One of the common mistakes you see when using HRV to generate advice is how “good HRV values” are often used to generate messages about going hard or doing more.

There’s actually even an additional issue here to discuss first, which is the definition of what a “good HRV value is”. Many wearables and apps still use a simplistic “higher is better” approach (see also this blog where I discuss abnormally high HRV values). However, a good HRV is a stable value, typically within or near your normal range (if your tool of choice doesn’t show you your normal range, you can input your data in HRV4Training to get a better understanding of your physiology).

Now that we have defined what a good HRV is, we can move on and interpret it. Normally, a good HRV means that you have responded well to the various stressors you are facing, training included.

And yet you see apps and wearables using HRV to generate advice and messages about going hard or doing more when you have a high HRV.

This is not how physiology works, and especially for athletes, it makes no sense.

Why?

While having a good response to training and other stressors (i.e. a good HRV) is great and informative, other aspects, some of them limiting our ability to perform more than anything else (i.e. muscular damage / soreness), are not captured by this data.

This is why HRV can only be used to adjust a plan, not to define one.

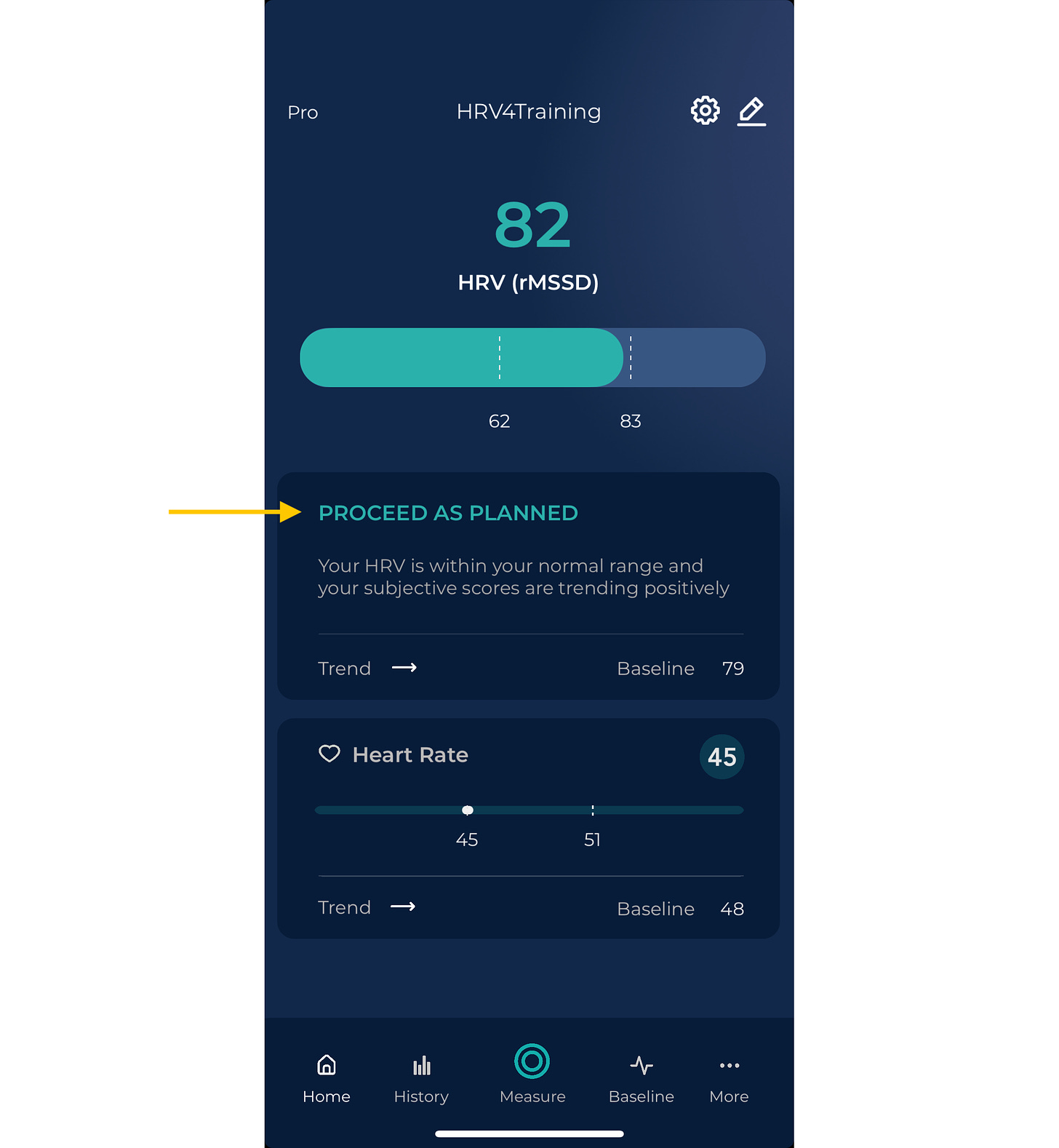

The most appropriate thing we can say when HRV looks good is to proceed as planned, because you do need a plan, which might include easy and hard days.

