4 things I'm changing and 4 things I'm not changing while preparing for this year's 100 km del Passatore

Cross-training, heat acclimation, racing, fueling, and more

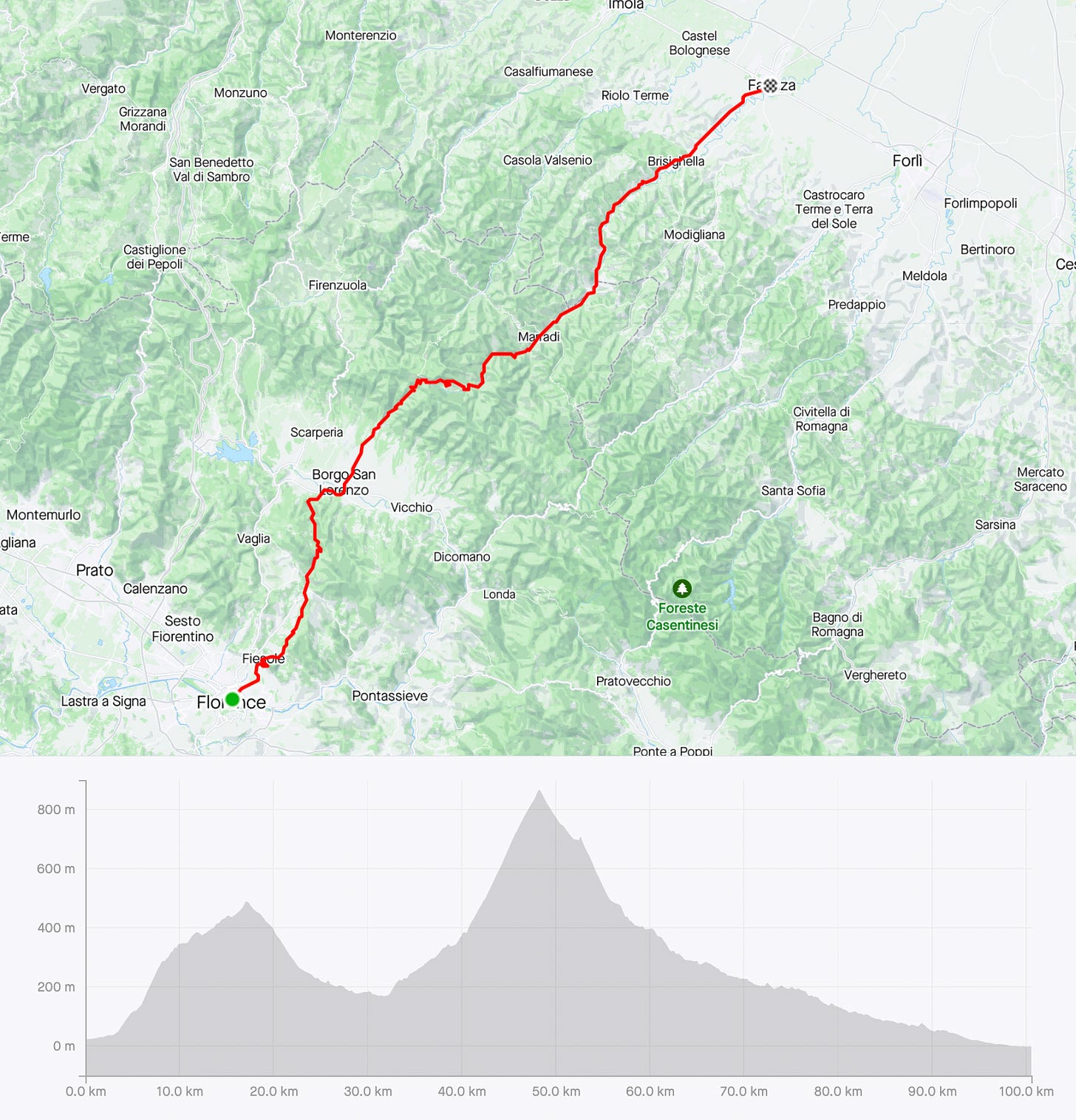

The 100 km del Passatore is the oldest ultramarathon in Italy, which goes from Florence to Faenza (passing from Brisighella, where I recently relocated).

