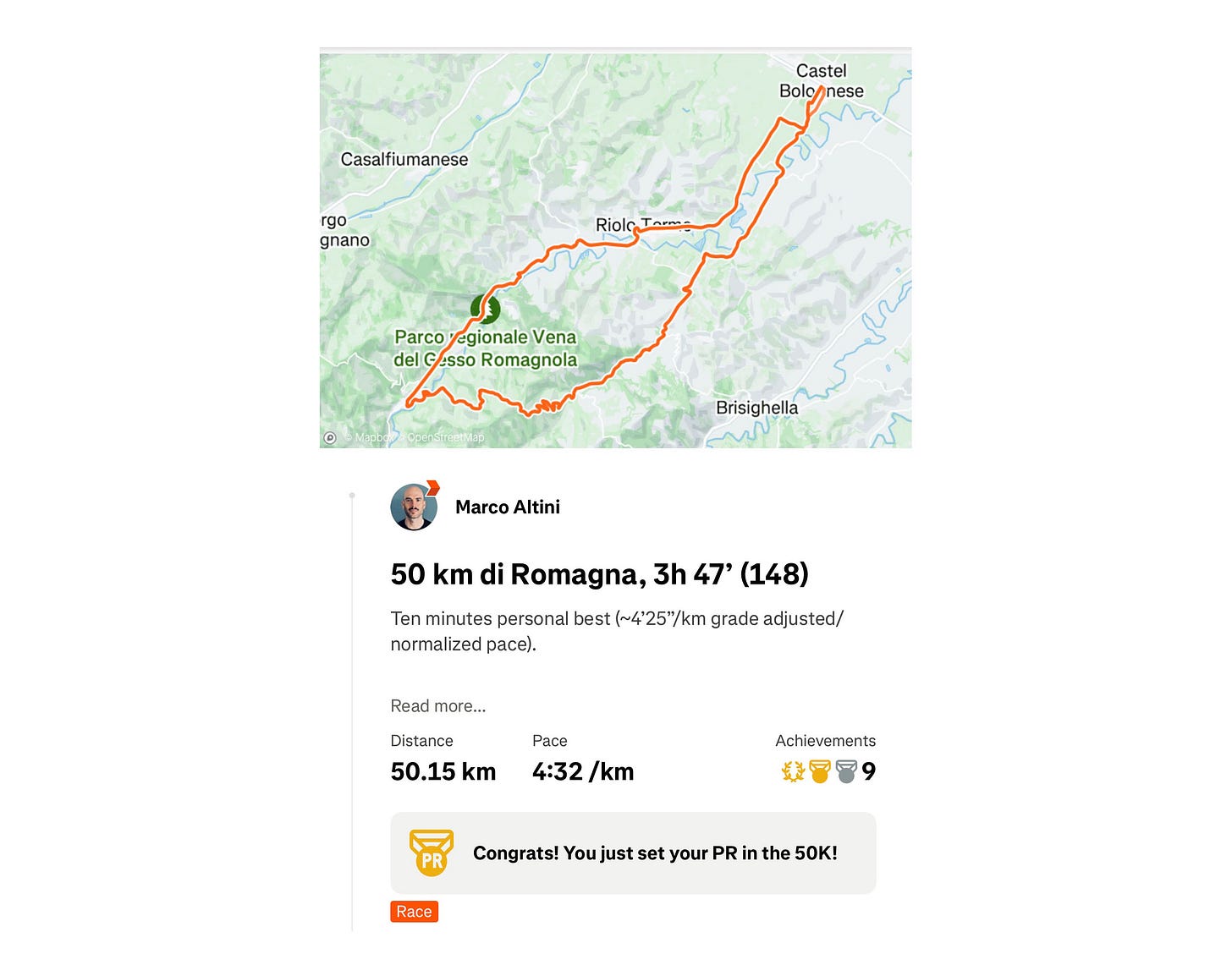

Yesterday I ran a personal best at the 50 km di Romagna, which is also the first personal best of my forties (gotta take the wins).

In this blog, I cover my preparation in terms of training and nutrition, including tapering, race day pacing, and fueling (oh my!).

The Training:

Running

Nutrition

The Extra (specificity, heat)

The Race:

Tapering

Pacing

Nutrition

Takeaways:

Breakthroughs

Progress is all about individualization

Training

Below, I cover the past 90 days of training. As you might know already, I have recently addressed limiters in my physiology with changes in nutrition more than training (discussed below).

