[TrainingTalk] Experimenting with Periodized Nutrition for Endurance Performance

Fueling for the work required, periodizing carb intake, fat oxidation and more

I started “a little” experiment last month, changing my diet to a periodized nutrition approach, with two goals in mind:

Improve body composition (limited to an initial phase that will last maybe 2 months or a little longer).

Improve fat oxidation

Both goals are to be considered as means to an end, i.e. improving endurance performance in long events (8-10 hours).

In this blog, I discuss substrate utilization and periodized nutrition and how this fits with my individual physiology and limiters.

Personal Background

In mid-2022, after a disappointing DNF at Passatore, I started turning around my performance, with an initial focus on improving body composition. As it sometimes happens, after a while, I got overly focused on weight, in unproductive ways. One year ago, I finally changed my approach. After struggling a bit with low energy levels, I let performance decide, ate more, gained some weight, and eventually raced personal bests (see my training and race reports for the Barcelona half and 100 km del Passatore, where I also touch on this aspect).

Why am I doing this again then, you might ask.

It comes down to both my performance and my health:

Over the past 6-8 months I have underperformed. I have trained lots but have mostly regressed in my running performance, which is still something I care about and would like to improve a little more, even if my genetic ceiling is rather close by now.

In terms of my health, I have experienced gastrointestinal problems also outside of training, both in summer and in autumn, for several weeks. On top of this, it’s very easy for me to gain weight (both muscle and fat), and I think I just let my diet slip too much, getting into a pattern of “it’s fine because I train a lot”, somewhat typical of recreational endurance athletes (relocating to Italy for part of the year didn’t help!) - eventually I got back where I had started 2 years earlier.

A good time to challenge my beliefs once again, and implement some changes.

Periodized Nutrition, Low(er)-carb diets, Fat Oxidation, and (ultra) Endurance Performance

Our muscles use two primary fuel sources during exercise: carbohydrates and fats. Carbohydrates provide quick energy but are stored in limited quantities as glycogen in the muscles and liver. Fats, on the other hand, are a nearly limitless fuel source but require more oxygen to convert into usable energy. The proportion of fat and carbohydrate burned depends on factors like exercise intensity, duration, and our diet. At lower intensities, fat oxidation predominates, while carbohydrates take over as intensity rises.

Why do we care about fat oxidation?

As covered in a recent review by Ed Maunder and co-authors (paper here), the reasoning is that greater reliance on fat oxidation for energy during prolonged efforts reduces the need for endogenous carbohydrate use (which is a limited resource). This, in turn, can delay the onset of fatigue as well as allow us to eat less during a race, with associated benefits (e.g. reduced gastrointestinal problems). For ultra-endurance athletes, who already spend most of their racing time at relatively low intensities, higher fat oxidation could make a large difference.

How do we improve fat oxidation?

Studies highlight the potential of low-carb diets for enhancing fat oxidation, which can be advantageous during prolonged exercise where carbohydrate availability becomes a limiter. Keep in mind that this does not mean that you have to go into a keto diet or even a daily low-carb regimen, but it means that we can use a periodized nutrition approach, in which carbs are restricted strategically a few days per week (typically before low intensity or shorter training sessions) to improve fat oxidation and we could call metabolic flexibility.

Given my physiological profile and limiters, i.e. inefficiency, high energy expenditure, and poor running economy, improvements in fat oxidation and efficiency could have additional benefits over ultra-distances. As my VO2max is already “high” (it goes together with the high energy expenditure from which my poor running economy also results), I think in my specific case there is more to gain than to lose, at this point.

Let’s Look at Some Data

I have had a high-carb diet for the 40+ years that I have been on this planet, and unsurprisingly, it shows.

