Wearables these days provide lots of metrics. As a result, it is often confusing for users to determine which ones to pay attention to, and which ones are probably not worth our time.

In this blog, I’ll cover the main differences between actual physiological measurements (e.g. your resting heart rate and resting HRV), and made up scores (e.g. readiness or recovery scores).

When you use a wearable, presumably to measure your body's response to what you are doing (stressors), you have two options:

1) Looking at the physiology. For example your resting heart rate, pulse rate variability, temperature, etc. That's how your body responded.

2) Using a made-up score that includes your behavior and as such, becomes some sort of self-fulfilling prophecy.

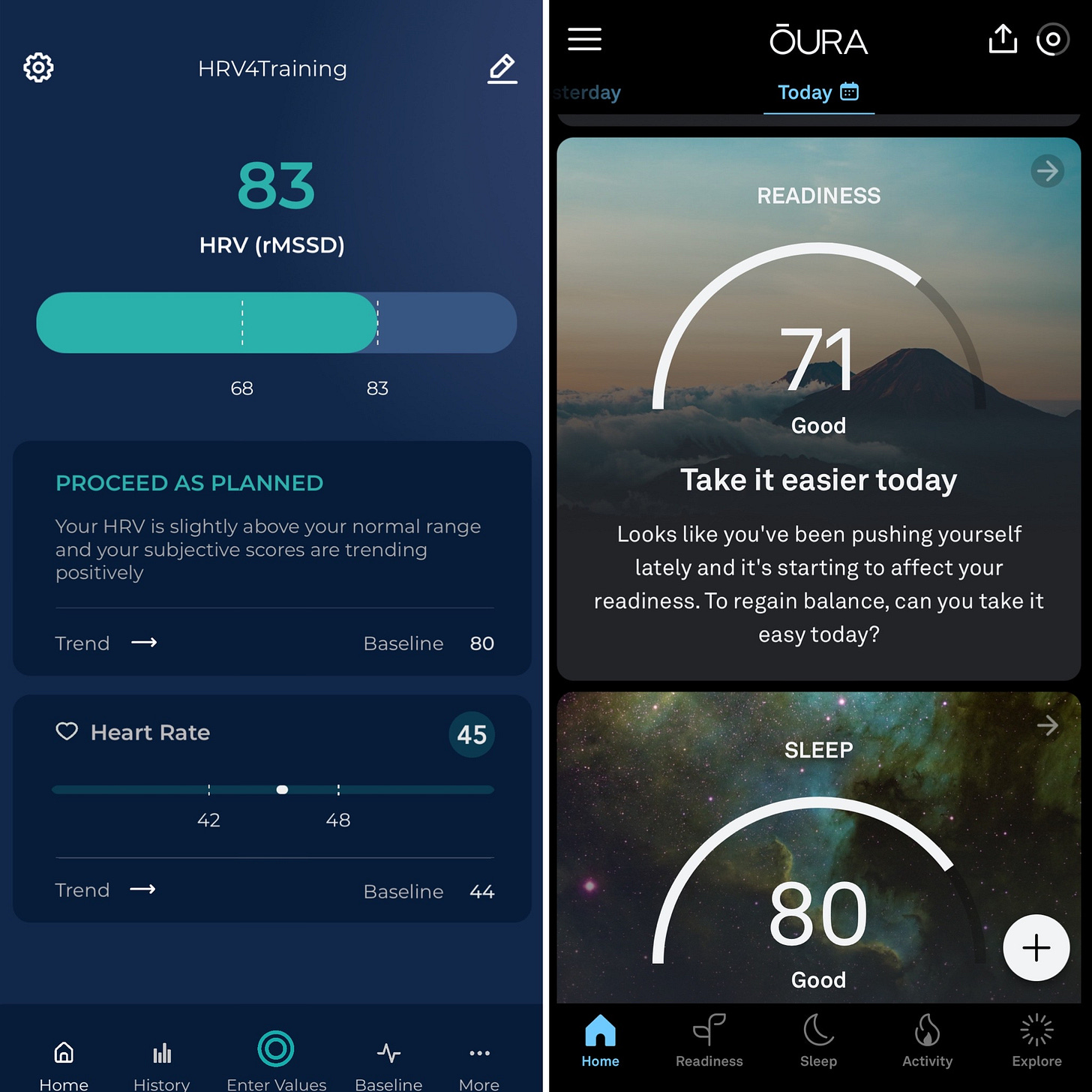

Check out the simple example below: I was more active and I slept a bit less, my readiness must be low (behavior, not physiology, results in a low score, as the algorithm makes assumptions about how we should be responding to a certain behavior, despite the fact that of course, we might not be responding that way).

However, my physiology is in fact showing a very good response, on the top end of my normal range (see the left side screenshot, from HRV4Training).

Here the same data has been used. It is not a matter of measuring different things, it is how that information is used. I've read in HRV4Training my HRV from Oura, which was 83 ms in rMSSD.

Wearables can be informative if we use them to look at what our body is saying, as opposed to what an algorithm thinks we should be feeling based on our behavior.

What does the research say?

In a recent study brought to my attention by Sian Allen on twitter, researchers looked at self-reported stress measures (collected via a validated questionnaire), in relation to physiological measurements (e.g. resting heart rate and HRV) and made-up scores (the recovery score provided by a wearable).

As expected, we had a negative correlation between self-reported stress measures and HRV, i.e. the higher the stress, the lower the HRV. Similarly, we had a positive correlation between resting heart rate and HRV, hence the higher the stress, the higher the resting heart rate. The relationship between HRV and stress was also somewhat stronger than the relationship between heart rate and stress, highlighting once again how HRV is probably a more sensitive marker of stress. So far so good.

How about the recovery score? There was zero correlation between the recovery score and all other variables. This is quite something, I am not sure I’d be able to design a score that ends up being as useless as this one, even if I wanted to.

Please do yourself a favor: if you want to use a wearable, at least use it to look at the physiology, and ignore made-up metrics (recovery, readiness, etc.).

I discuss in more detail measurements and estimates in my blog below.

A framework to make better use of Wearables data

When it comes to wearables, I often see either blindly embracing a device (i.e. fanboy kind of attitude, or sponsored athlete), or dismissing it entirely because of e.g. an inaccuracy in a metric provided (e.g. skeptical coach or scientist). Unfortunately,

Thank you for reading.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching.

He has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Twitter: @altini_marco.

Personal Substack.