Capturing physiological stress using heart rate variability (HRV)

A short case study to discuss measurement time, body position, delayed responses and more

I recently shared some of my data showing very good agreement between morning and night measurements of heart rate variability (you can see it here). There are of course differences, typically due to stressors timing and how night data tends to be tightly coupled with whatever you did in the evening (see for example this blog where I discuss a simple example with late meals and irrelevant night HRV suppressions), but my data tends to be aligned between these two protocols, on many occasions.

Following up on my data, Andrew Flatt showed how in his experience night data hardly ever changes, while morning data is a better representation of his stress response (see his data here).

Published literature looking at these differences reports (full paper here):

“It could be argued that the morning .. being further away from previous stressors and closer to the following, would provide more relevant information on the current state of homeostasis”

“Furthermore, it can be speculated that nocturnal recordings would rather reflect the physiological and psychological load of the previous day than the actual state of recovery and readiness to perform on the following day”

Below I cover not only stressor timing but also - and most importantly - body position, which is the main reason why we recommend a morning measurement. These are important aspects, as the data is used in similar ways, but it does not necessarily capture the same responses.

Despite my own experience showing a good agreement between morning and night measurements, I understand Andrew’s view and would argue that the following generalizations are often applicable:

night data: an overall health marker, more stable over time (outside of very large stressors such as sickness or excessive alcohol intake), and somewhat less responsive to acute physical and psychological stressors.

morning data: a more responsive indicator of acute and chronic stressors, especially when taken while sitting or standing up (orthostatic stressor). Possibly less coupled to overall health when taken in isolation.

Last week I traveled to Oulu to meet the team at Oura, and experienced something similar to what Andrew reports. Here I want to show the data, but also discuss some of the implications.