I am drawn to this race mostly because of my personal history. I have lived not far from the finish line for 25 years, before emigrating to the Netherlands first and the States later. My father ran it 47 years ago, it was the second edition. As a child, I used to go with him to see his friends competing for a top-10 finish. I have many memories of evenings and nights spent between Marradi and Faenza, supporting runners battling this somewhat crazy challenge. If you were born here, you know the race. The heat, the hills, the 100 km. It’s special.

As my love for the sport kept growing over the years, I finally signed up and decided to give it a go two years ago. Eventually, I had a rough day in the heat and ended up in a hospital with massive cramps (DNF). This forced break triggered some self-reflection and renewed interest in trying to get back into a different type of training and shape, as well as to address a few things differently, as I made some novice mistakes back then. Last year, I trained very well and got as fit as I could possibly be. I ran personal bests on every distance from the 5 km to the marathon, but Passatore was canceled due to major floods and landslides that hit our region just two weeks before the race.

Eventually, I did find another race two weeks later and ran a good 100 km in the night in Switzerland at the Bieler Lauftage (race report here), but you know, it is not the same thing.

So here we are again, two months to the next 100 km del Passatore.

As I spend much of my time either training or thinking about training, here are a few things I’ve changed, and a few things I have not changed, for this year’s race.

I hope there is something useful in there for you too, and please feel free to comment below and share your experience. This is how we learn.

What I’m changing:

cross-training

additional intensity using hills

active heat acclimation, with a twist

no racing

What I’m not changing:

fitness first

passive heat acclimation

race simulations

fueling

Let’s get to it then.

What I’m changing

1. Cross training

I had never cross-trained consistently until last summer, when a running injury and lots of motivation to maintain fitness for an October marathon, made me start cycling 25 hours per week.

While it's difficult to evaluate most training interventions we try on ourselves (you can never really know what the outcome would have been with / without the intervention), the results of this experiment surprised me quite a bit. I ran a 2h 56’ marathon (a personal best) while running less (full report here).

We know from the scientific literature that intensity on the bike can transfer to running. This is maybe easier to understand as central changes (e.g. in VO2max) can be developed or maintained with different types of workouts and sports. On the other hand, cycling volume can probably help in different ways too (e.g. as an additional aerobic stimulus, but also mentally, when you stay out many hours). Obviously, we still need to run, as the muscles used differ, and running economy might take a hit if we don’t run enough.

The main issue with runners is that we cycle only when injured. However, I think there are great opportunities in using cross-training, and in particular cycling, to make gains as runners. The key though is not to replace running with cycling, but to add cycling to running, so that we can safely train for more hours, and even accumulate more time at high intensity.

This year I am cross-training more, aiming for at least 6 hours of cycling per week, with one high-intensity session every 10-14 days. This is on top of a high volume of running, which brings total training time in the 20-25 hours / week range. Plus, I can ride the course of Passatore any time I want, just to keep the obsession going. How cool is that.

I do not run every day, as I find that the risk of breaking down is just too high for me. The day after a really hard session (e.g. 25-30 km at marathon pace), I could go out running for 30-45 pathetic minutes, with everything hurting, or I can go out for 4-5 hours on the bike, without issues. It’s an easy call. Give the bike a chance.

See also:

2. Additional intensity using hills

Intensity makes me a better runner. Most likely, it makes you a better runner too. However, intensity breaks me routinely.

This year, I am trying something different, to accumulate more time at higher intensity, while minimizing injury risk. On top of cycling, I am also adding moderate or hard hills. I have moved to Brisighella for a few reasons, one is certainly the hills around me, a perfect training environment for both running and cycling.

Pushing uphill gives me a great cardiorespiratory stimulus and none of the muscle soreness. I have tried this a few times, during long runs (e.g. 45 km with 4 big climbs @ 6-8% grade at moderate intensity) or shorter ones (e.g. 8-10 minutes all out @ 8-9% grade). I was quite surprised to be able to do workouts on (semi) flat roads the following day with no issue. The same applies to the bike, after pushing hills as hard as I could, I had no issues running 30 km at marathon pace on the following day.

To be clear, I am one of those people that can barely do a hard session every week. I am always sore. I break down easily. I am really weak from a muscular point of view. However, changing the training modality (bike vs run) and using hills allows me to run harder more frequently.

No need to overdo it, but it is easier this way to make sure I am consistent with quality, not only quantity, of training.

See also:

3. Active heat acclimation, with a twist

I’m a big fan of passive heat acclimation (see later). I’ve used it a few times and the results have always been good.

