[CoachCorner] Why Perceived Effort Should Guide Your Training

Ode to the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

One of the most common questions I get as a coach is: “Should I train by pace, heart rate, or power?”

Sometimes this comes as a demand more than a question, but my answer is almost always the same: none of the above.

In this blog I’d like to make the case for the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) (which I will also simply call perceived effort), as the most powerful and sustainable way to guide training long term.

In particular, below, I’ll cover why RPE is the most robust tool we have, why external load or objective internal load metrics often fail us, and how trail running teaches us lessons we can bring into any type of training.

And of course, we’ll also look at exceptions and situations in which heart rate and pace do bring value and should be used to guide training (or racing!).

What is RPE?

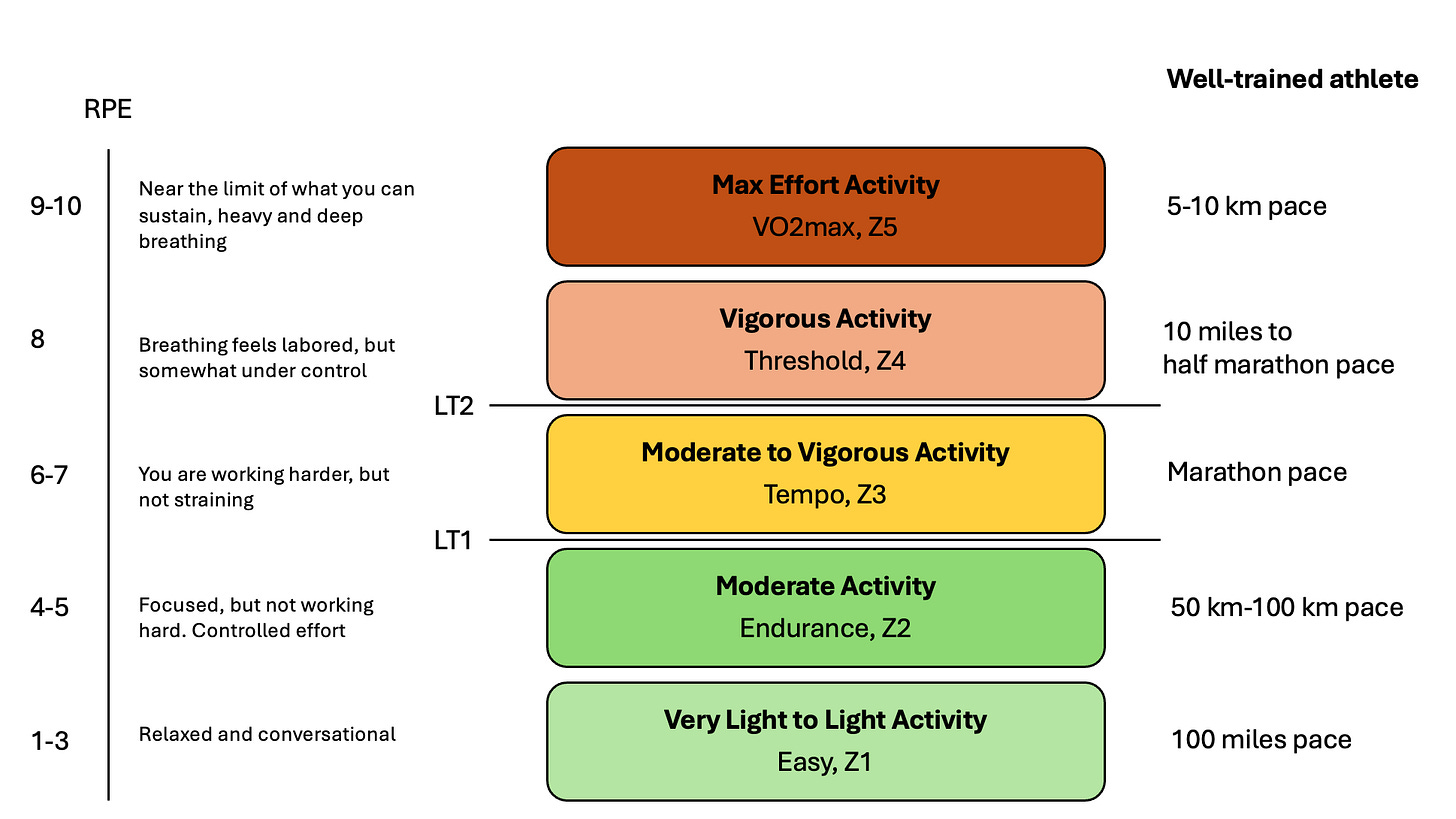

Let’s start with the basics. RPE is simply how hard the effort feels.

It’s your body’s internal sense of effort. Easy runs feel easy, threshold efforts feel controlled but demanding, and maximal sprints feel all-out.

This scale, while subjective, has been validated across decades of research. It correlates strongly with oxygen consumption, lactate accumulation, and heart rate. But more importantly, RPE helps us avoid limitations associated with using external load (i.e., pace or power) or objective internal load (heart rate) metrics to prescribe training. Limitations that we’ll see in more detail in the next section.

Why RPE works when other metrics fail

In training we often distinguish between external load (i.e. the work done, measured for example as pace or power), and internal load, the body’s response to that work, captured by heart rate, lactate, or perceived effort. Below I look at limitations of external load metrics as well as limitations of objective internal load metrics that we commonly use.

External load metrics: no context

External load is easy to quantify but blind to context: a certain pace or power in cool weather is not the same as that same pace or power in the heat, or on tired legs.

It follows that it should be quite easy to understand why external load provides poor training guidance: environmental conditions (heat, humidity, altitude), our previous training (soreness, fatigue, etc.), and pretty much anything else (sleep, nutrition, etc.), makes it so that the way a certain pace or power feels a given day of the week is dramatically different from how it feels the previous or following day. It would be meaningless to plan training following pace or power, without accounting for all of the factors above (and many more) as power or pace zones can easily lead to a mismatch between the prescribed training and the effort required to execute it. Many of the athletes I coach have busy lives (who doesn’t?). They travel, spend time in different environments, have work and family commitments, etc. - and as a result, very similar sessions turn out with dramatically different external loads, despite feeling the same on that given day. Using perceived effort allows us to train well under most circumstances, while using pace or power would set us up for constant failure due to the lack of context.

Additionally, setting a pace or power for a workout beforehand, prevents us from understanding what we are really capable of. We already decided before the session what pace to hit. If we are approaching a new type of session or progressing quickly with training over a few weeks, we might be quite far off in our estimate of our abilities for a given session, and therefore go out too hard (and blow up) or too easy (and get a suboptimal training stimulus). This is a classic I see all the time; i.e., training (or racing) for the fitness we wish we had, as opposed to the fitness we currently have, leading to interrupted workouts, drops in pace, and the typical outcomes we all know.

There’s also something to say about the dangers of constant comparison of external load over sessions (are we going faster today with respect to 4 days ago or last week?). This is a common mindset that however can also only end up in failure. Progressing in endurance training is multifactorial and we might be getting better from a number of points of view regardless of what pace we can hit in a set of 400s (maybe our running economy has improved, or our ability to tolerate fatigue, or our durability in very long events that we target, etc.). Additionally, racing workouts is also a recipe for disaster, possibly increasing injury risk (and compromising long term consistency of volume and intensity, which is after all, what matters). Targeting paces can lead to constant comparison which eventually compromises long term athletic development. Finally, how long can we realistically keep this up? Getting better every workout is simply not going to happen, hence the quicker we move away from this mindset and embrace “doing the work consistently” the better.

In this context, perceived effort / RPE is once again an ally.

Objective Internal load metrics: partial picture

Internal load should reflect how demanding the work truly is on that day.

However, objective internal load metrics can offer only a partial picture. For example, we can think of heart rate as the most easily measurable parameter to approximate internal load, i.e. an objective internal load metric.

