Last week I came across an article in the Wall Street Journal highlighting how wearables are potentially driving individuals to obsessive behaviors and what I would consider an unhealthy and misguided relationship with tracking.

Here are some bits:

and again:

As someone building tools that allow individuals to track a number of parameters, either subjectively (via questionnaires) or objectively (via measurements of resting physiology), I often think about the implications, and how to do this in a way that allows us to keep track of potentially important parameters, without falling into the dysfunctional behaviors highlighted by the article above.

How do we do better?

Below are some of the choices I made when building HRV4Training, in an attempt to take a step in the right direction in the context of developing a healthier relationship with what can be useful indicators.

No scoring of behavior

Readiness, recovery, and sleep scores are one of the main selling points of wearables. And yet I would argue that there is really no place for them.

I think there is quite a clear difference between monitoring physiology and making up scores that rely on algorithms making assumptions about what good behavior is.

I often have perfectly normal physiology after behavior that would be easily labeled as negative (e.g. shorter or interrupted sleep, high levels of activity, eating dinner a bit later or eating a bit more for dinner, etc.).

The body's ability to cope and perform under stress is not captured by scores that include behavior in the predictors (sleep, recovery, readiness, etc.).

Additionally, these scores mix behavior and physiology, making it harder to understand if your body has actually been impacted negatively (i.e. your physiology is abnormal) or if your behavior has simply been different.

If there is such a strong link between your behavior and your score that you know already that an imperfect night will lead to a lower score (to the point that you take off your wearable on those nights, as described in the article above), then what are you wearing the sensor for?

You already know what it will tell you. If we focus on the physiology instead of these made-up scores, the situation differs. You might in fact be in a perfectly normal state after a suboptimal night.

This reasoning is why in the past decade we have always resisted the urge to build such aggregated scores, despite what everyone else is doing. No need for any of these scores, in my opinion.

Reporting actual physiological measures with their normal ranges

What do we do if we do not build made-up scores combining behavior and physiology?

In my opinion, it is a lot more useful to look at the actual physiology, and in particular at physiological parameters that your wearable can measure, not the ones that it can only estimate (please see this blog for a deeper analysis of these important differences between the metrics reported by wearables).

Parameters that are measured by wearables are normally very few, e.g. your pulse rate, pulse rate variability, and maybe skin temperature.

Once we have isolated the few parameters that matter, how do we use them?