However, this year, I am adding active heat acclimation too, but on the bike. Last summer, somewhat randomly, we had the only warm week of the year in The Netherlands just before (and including the day of) a 50 km I had signed up for. It was during my “cycling as much as possible” phase, and for practical reasons, I used to run in the morning, and cycle in the late afternoon.

Despite not being any good in the heat, I had a good race at the 50 km in WInschoten, and finished 4th overall. People were dropping in front of me for the whole race (I think I didn’t actually pass anyone, they just all quit one by one). How did that happen? While unplanned, I had been riding a lot in the heat in the afternoons, while doing my quality runs in the morning. I think this is a strategy I can use combined with passive heat acclimation, for Passatore.

As the days get hotter, I can keep doing quality training in the morning (running), and add some hours of cycling in the afternoon (when hot), even at low intensity. This will give me benefits that will also transfer to running, without really stressing me (low cardiorespiratory demand and also no stress on 'running muscles').

Obviously, the weather plays a role for this one, but considering that it’s 2 months to the race and already 25 C this weekend, it seems like there will be plenty of opportunities for using active heat acclimation on the bike.

See also:

4. No racing

Last year I raced a lot. I needed it, and in fact it was one of the things I had changed from the previous year. I needed to get used to it, to feel less stressed and more in control, and to gain confidence. It might sound silly to have these problems at my level (i.e. average), but what can I say, racing used to get to me in dysfunctional ways. I was really stressed.

Before the Ravenna marathon, the first time I had a shot at running ~3 hours, I slept maybe an hour or two. Before Manchester, the second shot, I slept maybe 4 hours. Before Amsterdam, I slept like a baby. The same before the Barcelona half marathon last month. Racing worked. Now I don’t need racing.

Don’t get me wrong, I love a race here and there. Great energy. However, I dig deep and it can take a long time to get back to normal or I can get injured (racing a parkrun in July 2023 brought me issues that I still had in February 2024). At this point in my journey, I understand my limits better and I prefer to focus on training. After the Barcelona half marathon, it took me 4 days to be able to run again, and 3 weeks to be able to do any intensity. It is just not worth it.

Last year I qualified for Boston, and I will be running it next month, but I will take it easy and run in ~zone 2, as a good training stimulus that doesn’t require much recovery.

Full focus on Passatore.

See also:

What I’m not changing

1. Fitness first

During my first preparation for Passatore two years ago, I was obsessed with volume. Probably a naive mistake of first-timers at such a long distance. I ran very consistently, 6 days per week, 130-140 km per week, for many months. However, I was also getting slower and slower, accumulating niggles, and being unable to do proper workouts.

Last year, I still wanted to keep up a decent volume, as I know I benefit from it, but without sacrificing the intensity. It was clear at this point that just running more easy miles wasn’t working for me, and that more isn’t always better (a hard concept to get behind at times). In other words:

Fitness before volume.

Both volume and intensity matter, but I find it easier to accumulate volume (you just have to run after all), while intensity requires adequate health, planning, recovery, etc. - and is the first thing to go when we have a setback. I tried to make sure I wasn’t slipping this time.

My periodization has changed in an attempt to prevent physical issues while allowing me to train properly, and while it is even more conservative now, intensity remains key.

See also:

2. Passive heat acclimation

The main unknown for Passatore is the heat. As the race is the last weekend of May, it is not necessarily crazy hot. In fact, two years ago when I raced it was one of the hottest race days in the past 15 editions, and I am secretly hoping we’ll get a good day this time.

However, it is key to get to race day ready for a hot day. Two years ago I opted for training in the heat (i.e. active strategy). Training in the heat meant that I had to limit a lot what I could do and that I eventually trained poorly over the last 2-3 weeks before the race when the weather got warmer. Additionally, as the race is during a period in which days are getting warmer and warmer, training in the heat means you are always trying to catch up with changes in temperature, which is not ideal.

Last year, I opted for a passive strategy: the hot tub. The science on the topic is quite fascinating (check out Jason Koop’s book and podcast for a lot of great resources about the topic). Long story short, sauna or hot baths can give you the same benefit you get from training in the heat, without messing with your training as much.

I have used a simple protocol similar to what Jason covers in his material, which includes 2 weeks farther away from the event, 5 days per week, 20 minutes at 40 C, and another week closer to the event. Last year I found myself able to run at a low heart rate on very warm days, which was certainly unlike me. This year, I also used the same strategy in preparation for the Barcelona half marathon, which wasn’t hot, with the idea that passive heat acclimation can improve performance even in temperate conditions (just like altitude).