My critique of heart rate here is not the one you will usually find. Often, heart rate is deemed problematic because it changes with temperature, humidity, fatigue, etc. - but that’s in fact a strength in my view, and if it was just about that, I’d certainly think of heart rate as a great parameter for training prescription, as all of those factors impact perceived effort as well. If I want to limit stress on the body or to race a certain distance and my body is working harder (i.e. heart rate is higher because it’s hot), then I better adjust my external load (i.e. run slower), or I won’t get to the end.

However, heart rate doesn’t track effort well in various circumstances. For example, if I am terribly sore because of a hard workout, my heart rate will be low, but running will feel hard and I might need to run even slower. Pushing to stay in a certain heart rate zone, even a low one, would be risky (injury wise) and meaningless (if the goal is easy volume we do not want to accumulate additional fatigue or further delay recovery).

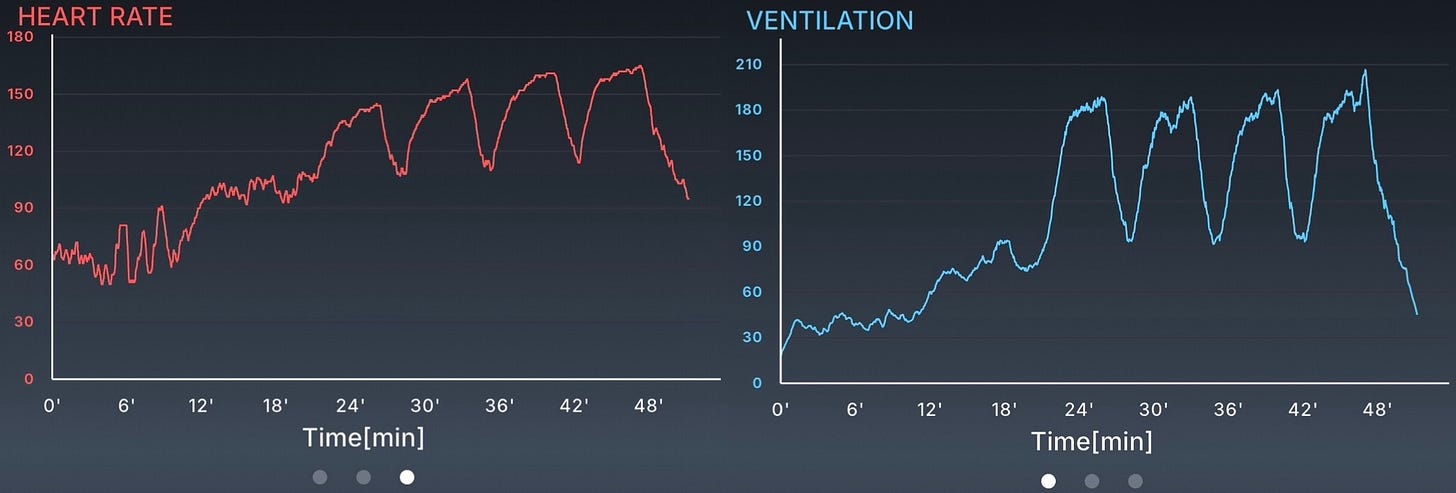

Somewhat similarly, when doing hard intervals, it will take a while before heart rate increases. Are we not working hard in the first few repeats, or is the parameter simply not reflective of the effort? The correct answer is the latter. Metabolically and mechanically we are working hard but it will take a while before we see it in heart rate data, and we might never see it if the effort is short (e.g. when doing hill sprints).

Finally, there will be days in which heart rate is more or less suppressed, in ways that are not easily interpretable, and trying to reach a certain heart rate (e.g. 95% of your maximal heart rate - the maximal value also being something we can’t know for that given day!), will also set us up for failure, since we are likely going to be unable to finish the workout if we are pushing well beyond what is sustainable, while chasing an unattainable (for that day) goal. This is one of the main reasons why I do not think we can effectively prescribe workouts using heart rate (with some exceptions, covered below): the day to day variability is not easily interpretable or explainable on many occasions.