If your HRV is good after a hard day, it means you are responding well to your training, not that you should be doing another hard session. If your plan was a rest day, take that rest day.

Ideally, you always want to see your HRV, or at least your weekly average HRV, within your normal range. It shouldn’t drop unless you are 1) responding poorly to training 2) experiencing non-training-related stressors. A good HRV does not mean that you are not experiencing stressors: it means you are responding well to stressors. Similarly, a suppressed HRV does not mean that “you did a big workout” (congrats), but it means that there was a mismatch between the work done and your ability to tolerate it (and to improve / adapt).

Don't get fooled by readiness or recovery scores and messages, there is no way these can capture your ability to perform on any given day. Wearables often trivialize physiology.

Use tools that interpret HRV within the limitations of what it can or cannot do.

How can we build a more useful combined score?

All of the above is not to say that combined scores cannot be helpful, but they simply cannot be automated.

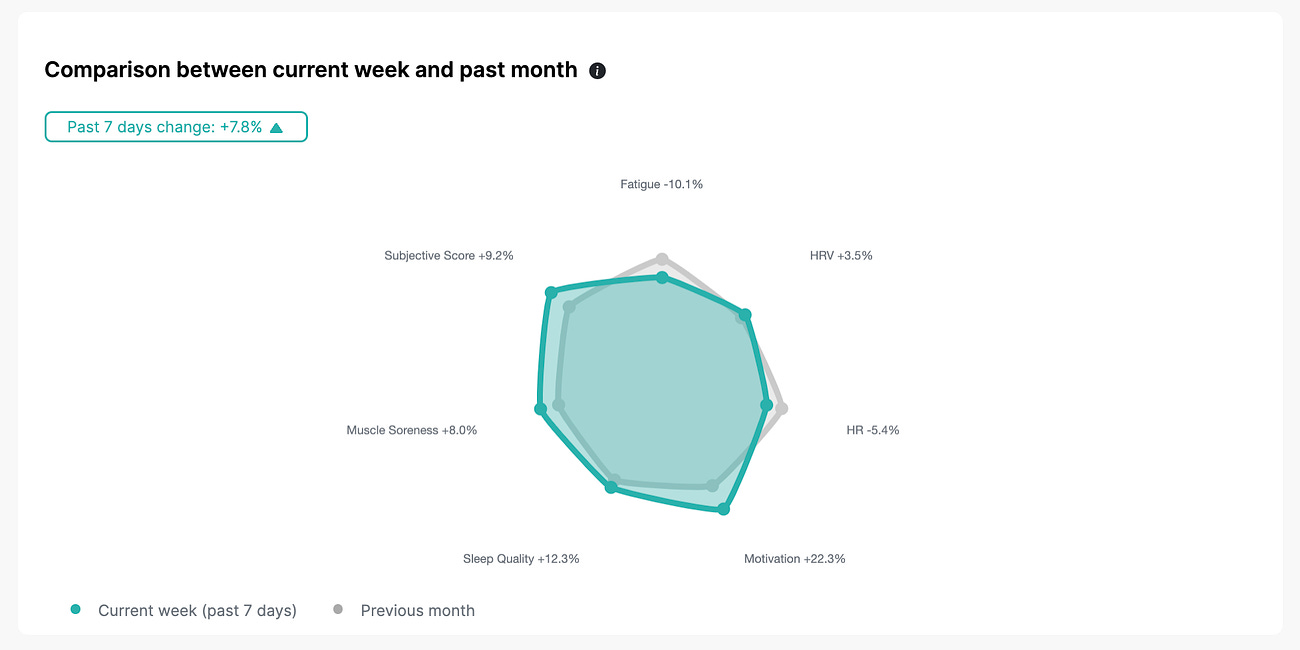

If we want to build a combined score, together with your physiological response (resting heart rate and HRV), we need to add subjective data that only you can enter. For example, muscle soreness, or fatigue, or other parameters that are relevant specifically for you. These are typically outputs, not inputs (e.g. behaviors), just like HRV is an output.

Check out the Dashboard page in HRV4Training Pro to build your own custom score.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Twitter: @altini_marco.

Personal Substack.