Since the beginning of February, my body composition and nutrition have been stable, and I could therefore train well and prepare for my two A races before summer: the 50 km di Romagna and the 100 km del Passatore.

The Running

I am currently using a 3-week microcycle, which is modulated by how close I am to the main race of the year, in terms of specificity and types of workouts used. I opted for this approach to address some of my limiters (i.e., poor economy and durability, high rate of injuries), while trying to get better at the long-distance and remain injury-free. This means that I try to touch a bit of everything over 3 weeks: top-end speed, power, VO2max intensity, threshold, tempo/marathon pace, and lots of easy running at various intensities both on trails and roads. For me personally, this type of high-volume training, with sporadic high-intensity workouts (typically, just one proper hard workout per week, with smaller bits of quality here and there), leads to consistent progress in performance.

Below is an example of a good block of training:

Here are the totals for the past 90 days:

And here tis he intensity distribution:

The main change I made in training in the past 3-4 months is to include more training near my first lactate threshold (LT1), hence the large amounts of Z2 (second lightest color above), which tends to be at a much higher external load (read: speed, when running on flat roads), with respect to the remaining of my easy running (Z1, lightest color).

There isn’t much more to say about these three months of training: consistent high volume, consistent, sporadic high-intensity sessions, lots of specificity (covered in more detail below), and as few disruptions as possible (no travel, events, etc. in the past two months - just slow life in rural Italy - work, training, eating well, sleeping well, community, all the basic things we know matter).

Below is another way to look at this, with HRV mostly stable in my normal range, apart from a period of sickness. We can also appreciate a rebound above normal range during a high-volume training camp and a reduction during taper, something I discussed recently in this blog:

Nutrition

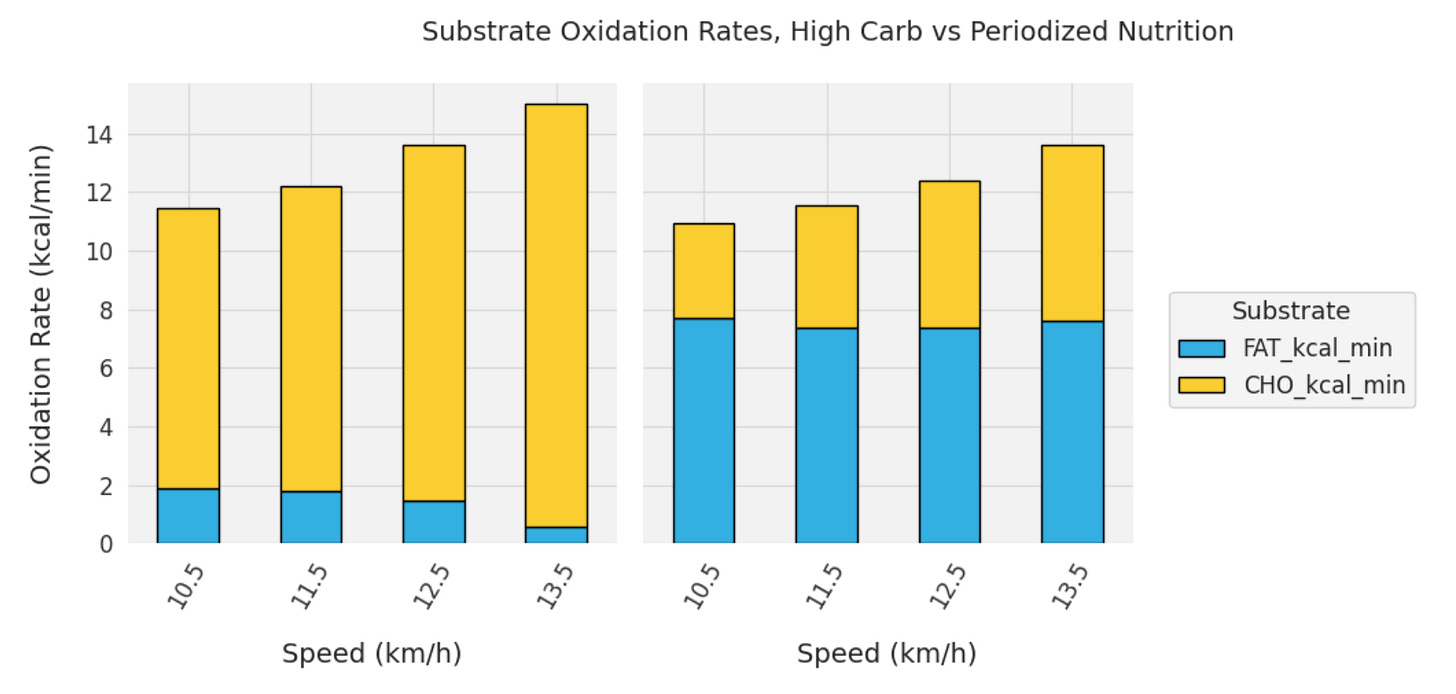

For these three months, I’ve kept up my periodized nutrition approach, which is covered in great detail here. In short, this is all about improving metabolic flexibility (i.e., sparing scarce resources such as glycogen, thanks to a greater reliance on fat as fuel, at any intensity, while also maintaining the ability to oxidize carbohydrates at very high intensities).

Poor fat oxidation and the resulting quick depletion of glycogen stores was a huge limiter for me, and probably one of the main reasons behind underperforming in long-distance events, despite "training more than most”.

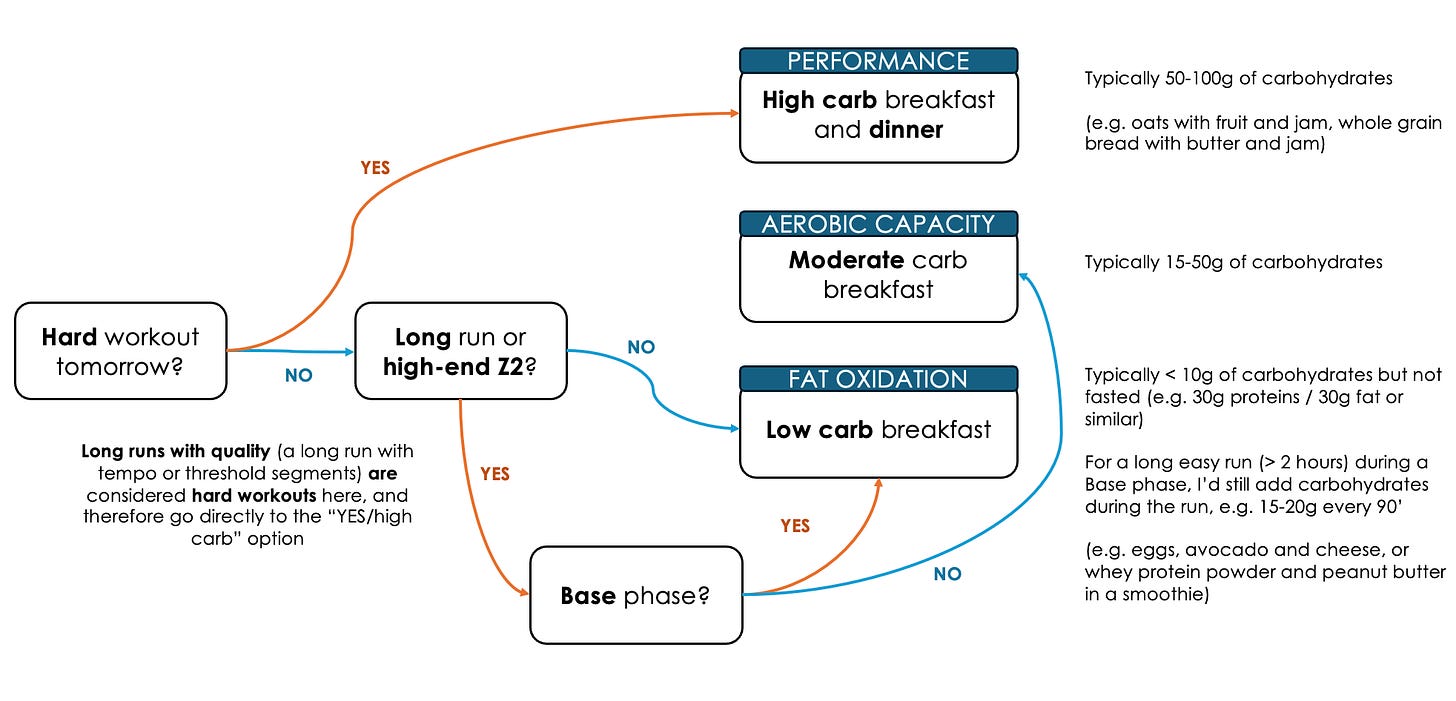

Practically speaking, on most weeks in the past three months, I operated in this way:

Which resulted in weeks structured as follows: H H L L L M L

Where high = high carb, L = low carb, M = medium carb. The example week above includes a high-carb day (e.g. Monday evening), the day before a Tuesday workout, in which I would also have a high-carb breakfast. Then a few days of lower carb intake, as training demands would be different (e.g., easy running, or a few strides and hill sprints), then a moderate carb day for a longer run on Saturday, and a lower carb day again on Sunday. I normally plan meals around protein, and then add lower or higher amounts of carbs depending on the demands of training. Again, if you are new to this, see here.

This approach works very well for me in terms of fat oxidation, as shown above, but I also find that with periodized nutrition, it is easy to stay stable in body composition, and I perform much better in long-distance training sessions or races (as I did at the 50 km di Romagna). Considering that nothing is really off the table in terms of types of food, but I am simply adjusting macros day-by-day depending on training demands, I also find it easy mentally.

The Extra (specificity, heat)

Specificity

This (+ next month) is the last block before Passatore, and as such, training is quite specific, with lots of hills and a higher amount of Zone 2 or high-end aerobic training, near my LT1, together with more tempo/marathon-pace sessions. We can also see this in the graphs below, where we have the typical pyramidal intensity distribution of specific training when it comes to the last few months before marathons or ultra-marathons:

For the 50 km di Romagna in particular, which is a very “muscular” race, with lots of short steep hills, I often trained on similar roads, or even on the race course itself, as it’s just around the corner from Brisighella. As muscular endurance is a weakness for me, this type of specific training is essential to limit the damage on race day.

To complement the low-intensity volume, I have also done more workouts on the hills this year, with a limited amount of hard downhills (probably 2 or 3 sessions tops, over the past two months), and quite a few hard climbs (10 to 25 minutes at VO2max or threshold). Again: specificity.

Heat, strength, and cross-training

I have not done any cross-training during these past months (no cycling, and limited my strength routine to core work, and sometimes glutes and calves). For cycling, I need the weather to cooperate, and it wasn't the case. For strength, I find that during base training, it can complement my running training well, but during big volume weeks and when there is more specificity, the two do not work well together for me. I simply do not have the freshness to do strength training well, and therefore, I focus on running for this phase.

What I used a lot was heat training. At Passatore, it can be boiling at the start, and I am (was?) terrible in the heat. It’s now more than 2 years since I started regular (passive) heat training, and have even mounted a bathtub at home basically only for this purpose. I came to love it now and often look forward to my 25 minutes in 41- 42C:

Passive heat acclimation can lead to improvements even when racing in temperate conditions, but it is particularly effective for spring or early summer races, as we do not have the opportunity to adapt to changes in environmental temperature. At the 50 km di Romagna, we got lucky with the weather, but we did have a few moments of warmer temperatures, which I felt I could handle really well.

All stress matters, and this stimulus also needs to be weighed in the bigger picture of our days and other stressors, but for me, I find that it’s mostly only gains at this point.

The Race

The 50 km di Romagna is a beautiful, hilly course, in the Italian countryside near where we live for part of the year. It’s a bit of a must for people preparing for the 100 km del Passatore, given the similar characteristics of the course in terms of climbs and descents. I do find this course harder than Passatore, as it is full of short, steep climbs, unlike Passatore, which has smoother, longer climbs.

Overall, my race went really well. I raced a 10-minute personal best for this course (and a 7-minute personal best for the 50 km distance, when including flat races). This was the day I had been waiting for a long time. It all came together on race day, the training, the nutrition, the progress, and I’m elated to have raced hard and well and have finally finished an ultra feeling like I raced near my limit, and not only went out to save my legs and be happy with the usual underperformance (with respect to what I can do in shorter distances).

Below, I look at tapering, pacing, and race nutrition.

Tapering

I included tapering here as it is very race-specific.