Thus, tracking internal load objectively, while useful at times, offers only a partial picture and RPE remains the most direct measure of internal load, integrating all sources of stress into a single, actionable signal which “just works” every day under most circumstances. The work you put in is always appropriate to your condition and the environment. Sometimes we might be a bit quicker, sometimes we might be a bit slower, sometimes we might surprise ourselves and learn we are capable of more than we thought we’d be capable of.

For people that have a tendency to get too caught up in metrics, focusing on effort can also feel quite liberating, and provide additional benefits in making training a sustainable, long term process. How do you feel about your workout? Does that answer change after you’ve seen your heart rate or pace? Is your assessment of the workout tightly coupled to having achieved a certain result (e.g. pace)? If this is you, the trail running section below might offer some useful pointers.

When Pace/Power and Heart Rate help prescription

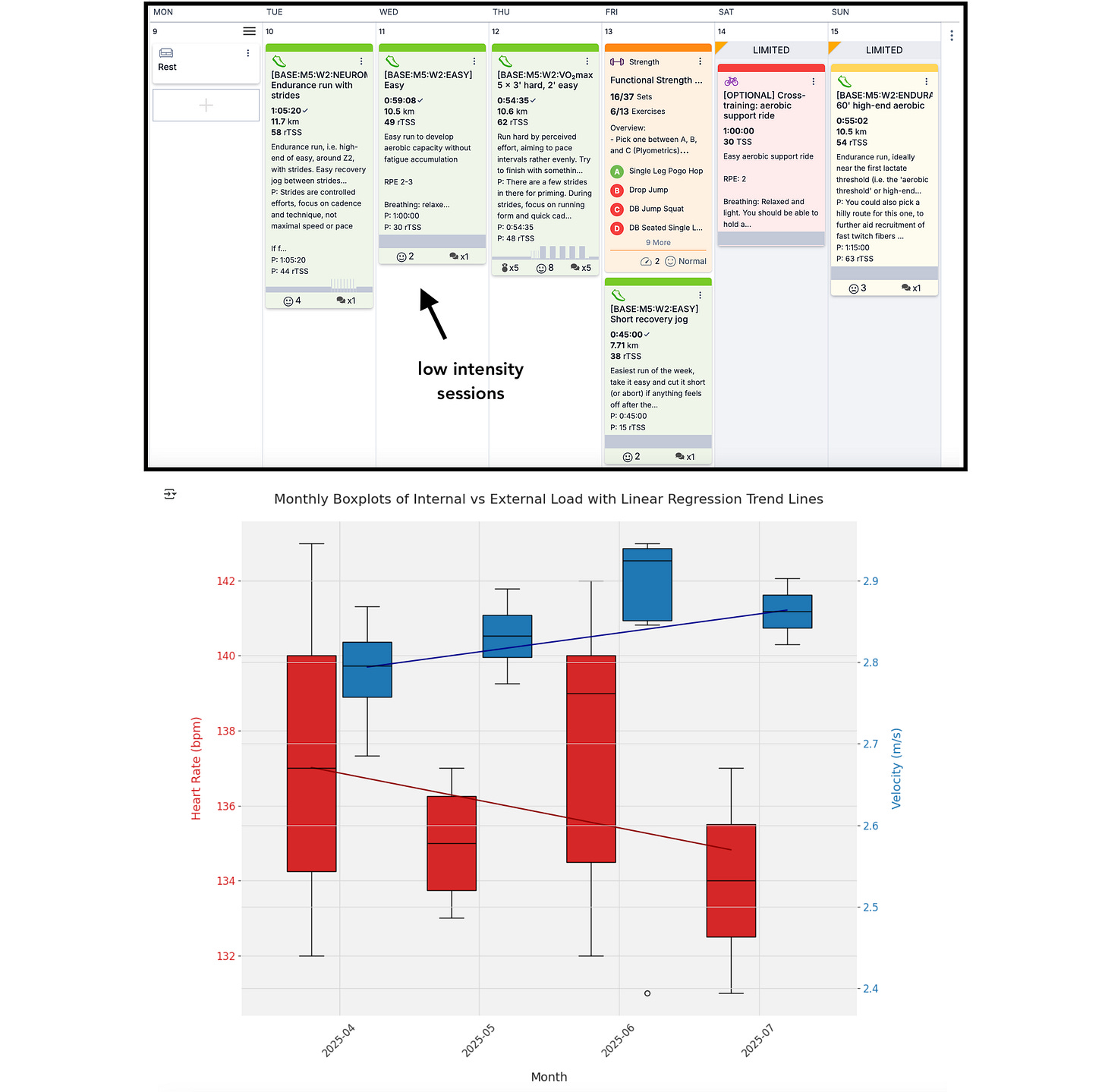

With what discussed so far, I do not mean that external load metrics are irrelevant, quite the opposite. External load is key context for internal load, and in the long term, it helps us contextualizing physiological changes and assess progress. For example, I put together a script to track how internal and external load evolve over time during easy training sessions, for the athletes I personally coach. This is what we could call aerobic efficiency, or the ability to run quicker at a lower heart rate.

Below is the data for a runner I’ve been working with since March, showing great progress in the past months. A simple but effective tool (which you can also find in HRV4Training Pro, as covered here).

Ok, I’ve digressed.

Apart from this “big picture” kind of analysis, there are occasions in which both external load and objective internal load can be very useful also in terms of daily prescription. Let’s get to it.

Pace/power guidance

Using external load for prescription is typically about specificity (and reality checks), which becomes more important as we get close to an event. Say we are preparing a road (or track) race and we aim at racing a certain time. Obviously, we’ll achieve our goal only by hitting a certain pace. As such, we want to practice that pace: we want to learn how it feels, we want to become more efficient at it and we want to understand if our goal is achievable.

