Insights from continuous glucose monitoring

health, stress and training

In the past years, I’ve used a few continuous glucose monitors (CGMs). These are sensors that measure your glucose level within interstitial fluid, typically for about 2 weeks. I’ve mostly used sensors from Abbott, via Veri or Supersapiens.

As a scientist working with physiological data, I find our ability to measure our body’s responses quite fascinating, from HRV, to exercise physiology, to glucose levels measured with CGMs. While curiosity has mostly driven my initial experiments, a few aspects have shown repeatedly to be impacted by my behavior, and as such, have led to what I consider useful insights, in terms of health, stress, and training.

Below, I cover briefly these aspects.

Lifestyle: diet and movement

In the past year, I made a few changes to my diet, and also to my behavior in terms of non-training related physical activity.

In short, I’ve been paying a bit more attention to maintaining a healthy diet outside of training and sometimes limiting my caloric intake, without compromising training. I have also made an effort, thanks also to the data I’ve seen from CGMs, to move (typically walk) a lot more during the day. I normally go for walks after every meal (2-3 times per day), on top of training.

I believe these changes have improved my metabolic health, something not to be ignored until it’s too late, which is unfortunately the approach used in medicine. Keep in mind that in medicine, we make up thresholds that determine what is health and what is disease, but obviously, there's a continuum. This is why in my opinion it's odd to hear that a certain device should only be used by diabetics (or now pre-diabetics). Thresholds are a necessary evil, but we need to try to look beyond them, and certain tools, can be helpful.

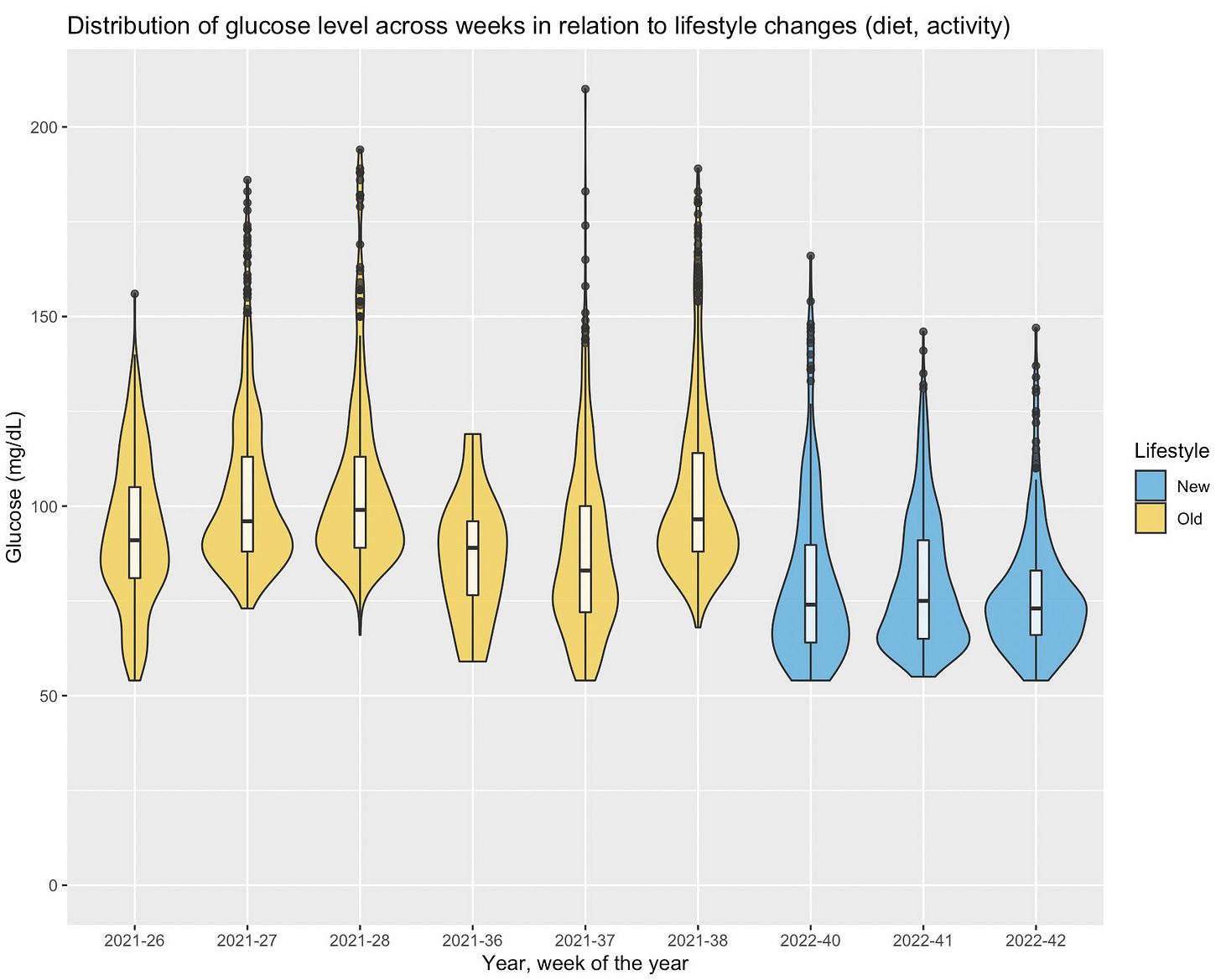

Back to my case study, here is a look at my glucose levels before the past year and during the past year (when I implemented these changes), grouped by week. The average went from 98 to 79 mg/dL, which I consider an improvement in my metabolic health:

In this case, objective feedback has been quite valuable to reinforce good practices that I already knew (e.g. in terms of eating well or moving throughout the day). Data can be helpful that way.

Stress and heart rate variability

As you probably know already if you ended up here, I am quite interested in the body’s response to stress, and in seeing how we can track this response using heart rate variability (HRV).

HRV is our best, non-invasive marker of stress when measured under certain conditions. However, a lot more is happening in the body when we get stressed. In particular, physiologically, we know that high stress is associated acutely and chronically with elevated glucose in the bloodstream and reduced parasympathetic activity.

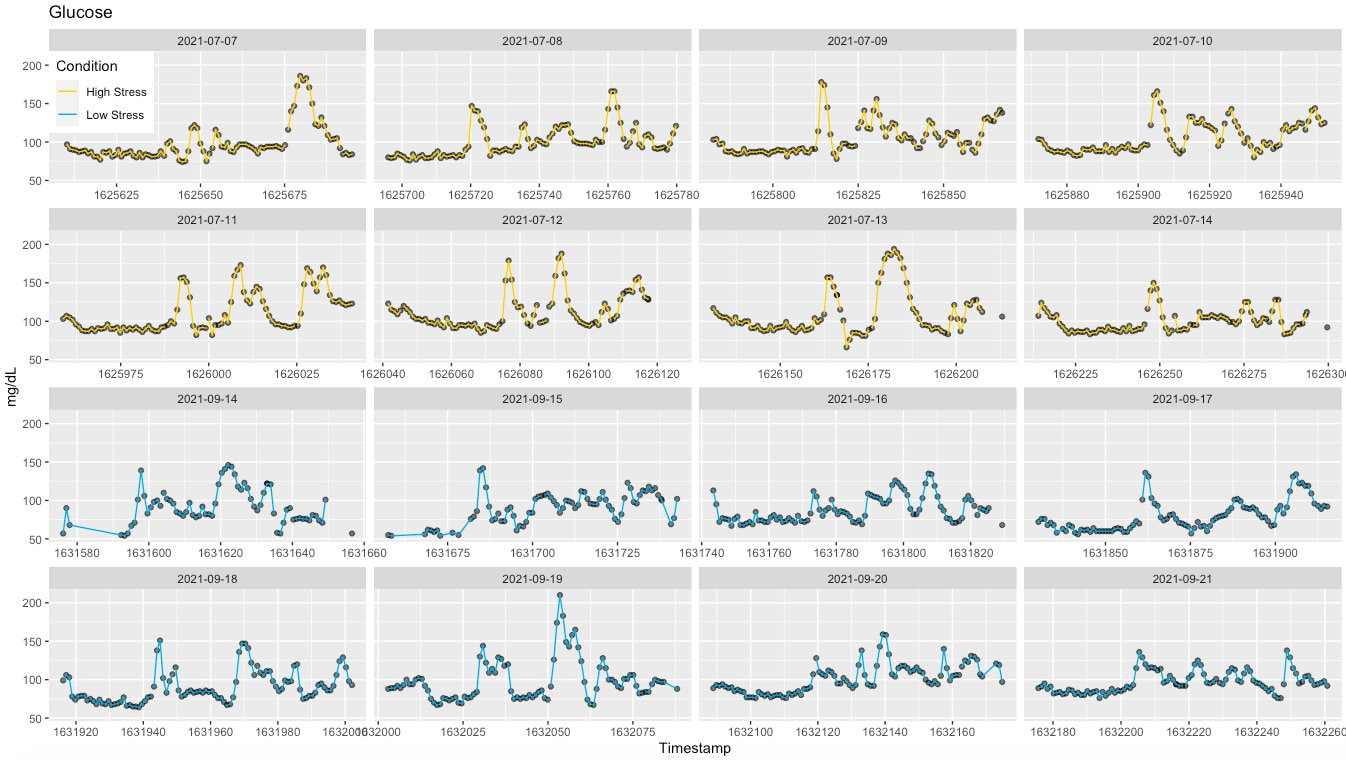

Here is another example of my own data. In July 2021 I had a strong negative stress response (cumulative stressors), resulting in arrhythmia and concerns for my health. I've talked about this before, but here I want to focus on what happened to glucose during that week.