In particular, my taper is often atypical, as I found that I perform much better right after big training blocks or training weeks, typically pushing what I can do to its limit, and then taking a few days of very minimal training to get fresh from a muscular point of view (e.g. 4 days of 30-45 minutes of training after a week with 20 hours of training). I ran most, if not all, of my personal bests using this approach, including this one at the 50 km di Romagna:

Obviously, there is no point pushing a huge week of training if I’m not feeling at my best. The two things go together: I feel very good, I train hard and high volume, then I rest for the time needed for muscular freshness to return, and I’m ready to race. I don’t do better with the typical textbook three-week taper.

If I’m not feeling it for the big week of training, something is off, and racing is unlikely to go well just because I’m tapering more, hence the pattern: feeling good → big volume → mini-taper for freshness → racing a personal best.

In terms of nutrition, I maintained my low-carb days up to Wednesday at lunch, then I had plenty of carbohydrates from that moment to race morning (Friday). When testing the robustness of my diet in the lab, I could get enough confidence that an acute increase in carbohydrates would not compromise much my fat oxidation, hence I have no concerns in loading on carbohydrates before a big, important event, as long as I have been on my periodized diet in the previous weeks.

In an image:

Pacing

I paced the race by perceived effort but keeping an eye on heart rate as a high-end Z2 cap, i.e., making sure I wasn’t going too much into “unsustainable intensity territory”, for this distance. A cap works in a simple way: if perceived effort says I’m going at the right intensity (i.e. it feels like a moderate effort and I’m still relatively relaxed, as this is a long race), and heart rate is lower than the cap, nothing to worry about (key point here: perceived effort decides, not a target heart rate; if my heart rate is lower than the cap, it can be for a number of reasons, and that’s fine, pushing harder would likely be an error). If, however, I hit the cap (i.e. heart rate goes above 150-152 for a while), and I’m not climbing up, then I make sure to get in better tune with the effort, and slow down a bit. It took a while to get to using perceived effort effectively, and heart rate has been a valuable tool in the process, especially for events that last more than 2-3 hours.

We can see heart rate was rather constant, with a larger decrease on a long descent, where I tried to take it easy not to compromise the rest of my race with fried quads:

Pacing (we had a slight tailwind on the way out and a slight headwind on the way back):

And grade-adjusted/normalized pace, where we can see I pushed a bit harder on some climbs and went a bit easier on the long descent:

Happy with the pacing overall, something that comes down to “finding the right intensity”, and also to metabolic flexibility and nutrition, which I discuss below.

(in race) Nutrition

Here we are, the trigger topic.

While it seems that most reasonable people can get behind periodized nutrition as a way to adjust day-to-day nutrition according to training demands (I mean, it’s pretty basic and obvious after all), the idea that in 2025 I am not eating 100s of grams of carbs per hour during a race is really maddening to some.

You’ve got to do it. You cannot possibly perform well without doing it, even if it’s likely that your body is not using them. Or can we?

Please breathe deeply before you read what follows.

Given what I had learned about my body’s recently developed ability to use plenty of fat as fuel even at race pace (see image above), I figured the best way to move forward (for me!) was to maintain a steady intake of carbohydrates (blood glucose does matter and you don’t want to experience dips during a race) that would however lead to no gastrointestinal issues (GI), nausea or else (a common problem, for me!).

Since my metabolic flexibility has improved, I often see that I can train for much longer, even during hard, long workouts (marathon pace/tempo), with minimal fuel and fatigue. The goal is not to minimize fuel, but to feel good and to perform well. If I am prone to GI issues, nausea, and what else, I will try to see if I can have fewer, not more, carbohydrates, and rely on my body’s ability to spare a lot more glycogen these days. Doing the math for a marathon tells me I burn so much fat at high intensities now that I could race a personal best without any gels (please understand that this is theoretical, as I said above there are reasons why carbohydrate intake is key even if we have enough glycogen to keep going for the entire distance, e.g. blood glucose stability and central effects - but very little is needed for these effects, e.g. 10-15 g/hour). Doing the math for a 100 km race tells me I can go on for 9 hours with less than 20 grams per hour (see this section for the details). While for the 100 km I will need to be methodical, for the 50 km di Romagna I really had zero concerns about my in-race fueling, as I saw in training I could go on for ~30 km at marathon pace with 10 grams of carbs per hour, and feel fine at the end. (please note that I did this because I love to experiment in training, and I wanted to see what was possible; I did not do this because I thought it was “the best way to race”).