To do so, there’s no better way than running at a given pace, and that’s what we will do e.g. for the last training block before a marathon - if possible. The caveat is always there because if we train in different conditions (altitude, temperature, etc.) - we might never be able to use pace this way. This is all about specificity, and less relevant outside of the block prior to a road race.

Heart Rate guidance

I use heart rate a lot. However, I don’t use it for prescription. Heart rate for me is a key cap when facing a certain task. For example, during a marathon or an ultra, I know from experience such as previous races or race simulations that exceeding that cap will result in major drama (cramps or other issues leading to slowing down and not achieving whatever goal I had - something I cover in greater detail here).

However, this is very different from aiming for a certain heart rate (or zone). During a marathon or an ultra I still tune in with my body and feel the intensity. That’s what I try to work towards also with the people I coach. If the effort that feels sustainable for the required distance on that given day results in a heart rate that is quite a bit lower than what we thought it’d be sustainable, we should not make any change. The suppression might be due to the usual number of factors, some of them hardly explainable, and pushing harder would likely lead to disasters (the odds are that our maximal heart rate is also suppressed on that day, hence we are working at the right relative intensity, but we just have no way to see it in heart rate data, which would fool us to think we can work harder). As an example, during my marathon personal best, I was coming from sickness, then an intercontinental flight, and then on race day it was a particularly cold morning, all sorts of factors were playing a role, and my heart rate ended up being quite suppressed. I never thought “I should push harder”, but simply tuned in the effort, which was barely sustainable to the very end, when I started cramping.

This is all to say that a cap is not a target, it’s a red flag we need to watch (and that we can only determine accurately based on training and racing data, not formulas) to prevent issues. This is when heart rate is useful the most, as an integrative measure of stress, especially for long(er) and steady endurance efforts (i.e. not for short repeats). In races in particular, we might get carried away or be overly enthusiastic, so to speak, and a heart rate cap can keep us honest.

I have a cap for a high-end aerobic run (LT1), or for a marathon, or for an ultra, but I never aim for a certain heart rate or zone - I start running, and after a while, I glance at the watch. Is my heart rate higher than what I know I can sustain for a given intensity? Then I try to tune in with effort even more, slow down a bit, watch my breathing, and take it from there.