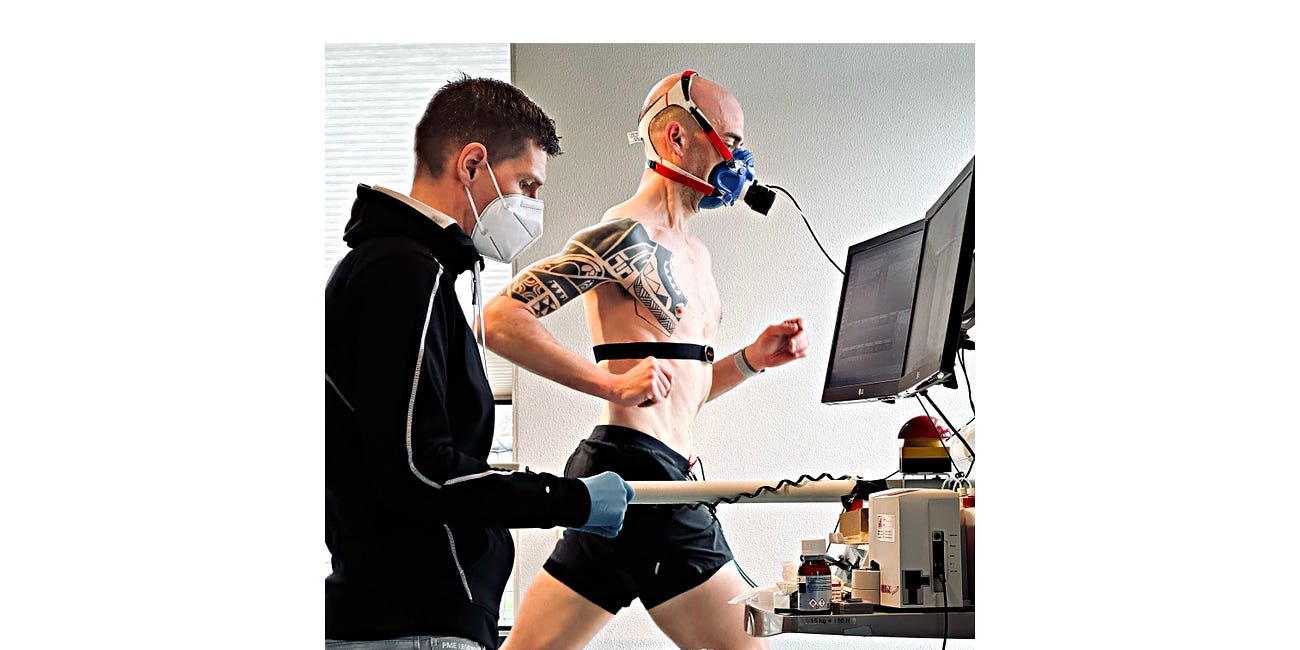

When looking at data collected with indirect calorimetry over 11 years, I can see dramatic changes in my physiology due to endurance training:

Maximal aerobic capacity, or VO2max, moving from the low 50s to 62 ml/min/kg.

The cost of running, or running economy, similarly improving dramatically, despite being a negative outlier (see image below).

And yet, when looking at my fat oxidation rate in the best shape of my life, it’s very low even at intensities lower than what I can run for 100 kilometers:

The data above is quite revealing. Looking at most data I have collected shows clear changes in the right direction over a time period of a decade (as also shown by large changes in performance). However, there is absolutely no sign of improvement in fat oxidation (keep in mind that fat oxidation changes greatly also based on what we eat before testing, but if I always eat carbs, that’s what I get also when I train or race).

Eventually, we burn what we eat. And I (used to) eat lots of carbs.

Getting Practical with Fat Oxidation

How do we change the graph above, i.e. how do we increase fat oxidation?

Typically, either by training more at low intensity or by changing diet. Considering that I spend months moving slowly for 15-25 hours/week, I doubt the answer in my case involves more low-intensity training.

Hence diet it is.

As covered above, the approach I’m testing isn’t a ketogenic diet or even a daily low-carb regimen, I am not doing anything extreme nor I am removing any foods from my diet. The quantities change, to make it a periodized nutrition strategy in which on a day-by-day and meal-by-meal basis carbohydrates might be restricted (especially in the first phase in which I am also working on body composition and as a result losing weight), but I still eat carbs (it would be culturally inappropriate to do otherwise!).