Eventually, I decided to go by feel and have no gels before the start, then a gel anywhere between 7 and 9 km, and then take that as the approximate race frequency. After the first gel at 9 km, I had one at 20 km, then planned to have another one at 27, due to the course (I wanted to have it before the descent), but the following time I looked at my watch thinking about nutrition, I was at 32 km and feeling great. I did take the gel, and eventually took another 2, for a total of 5 SIS gels (given my reduced requirements, I now went for glucose-only gels, in yet another attempt to minimize my frequent GI issues).

This makes for 22g x 5 = 110g of carbohydrates in 3 hours and 47 minutes.

What I did remember to take regularly was caffeine, 100 mg after 1/3rd of the race, and another 100mg at 2/3rds of the race.

The outcome?

No cramps, no nausea, no GI issues, no fatigue, no walls, a strong finish, and a personal best.

Should you do the same?

Of course not, you are not me. This is about individualization, and this is what I needed, but it is not a magic formula that works for all (see last section).

Takeaways

To conclude this blog, I would like to cover two more aspects of this whole journey: the performance breakthroughs I made in my own training, and how important it was to understand my limiters and truly individualize my training and nutrition, as opposed to following whatever was hip at a given point in time.

Breakthroughs

This year, when I thought I was done making big jumps in performance, nutrition gave me a new breakthrough for the events I care about the most these days (i.e., the ones longer than a marathon).

As a short summary, here is how I got better in the past 15 years (some of it, covered here):

2009-2011: Just run, basic adaptation to a new sport

First half marathon in 2h 08’, then in the 1h 40’-45’ range for a few years

2016-2017: Training intensity management (leading to higher volume)

Half marathon down to 1h 24, first marathons (~3h 20’)

2022-2023: Specificity and training for the demands of the race

Half marathon down to 1h 20’, first sub-3 marathons

2024-2025: Metabolic flexibility for ultramarathons

Large performance improvement in long races

Progress is all about individualization

I haven’t told you the stories above about nutrition, tapering or else, because I think that’s what’s best for everyone or because I think you should do the same.

Quite the contrary.

I stress those stories because they are all about individualization. They are all about understanding that different things work for different people, and that’s what training (and coaching!) is about.

Sure, we start from evidence-based practices, but we need to experiment and try things and figure out what brings the best out of each individual, and I can guarantee you that’s not a three-week taper or 120g of carbs/hour. For some, it will be, for others, it could be a big week of training just before an important race, and then enough carbs to limit dips in blood sugar.

Let me tell you another story.

For decades, I suffered from cramps. I could never do a long run with intensity (e.g., tempo or marathon pace) without cramping. I ran all my “fast” marathons while managing cramps for 10-15 km, hurting and slowing down, despite already starting with underwhelming goals given my times for shorter distances (e.g., going for sub-3 despite running 1h 20’ for the half). All the experts told me to have more carbs to solve the problem.

What I needed was fewer carbs. Not in training or racing, but fewer carbs in my daily diet. I needed to completely change my metabolism and improve its flexibility and ability to burn fat. Yesterday, I ran 50 km of hills faster than I ever could, without any cramp. I ran the last kilometer faster than any previous kilometer, to catch a friend just 50 meters from the finish line (sorry, Mattia). I could never do that before changing my nutrition, and I could do it yesterday while eating very few carbs during the race.

I start from the science, but also appreciate individual variability, experiment, and eventually stick to what works for an individual consistently, until it doesn’t. Then we take a step back, re-think, and see what we can do. Can you get behind this approach?

Happy training and happy racing!

How to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

As a HRV4Training user, the best way to help is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you for supporting my work.

Endurance Coaching

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and fill in the athlete intake form, here.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching. He is a certified ultrarunning coach.

Marco has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, Endurance Coach at Destination Unknown, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine.

Social:

Hey Marco, nice post, thanks for sharing. Are you wearing a polar verity sense? If so can this be used to measure morning HRV on HRV4TRAINING? I find the H10 a bit cumbersome :)

What a great post Marco. Mindful about everything you do. We are all individuals, but you are running “experiments” of a sort. Essentially “I predict this or that will work”, then monitor everything possible to assess whether its an accurate prediction or a prediction error.

You mentioned the in-race gut problems, and am curious about whether you have ever tried taking L citrulline?

Have you noticed any intensity related differences?

There are a number of people in my circle who always have difficulties (albeit in races where prolonged high-intensity surges are a given). All have had semi-miraculous improvements with L Citrulline. I’ll try and track down the references that led me to run the experiment on myself.