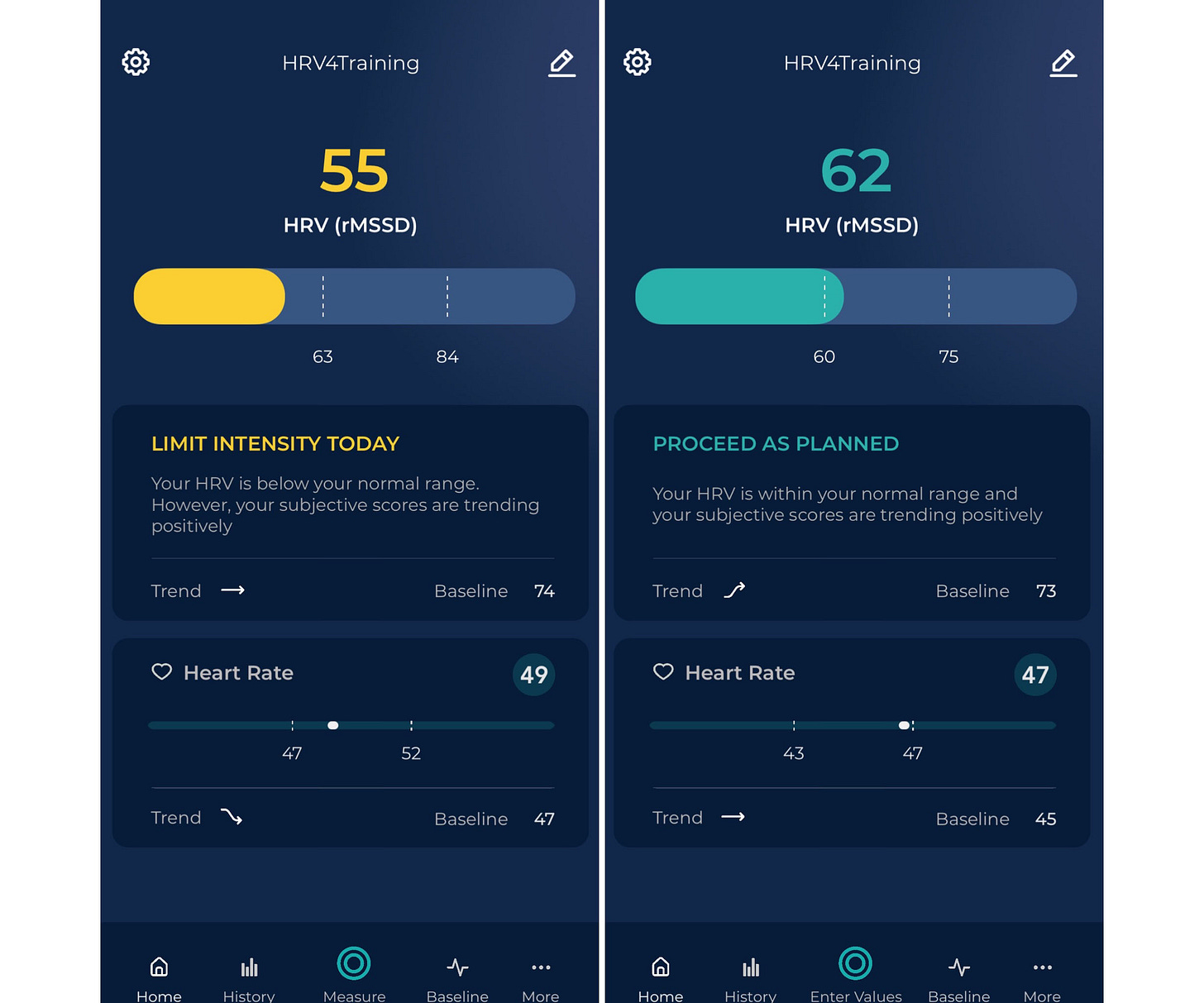

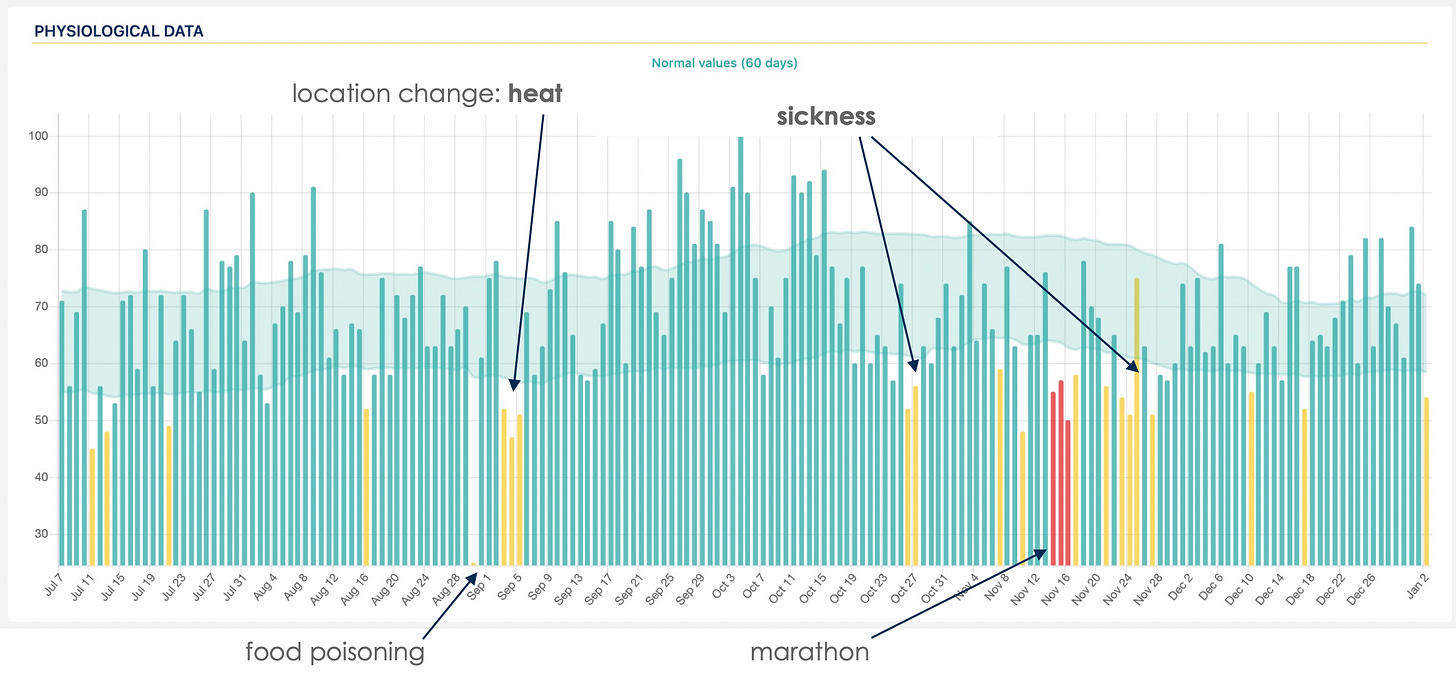

It is perfectly normal to compare numbers, but there are ways to mitigate unhelpful / useless comparisons. For example, highlighting how a certain parameter is within your normal range on a given day allows you to understand that even if it is e.g. a bit lower than yesterday, this variation is of no physiological and practical meaning.

Wearables manufacturers might want to “engage” you with their platform, to the point that they now give you all sorts of not-very-useful real-time metrics (a prime example here is how meaningless HRV can be when measured continuously, as I discuss here), and fail to provide you with a clear representation of what a parameter is outside of what is your normal range. Check out this blog to see how we build your normal range in HRV4Training, to easily identify meaningful changes in your daily physiological values or weekly baselines.

Most of the time things are “just normal”. This means that on most days, there should be no (re)action, and following your plan should be the preferred choice.