Case study

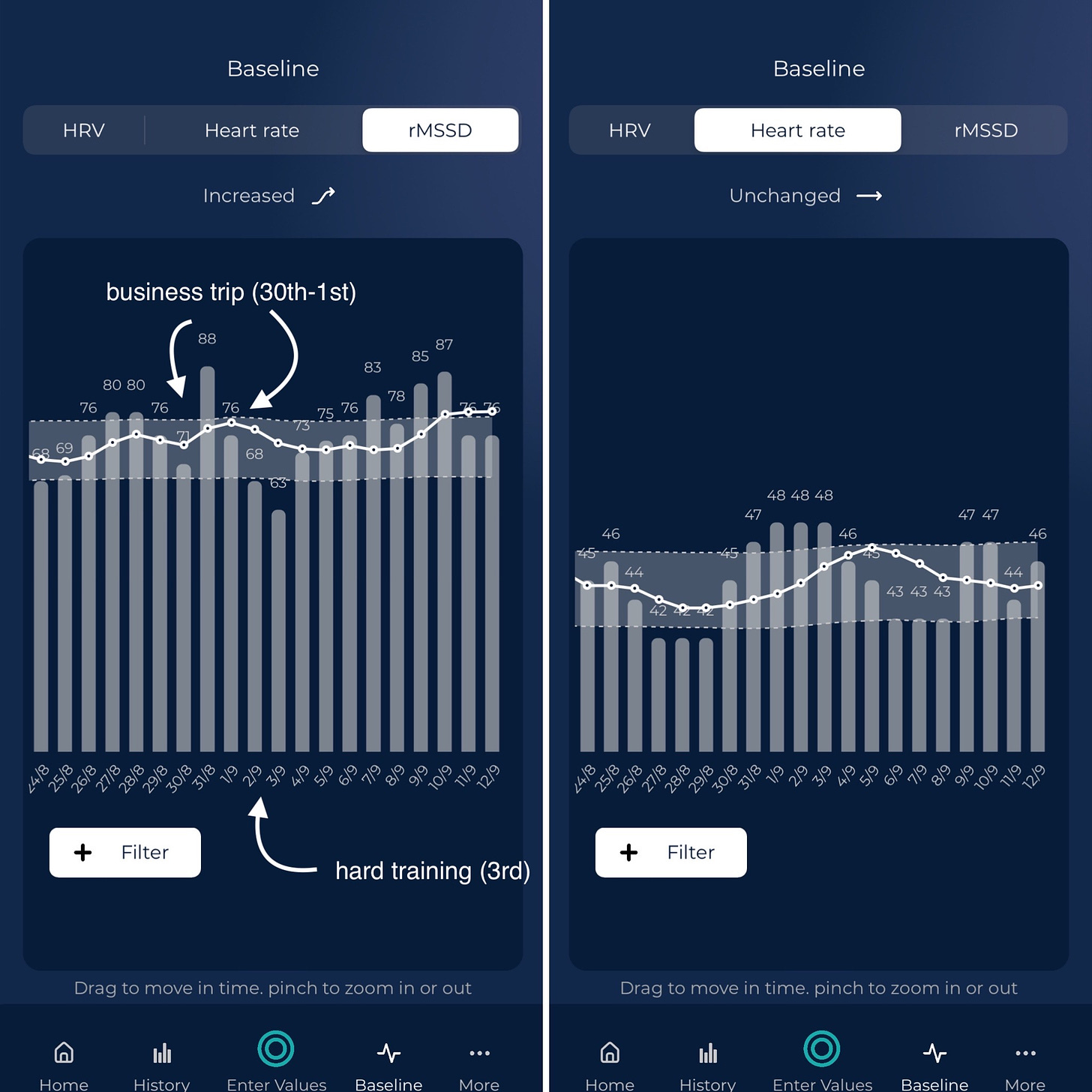

Below you can see my morning HRV data for a few days and stressors.

When I went to Oulu on August 30th I woke up very early to do a hard session on Zwift, then I did a strength session, went to the airport, got to Helsinki from Amsterdam, worked at the airport in Helsinki, and then finally got to Oulu. Once in Oulu, I went for a late run. I slept quite terribly in the hotel and woke up again very early to go for another run before a day of meetings. The following night I slept again poorly, then ran early in the morning, spent the whole day working in airports, and ran again for two hours when I got back home in Amsterdam.

During this whole period, my HRV was very good, high end of the normal range, despite me feeling definitely tired and off with the weird schedule I am not used to anymore.

Both morning and night data showed the same for these days, high HRV, which was quite decoupled from my subjective feeling due to lack of sleep, traveling, working out at early or late hours, etc.

Once I got home, I was expecting the data to get even better or stay stable, but the opposite happened. Maybe I had some “buffering capacity” for stress, which was also reflected by the previous months of stability and relatively high HRV (top end of the normal range most of the time), but then suddenly fatigue really caught up with me, even though with different timing.

On Sunday I went for a hard workout on a low HRV day, thinking it was nothing and it would bounce back quickly. Despite feeling better, sleeping in my bed, training when I wanted to train, and resting, my HRV started reducing and stayed suppressed for several days.

At this point the data was predictive of what was about to happen: Monday to Thursday I felt quite terrible and trained poorly. I had to cancel any intensity, I just didn’t have it in me. The data reflected my state, even though I didn’t notice it at the beginning.

None of this was visible in my night data:

I have two points that I want to bring up here that I think are of interest:

morning measurements can be more sensitive to stressors, as highlighted by Andrew Flatt several times. This might be due to the orthostatic stressor, hence I do not expect to see the same if I am measuring while lying down, even though being awake is already different from being asleep (and therefore there might still be something to gain even when measuring in that body position, since you are not as parasympathetic as when asleep). Challenging the body allows us to see things that we cannot see in a state of complete rest. Think about the difference between your night glucose and a glucose tolerance test (i.e. ingesting glucose and seeing how your body responds provides additional information that is not visible in your resting glucose level). Similarly, your night HRV shows your state when at full rest, but challenging the body’s homeostasis by simply sitting up, which requires the body to quickly re-adjust, allows you to capture your stress response in ways that are otherwise not possible.

the impact of stress on our data and feel is not obvious. I had no change in HRV when I felt really fatigued during the trip. As I said above, maybe I was in a situation in which I could buffer stress better. However, later on, when I actually felt better, I trained hard and caused a negative response, with HRV suppressed for several days, eventually resulting in feeling and performing very poorly. In this case, HRV was somewhat predictive of what was going to happen.

With these points, I want to highlight the complexity of what we are trying to assess, and even more, the complexity of performing interventions or adjusting behavior based on the data.

Maybe I could have avoided the drop by training less during the trip. Or maybe it would have been sufficient to avoid a hard session on the day I had a suppressed HRV after the trip. Or maybe none of these things would have made a change.

We cannot know, but I am quite fascinated by these changes in resting physiology, the timing or delayed response with respect to the stressors, and how they can decouple from a perceived feeling of fatigue or tiredness, sometimes providing early warnings.

Let’s keep learning.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Twitter: @altini_marco.

Personal Substack.

Did you check for any increase in CoV (morning data?) that might have coincided with feeling off?