Somewhat similarly, during an easy run, If I’m running at 110 bpm, I am not doing so because I think I have to keep heart rate that low for whatever reason, but I am doing so because the feel of an easy run on that day results in that heart rate. Maybe soreness that day meant that for a run to feel easy, heart rate had to be that low and pace had to be really slow.

Learning from Trail Running

Trail running makes the irrelevance of external load obvious: pace and power fluctuate wildly with terrain and elevation. Similarly, heart rate is influenced by many factors but does not capture mechanical stress, for example, running downhill is low-heart rate but high muscular load, hence making heart rate a poor signal for guidance or prescription.

Here, the only sensible way to train and race is to use perceived effort. You decide whether you’re climbing sustainably, recovering on a flat, or going down a descent without destroying your quads. Trail running, in this sense, is a masterclass in listening to your body. If you don’t have trails near you, hills might do as well, especially if they can be of different grades, making “objective comparisons” harder, and helping us focusing on perceived effort. I discussed the issue of comparisons briefly above. It’s hard to feel bad about a hard uphill workout because there is no frame of reference but your effort. There is no pace to hit to make you happy about the work done, the work done itself will make you happy.

Personally, one of the reasons I enjoy trail racing is that it forces me to be fully present. There is no watch telling me if I am “on pace.” Instead, I feel the effort, moment by moment. I decide how hard I am willing to go, and I accept the consequences. I might still use heart rate caps (e.g. on a hard steady climb), but the task tends to be a lot more dynamic, and as such, you are constantly re-assessing and using perceived effort as guidance.

Wrap up

Learning to train by RPE is a skill. It requires practice and awareness, an awareness that can often be obtained or aided by objective data (don’t throw away your watch just yet). To me personally, it took a while, and heart rate played an essential role in making me understand that I was working too hard during most of my training.

However, the ultimate goal of heart rate (or any other data) should be to improve self-awareness, not to replace it, which is what often happens if we become overly reliant on data (the same applies to morning measurements of resting physiology!).

Once developed, RPE is the most adaptable and effective way to guide your training - and the only tool that can integrate everything from muscle soreness to environmental changes. I hope that in this blog, I was able to make some good arguments for you to consider relying more on perceived effort during your training or racing.

Thank you for reading!

Related articles:

How to Show Your Support

No paywalls here. All my content is and will remain free.

As a HRV4Training user, the best way to help is to sign up for HRV4Training Pro.

Thank you for supporting my work.

Personal Coaching for Runners

If you are interested in working with me, please learn more here, and join the waiting list by filling in the athlete intake form, here.

Marco holds a PhD cum laude in applied machine learning, a M.Sc. cum laude in computer science engineering, and a M.Sc. cum laude in human movement sciences and high-performance coaching. He is a certified ultrarunning coach.

Marco has published more than 50 papers and patents at the intersection between physiology, health, technology, and human performance.

He is co-founder of HRV4Training, advisor at Oura, guest lecturer at VU Amsterdam, and editor for IEEE Pervasive Computing Magazine. He loves running.

Social:

Personal Substack

Instagram

Very interesting! Apart from where you label a graph "Your lungs know the effort before your heart does", though, you don't really touch on respiration as an internal load metric. I tend to go by this quite a bit, far more than using my heart rate. For example, assessing whether I can breathe comfortably for 4 steps out, 4 steps in, or 5, or whatever, normally gives me something objective which I can tie in with my RPE.

I've been a HRV and, an HRV4 Training user for quite some time and I appreciate you sharing what I would consider to be an "unpopular" view that metrics are not the "only real way to improve performance".

As a multi-discipline cyclist and, I've found as you have that the more variable the terrain ie; downhills, poor traction and technical terrain the less accurate of the sum or work actually done.

It took me many years to realize that your statement that "...any data should add to your self-awareness"...I spent a lot of time a slave to my data to my detriment.

Now, I put my data into it's correct place because how "I feel" is the most important data that I have and, I'm still fine tuning more than 30 years in.

Thanks for a really great post!