Annotating subjective feel

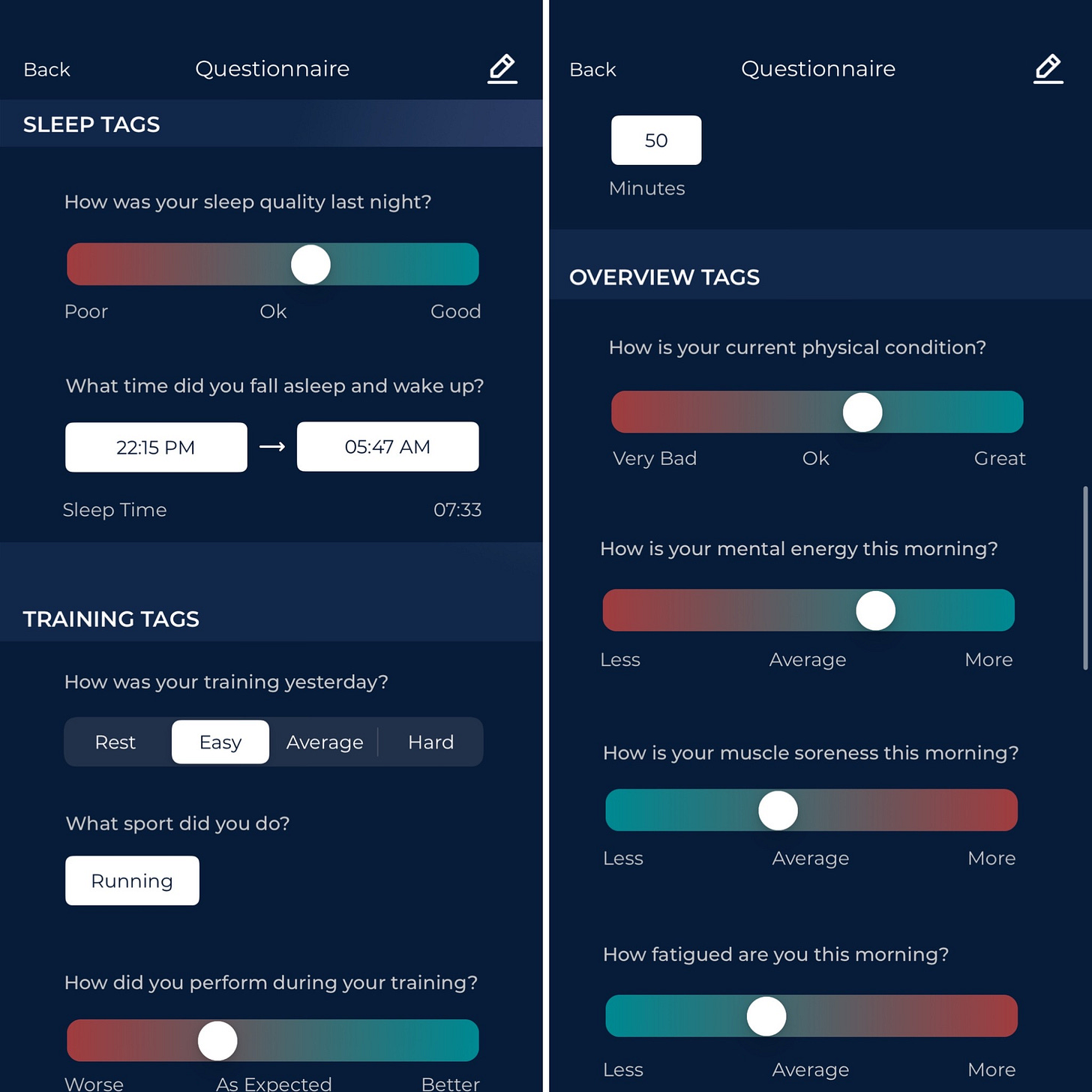

Another aspect that I think is key and is often ignored by wearables, is reporting how you feel, in particular before you look at your metrics.

Reporting how you feel obviously requires you to do some work, which is why wearables ignore this aspect: the user cannot possibly be bothered with spending a few seconds using their brain, and the wearable always knows more / better.

I see this quite differently, reporting how you feel subjectively before you look at your metrics, as part of a simple questionnaire, allows you to stop and practice a little exercise in interception. This exercise will get you in tune with your body and will put metrics in perspective.

The goal should not be for you not to think about how you feel and to be instructed on your behavior (what wearables end up doing), but the goal should be to get more in tune with your body and possibly make some small adjustments in behavior.

The wearable has no context, often captures inaccurate or partial data, etc.

I will stress this with one more example: some wearables can be charged while you wear them. This is to push the rhetoric that you have to wear them all the time and that they will be able to capture “so much data” and give you this great understanding of your body. This is a myth.

Now let’s remember that most of these sensors are built for athletes. What is the greatest limiter for athletes most of the time? That’s muscle soreness.

Is any wearable able to capture muscle soreness? No.

If anything, this simple realization should allow you to take the whole rhetoric a little less seriously and become more intentional with your tracking. In fact, a single morning measurement taken following a specific protocol (e.g. an orthostatic test) can be more informative than wearing a sensor 24/7 (learn more here).

Alright, I hope this clarifies some of the choices I made when building HRV4Training, and how I hope they can make it easier to develop a better relationship with tracking metrics that can otherwise be useful in a number of contexts, from health to performance.

Thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Nice article.

I did look at my sleep data a few years back when I had a Polar and noticed a drop in quality when drinking alcohol. We all know the impact of alcohol on our body and recovery, but visually seeing the impact (also with HRV) did make me stop drinking completely, with all positive results linked to it.

So perhaps as with everything, it's key to be aware but not to obsess over it.

In regard to the HRV app, what is the impact of sliders like sleep quality? Purely the advice?

And how to use the sliders? Should you use them as a all out or nothing? Because I only gradually move them as I never exaggerate scoring.

Great article, thanks! I'll be sharing this when discussing the shortcomings of wearable's scoring.