Coincidentally, I was wearing a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) since the previous week and noticed that after meals, my glucose was spiking really high, near 200 mg/dL, consistently:

As usual, I was also monitoring my resting physiology (HRV and HR) using HRV4Training (morning measurements), and saw quite a dip in HRV, as well as a minor change in heart rate. This is the type of stress response I often discuss.

Very interesting to see poor regulation at work so clearly. Note that when measured in the night, HRV did not track at all with what was going on, as shown here, because it was artifacted by the arrhythmia, something wearables ignore - this is one of the many reasons why you should measure your HRV in the morning.

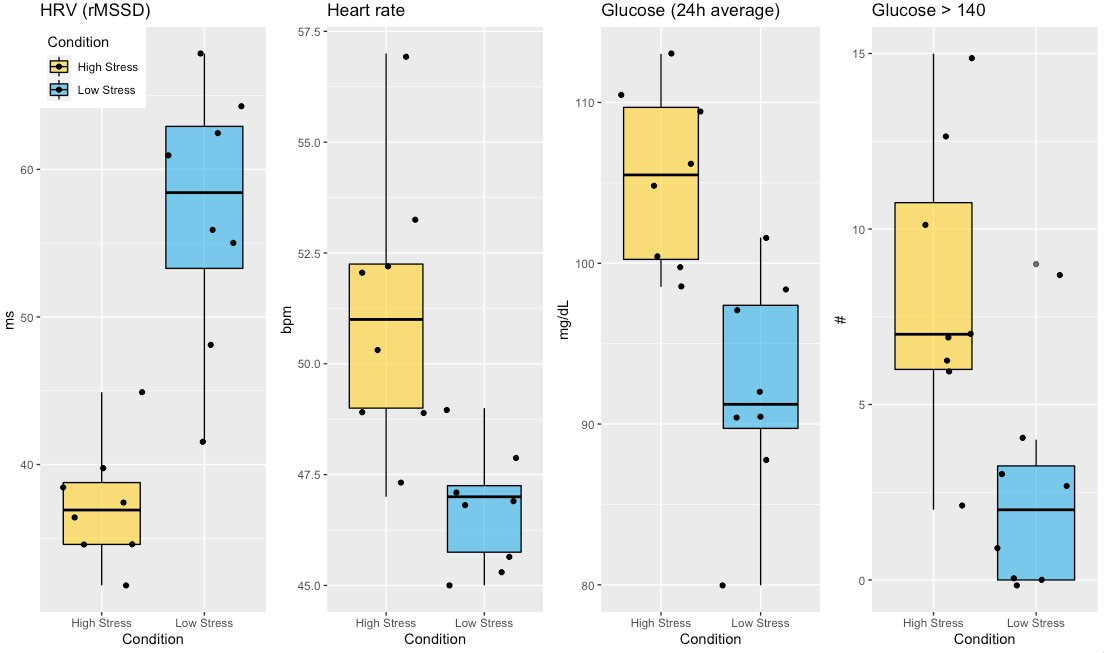

Below I grouped the data between high and low stress conditions, to better highlight differences in resting heart rate, HRV and glucose.

In particular, we have the following:

42% decrease in HRV

9% increase in resting heart rate

13% increase in 24h average glucose

These are all useful signals to better understand stress responses and hopefully get better over time.

Here is a good study combining the previous point with this one, looking at glucose, heart rate variability, and metabolic health.

Training: pre-workout nutrition timing

In terms of training, CGMs can be helpful to better time nutrition before training. This is all very well documented in Supersapiens’ blog, hence I will keep it short here.

Basically, there’s an optimal window for eating before a workout, in order to avoid a dip in blood glucose. In case you exercise regularly, you might have experienced such a dip, and in that case, you already know that it is not fun. You feel very sluggish, weak, maybe with additional headaches or pains, and it can take an hour to get over it and feel normal again. I was quite prone to this dip, but with all that goes on in life, I hadn’t linked it to something as obvious as the timing of food intake before exercise.

Using the data, I now know that I can exercise about 2 hours after eating, or right away, but I should avoid anything in between. This is a slightly different window with respect to what is normally recommended, but don’t forget that everyone is different, and only by tracking our own response, we can better understand what works for us.

I hope this was informative, and thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Until last night I didn't know CGMs existed and hence my visit to your helpful article. As someone with a 'sweet tooth' I'm sure there are improvements and adjustments I can make to improve my wellbeing, training and racing. Is there an entry level CGM worth experimenting with?

If you are having a glucose drop if you don't eat before working out, could it be because the body is not trained to be metabolically flexible. By that I mean being able to switch easily from burning glucose for energy and instead burning fat and using ketones for energy? Just my 2 cents from all my reading from what Peter Atilla, Dave Asprey, and Gundry say from their research. I.e. I used to always need food before working out. Now I can wake up and work out, no issues, then have my first meal at lunch. I have even worked out during a 24 hr fast. Working out during a 4 day fast is difficult on day 3, so in the past I took it easy for day 3 and 4 by just taking walks.