This is important because while research highlights how a low-carb diet can improve fat oxidation, it can also impair performance at higher intensities.

In practical terms, periodizing carbohydrate intake around training intensity and duration can mitigate the downsides, allowing athletes to benefit from both metabolic adaptations and adequate glycogen availability when needed: this is the approach I am trying.

Periodized Nutrition

Periodized nutrition simply involves modulating carbohydrate intake based on training phases and workout intensity. It seems obvious that the fuel we use should change depending on the demands of our training, but this is an often overlooked aspect.

Currently, I have structured my intake as follows at the macro level (see how I define Training Phases here):

Base Phase: Lowest carbohydrate intake to promote fat adaptation. At the moment I am in a weight loss phase, hence with a small daily caloric deficit, but regardless, this would be the phase in which training is more sustainable with fewer carbs overall, even though everything is still modulated on a day-by-day and meal-by-meal basis, with high carb intake before workouts.

Support Phase: Moderate carbohydrate intake to support increasing training intensity for extended periods.

Specific Phase: Higher carbohydrate intake to fuel race-pace efforts and optimize glycogen stores. This is the training phase in which I typically train the most (up to 200 km/week).

While carb intake will increase over different training phases, the idea is still to maintain it rather low with respect to my “historical normal”, and therefore I plan to still “train low” for 2-4 days per week across all training phases.

Finally, below is how I modulate carb intake at the microcycle level (see here for Training Types):

Easy, Endurance, Neuromuscular, Doubles: low-carb breakfast and lower-carb intake during the day to enhance fat oxidation.

Tempo, Threshold, VO2max: high-carb breakfast and slightly higher intake the previous evening and after training to make sure I can execute the training properly.

During long easy runs (e.g. on trails, including plenty of walking/hiking), I am currently eating, but less than I used to. Obviously, it’s an iterative process, especially in the first weeks, in terms of balancing macronutrients.

Wrap-up

I am often guilty of ignoring diet and focusing only on the training side of things, hoping “more training will fix it”. This typically results in disconnecting from my body, e.g. eating mindlessly, and not listening to the right cues. Regardless of macronutrient content, I think that the simple act of “focusing on something” can often lead to progress as we indulge less in what we already know are suboptimal behaviors.

My main goal at the moment is to optimize my nutrition for better performance in long ultras, particularly in hot conditions, where gastrointestinal issues have been a recurring problem.

Given 1) the potential of periodized nutrition and low(er) carb intake for enhancing fat oxidation, 2) the possible advantages increased fat oxidation can bring during prolonged exercise, 3) my physiological profile and limitations (i.e. inefficiency, high energy expenditure, poor running economy, non-existent fat oxidation), 4) my goal race (hey, if you’d like to join, registrations are open), which might include hours in the heat, I’m curious to see if switching to a periodized nutrition approach, with lower-carb intake used strategically, can bring any benefits and lead to improved performance.

Can I race better in the next 2-3 years using this approach?

Time will tell.

In the meantime, this is just another opportunity to learn.

Updates on this experiment (including testing data after 8 weeks, actual diet followed, etc.) will follow on my Yearly Training Log here on Substack and on Strava - thank you for following along!

Update: How Did it Go?

Find out, here.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Great article, Marco, look forward to reading of your progress. I think a podcast between yourself and Zac Bitter would be enlightening based on his history of performance utilising the same approach you are.

Hi Marco, this post is so interesting. I am very surprised with this fat oxidation level for a well trained with good volume and good amount of low intensity training. I would have expected better mitochondrial efficiency for fat oxidation with this volume independently of carb loading. The next lab tests will be very useful !

Do you think that measurement of blood ketones (devices seems accurate, cheaper than lactates ones) can give a good estimate of fat oxidation during training ? Did you experienced during previous low intensity training car loaded some symptoms like hypoglycemia, hungry, dizziness at the beggining that disappear with ingestion of carbs ?