As I mentioned also above for cross-training, it is impossible to know what time I would have raced without the heat protocol, but I did race a personal best despite training suboptimally due to many physical issues.

Passive heat acclimation stays.

3. Race simulations

Race simulations are the real deal. Last year I learned lots while doing them (and making mistakes), which eventually allowed me to race well when the race came. Maybe there is less need for them right now, as I feel like many aspects are really dialed down (e.g. fueling, hydration, clothing, pacing, and all the things I got wrong before), but I think they are still worth the time and effort required for a number of reasons.

In an ultra, basic physical fitness is necessary but not sufficient. In particular, I know that if I go out for 40-50 km I do not face any of the challenges that can get me in trouble on race day. I need to go quite a bit longer to put myself in a situation in which the following can happen: fueling is insufficient after 5-6 hours, or eating the same food for so long gets me nauseous, or I get a niggle somewhere and I need to work through it, or I cramp badly on a long downhill after running 5 hours and I need to also work through it, or I have issues with hydration, etc. - I need this very long day to challenge myself to the point that is not quite the race, but at the same time, is not as predictable as regular, shorter, training (and yes, 50-60 km is just not enough).

As a rather anxious and insecure person, this is also necessary mentally, to gain confidence that I can actually finish the race and I am fit and ready. Despite my love for distance, my limiters don’t go well with it (inefficiency, cramps, etc.), and a bit of practice can be helpful.

The first race simulation will be this Saturday, as the temperatures will rise quite a bit, I figured it would be a good chance to get uncomfortable and see how I deal with it. I’m aiming for about 70 km with elevation gain similar to the race.

Let’s go.

4. Fueling

Running an ultramarathon is dramatically different from running short distances or even a marathon. Two years ago I read as much as I could, and fortunately, I had Daniel to help me out as well. However, I still struggled to find the right setup, what to eat, how frequently, etc. - I think this just comes down to experimenting a lot, and maybe I didn’t experiment enough before. Last year, I thought I had figured it out, until the heat came. During a race simulation, I had all sorts of issues with the setup I thought was the one I was going to use for the race. As the temperature rises, blood gets diverted to the skin for cooling, and both your digestive system and muscles will pay the price. Managing intensity becomes even more important, but the type of food we eat does too.

Since then, I have used always the same strategy for marathons and ultras, and it went well when racing hard (e.g. a marathon personal best), racing in the heat (e.g. at the Winschoten 50 km), or racing long (e.g. the Biel 100 km).

What works for me is simply to just use gels, as I cannot take any solid food unless I run quite a bit slower than what I want to race. I have a gel every 6 km, which is every 25 minutes in a marathon and every ~33 minutes in a 100 km (25-30 grams of carbs per gel). I also take a sodium pill more or less at the same frequency (I lose lots). I then drink at thirst based on what’s available on the course or what I carry. More frequent intake gives me GI distress, and while this amount might be on the lower end of the spectrum with respect to current trends, I am always for a minimum effective dose first (throwing up or not digesting food because I’m having too much won’t do me any good).

Since I’ve started to be more methodical, I have experienced fewer lows, and I often finish very long runs without being particularly hungry or tired, which never happened before. I was also fortunate to have a good chat with Aitor during a run in Barcelona. Aitor is a great expert on the topic and did lots of interesting work showing how muscular damage is reduced when carbs intake is higher (paper here), another reason why I try to eat more during my training runs these days, especially when out for many hours as it happens when preparing a ultra.

That’s a wrap for today.

Please feel free to comment and provide your input/view, always happy to challenge these assumptions and talk training.

You can follow my training journey on Strava, here.

Thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Twitter: @altini_marco.

Personal Substack.

Thanks for the article. Very interesting. I've just had a quick scan and will take time to read it through properly including links shared. One question in my mind is how long term HRV measurements would help training from being a marathonian to doing ultra such as 100k (flat or hill running). We often see 100k training plans over several months but life is never a straight line so I see HRV being a tool that would help me adjusting the plan and see how the body react (to complement RPE and hear rate stats for each run).

bravo bell'articolo, completo ed esaustivo!

Mi piace il setup da vero esperto dei dati su cosa mantenere e cosa sperimentare di nuovo.

Ti seguo su Strava e lo faro' di piu' su substack!