Should Heart Rate Variability (HRV) be negatively correlated with training load?

no, the answer is no

It is a common misconception that HRV should track training load, for example reducing when training load is higher (resulting in a negative correlation between HRV and training load).

Studies looking at the relationship between HRV (and other metrics) with training load over time, often look at how these metrics correlate. However, there are at least two issues with this approach:

The whole assumption that you should find the metric that “correlates the most” with training load, makes very little sense. You already know the load, you want to know the response.

HRV is all about individual responses. An ideal response to high training load (intensity and or volume) is a stable HRV, with a quicker rebound for more fit individuals, as I discussed here. Only in case of issues, a reduction will be present. Hence HRV should not simply result in the opposite trend as what we see in training load.

Correlation between training load and other metrics

Why does it make little sense to judge a metric based on its correlation with training load? Because you are already measuring training load.

What is the point of having another metric that gives you the exact same information? By definition, if a metric is perfectly correlated to training load (positively or negatively), then it is a useless metric because it does not add any information.

For example, if HRV had a perfectly negative correlation with training load, It would not add any information to the training and recovery equation. Ironically, these studies interpret the metric with the highest negative correlation with training load as the best metric, failing to understand what HRV is about (i.e. the response! - at least when measured at the right time).

Are you interested in your body’s response, or are you interested in tracking load? They are both informative, and they are not the same thing nor they should be correlated in any trivial way. Unfortunately, sports science studies are often trivial and unable to capture the complexities of long-term changes happening in real life.

Individual responses

On top of this, HRV is all about individual responses. A non-relationship at the group level does not tell us anything at the individual level. Maybe a few people responded very well and had increased HRV. Other people had a suppression in response to the same load, others had non-training-related stressors playing a role. This is exactly why we monitor.

It makes sense to analyze group-level data in response to acute stressors (see for example our paper here where we look at training, sickness, alcohol intake and the menstrual cycle). However, in the long run, acute and chronic responses differ. As such, a group-level analysis does not tell us anything about the individual response, nor the within-individual correlation over time does.

The notion that increased load should trigger a reduction in HRV is very simplistic. We can have stable or increased HRV when increasing load (a sign of positive adaptation) and decreased HRV with reduced load because of other stressors (travel, work). See a simple case study here.

Here is my data for the past 3 months, showing both load and HRV:

We can see that both HRV and training load increase a bit, possibly coincidentally (I ran a marathon on November 13th, hence load was reduced a bit that week and the two weeks after, also, I was sick both before and after the marathon, plus the race was hard, hence the HRV dip which then re-normalized). Overall, we either have two stable lines (in the past 2 months) or a positive correlation (both HRV and load looking good or slightly increasing: a sign of things progressing well).

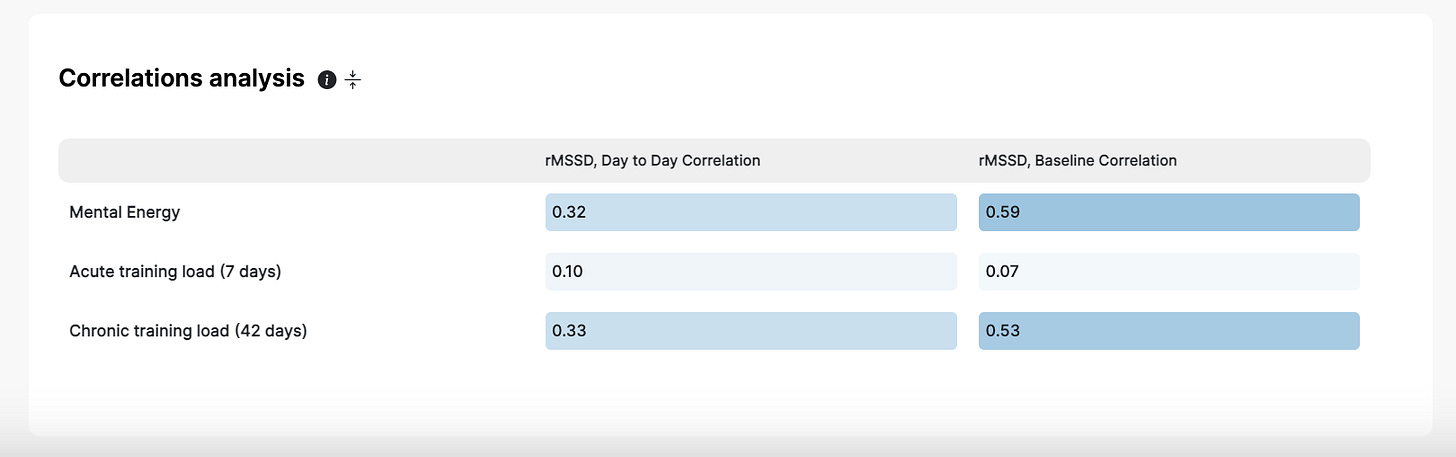

Here is another screenshot from the new HRV4Training Pro (you can try it here), which will report correlations between all selected parameters on the Overview page.

Get it? No analysis of these two variables without context provides any meaning, nor we should expect any association in either direction.

How should we use HRV and training load then?

If our training load is increasing and our HRV stays within normal or increases, that’s great, it means we are responding well to stress. This is confirmation that we can take the load, maybe even increase it a little more. This is what we normally see in elite athletes or when the load is appropriate to the current fitness level of the athlete. If on the other hand we have a suppression in HRV, measured the following morning, it means we were unable to bounce back from the stressor in a reasonable time, and most likey have overdone it (or there are other non-training-related stressors present). Either way, we can then modulate training (reduce intensity of the following sessions) or give priority to recovery strategies (e.g. an extra nap).

In general, HRV should not negatively correlate with training load. By measuring your resting physiology first thing in the morning, you can understand how you are responding to training (and other stressors), and use that information as part of your decision-making process.

I hope this was informative, and thank you for reading!

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social: